About this Issue

Suppose someone asked you to be CEO of Apple (last year’s revenue: $156.5 billion).

After the initial rush - fame! fortune! magazine covers and speeches and travel! - you’d probably feel pretty overwhelmed. Running Apple wouldn’t be easy, and the chances are very good that you just wouldn’t know enough. We know we certainly wouldn’t. If we wanted Apple to succeed, we might think it best to decline the offer.

Now suppose someone asked you to run Medicare (2011 outlays: $565.3 billion).

The scope of the problem is similarly vast. And we similarly wouldn’t know where to begin.

Nor would most others. Indeed, even finding the right person to run Medicare would be a bit of a challenge. Now – can we identify the right person to run the entire federal government (2011 outlays: $3.6 trillion)?

That’s exactly what democracy asks us to do. It’s an awesome responsibility. It’s also one that most voters don’t seem to give much attention. Surveys continuously demonstrate an appalling ignorance on the part of the electorate. Voters commonly can’t identify their representatives, or the branches of government, or their powers, or the rights guaranteed under the Constitution. They can’t find on a map the foreign countries we invade. They imagine government programs that don’t exist and deny the existence of well-publicized and genuine ones. And so on.

Nor is this ignorance at all surprising. The returns on knowledge are, to each individual voter, quite low. Political scientists term the result rational ignorance: it simply doesn’t make sense for most voters to spend their time on these matters.

In this month’s Cato Unbound, George Mason law professor Ilya Somin considers the implications of this troubling phenomenon. He does not reject democracy, as some have done. On the contrary, he embraces it - combined with a redoubled insistence on limited government. His lead essay draws on his new book, Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter.

To discuss with him, we have invited Heather Gerken, the J. Skelly Wright Professor of Law at Yale Law School; Jeffrey Friedman, the editor of Critical Review; and Sean Trende, senior elections analyst for RealClearPolitics.

Lead Essay

Democracy and Political Ignorance

Democracy is supposed to be rule of the people, by the people, and for the people. But in order to rule effectively, the people need political knowledge. If they know little or nothing about government, it becomes difficult to hold political leaders accountable for their performance. Unfortunately, public knowledge about politics is disturbingly low. In addition, the public also often does a poor job of evaluating the political information they do know. This state of affairs has persisted despite rising education levels, increased availability of information thanks to modern technology, and even rising IQ scores. It is mostly the result of rational behavior, not stupidity. Such widespread and persistent political ignorance and irrationality strengthens the case for limiting and decentralizing the power of government.

The Extent of Ignorance

Political ignorance in America is deep and widespread. The current government shutdown fight provides some good examples. Although Obamacare is at the center of that fight and much other recent political controversy, 44% percent of the public do not even realize it is still the law. Some 80 percent, according to a recent Kaiser survey, say they have heard “nothing at all” or “only a little” about the controversial insurance exchanges that are a major part of the law. The shutdown controversy is also just the latest manifestation of a longstanding political struggle over federal spending. But most of the public has very little idea of how federal spending is actually distributed. They greatly underestimate the percentage that goes to entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security, and vastly overestimate that spent on foreign aid. Public ignorance is not limited to information about specific policies. It also extends to the basic structure of government and how it operates. A 2006 survey found that only 42 percent can even name the three branches of the federal government: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. There is also much ignorance and confusion about such matters as which government officials are responsible for which issues. I give many more examples of public ignorance in my book.1

Widespread ignorance is not a new phenomenon. Political knowledge has been at roughly the same low level for decades. But it is striking that knowledge levels have risen very little, if at all, despite rising educational attainment and the increased availability of information through the internet, cable news, and other modern technologies.

Rational Ignorance

Some people react to data like the above by thinking that the voters must be stupid. But political ignorance is actually rational for most of the public, including most smart people. If your only reason to follow politics is to be a better voter, that turns out not be much of a reason at all. That is because there is very little chance that your vote will actually make a difference to the outcome of an election (about 1 in 60 million in a presidential race, for example).2 For most of us, it is rational to devote very little time to learning about politics, and instead focus on other activities that are more interesting or more likely to be useful. As former British Prime Minister Tony Blair puts it, “[t]he single hardest thing for a practising politician to understand is that most people, most of the time, don’t give politics a first thought all day long. Or if they do, it is with a sigh…. before going back to worrying about the kids, the parents, the mortgage, the boss, their friends, their weight, their health, sex and rock ‘n’ roll.”3 Most people don’t precisely calculate the odds that their vote will make a difference. But they probably have an intuitive sense that the chances are very small, and act accordingly.

In the book, I also consider why many rationally ignorant people often still bother to vote.4 The key factor is that voting is a lot cheaper and less time-consuming than studying political issues. For many, it is rational to take the time to vote, but without learning much about the issues at stake.

The Rational Irrationality of Political Fans

There are people who learn political information for reasons other than becoming better voters. Just as sports fans love to follow their favorite teams even if they cannot influence the outcomes of games, so there are also “political fans” who enjoy following political issues and cheering for their favorite candidates, parties, or ideologies.

Unfortunately, much like sports fans, political fans tend to evaluate new information in a highly biased way. They overvalue anything that supports their preexisting views, and to undervalue or ignore new data that cuts against them, even to the extent of misinterpreting simple data that they could easily interpret correctly in other contexts. Moreover, those most interested in politics are also particularly prone to discuss it only with others who agree with their views, and to follow politics only through like-minded media.5

All of this makes little sense if the goal is truth-seeking. A truth-seeker should actively seek out defenders of views opposed to their own. Those are the people most likely to present you arguments and evidence of which you were previously unaware. But such bias makes perfect sense if the goal is not so much truth as enhancing the fan experience. Economist Bryan Caplan calls this approach to information “rational irrationality”: when your purpose is something other than truth-seeking, it is often rational to be highly biased in the way you evaluate new information and also in your selection of information sources.6Unlike Caplan, I contend that widespread political ignorance would be a menace even if voters were always rational in their evaluation of what they know.

The problems of political ignorance and irrationality are accentuated by the enormous size and scope of modern government. In the United States, government spending accounts for close to 40% of GDP, according OECD estimates.7 And that does not include numerous other government policies that function through regulation of the private sector. Even if voters followed political issues more closely than they do, and even if they were more rational in their evaluation of political information, they still could not effectively monitor more than a fraction of the activities of the modern state.

Increasing Knowledge through Education

The most obvious way to overcome political ignorance is by increasing knowledge through education. Unfortunately, political knowledge levels have increased very little over the last fifty to sixty years, even as educational attainment has risen enormously. Rising IQ scores have also failed to increase political knowledge. This suggests that increasing political knowledge through education is a lot harder than it seems.

Perhaps the solution is a better public school curriculum that puts more emphasis on civic education. The difficulty is that governments have very little incentive to ensure that public schools really do adopt curricula that increase knowledge. If the voters effectively monitored education policy and rewarded elected officials for using public schools to increase political knowledge, things might be different. But if the voters were that knowledgeable, we probably wouldn’t have a political ignorance problem to begin with.

Moreover, political leaders and influential interest groups often use public education to indoctrinate students in their own preferred ideology rather than increase knowledge. In both Europe (where it was established in large part to inculcate nationalism) and the United States (where a major objective was indoctrinating Catholic immigrants in true “American” values), indoctrination was one of the major motives for the establishment of public education in the first place.

Even if public schools did begin to do a better job of teaching political knowledge and minimized indoctrination, it is hard to see how students could learn enough to understand and monitor more than a small fraction of the many complex activities of modern government. This is not to say that we shouldn’t try to use education to increase knowledge. Incremental improvements are probably possible. But if history is any guide, they are unlikely to be very large.

Shortcomings of Information Shortcuts

Some scholars argue that voters don’t need to know much about politics and government because they can rely on “information shortcuts” to make good decisions. Information shortcuts are small bits of information that we can use as proxies for larger bodies of knowledge of which we may be ignorant.

In Chapter 4 of my book, I discuss many different types of shortcuts and explain why they are usually not as effective as advocates suggest. Shortcuts can indeed be useful, and political ignorance would be an even more serious problem without them. But they also have serious limitations, and sometimes they make the problem of ignorance worse rather than better. The major flaws are that shortcuts often require preexisting knowledge to use effectively, and many people choose information shortcuts for reasons unrelated to truth-seeking.

Perhaps the most popular shortcut is “retrospective voting”: the idea that voters don’t need to follow the details of policy, but only need to know whether things are going well or badly. If things are looking up, they can reward the incumbents at election time. If not, they can vote the bums out, and the new set of bums will have a strong incentive to adopt better policies, lest they be voted out in turn.

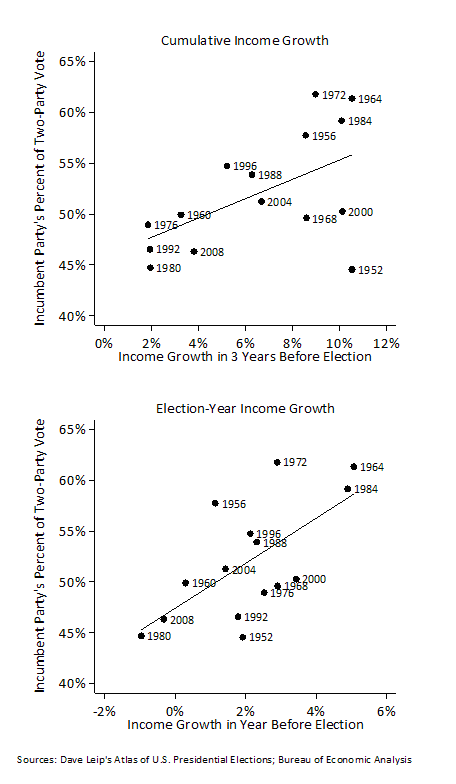

Unfortunately, effective retrospective voting requires more knowledge than we might think. In order to reward or punish incumbents for their performance, it’s important to know what events they actually caused, and which ones were beyond their control. Studies show that voters routinely reward and punish political leaders for events they have little control over, particularly short-term economic trends. Incumbents also get rewarded or blamed for such things as droughts, shark attacks, and victories by local sports teams.

The second common shortcoming of shortcuts is that we often choose them for reasons other than getting at the truth. For example, some argue that “opinion leaders” are useful shortcuts. Instead of learning about government policy themselves, voters can follow the directions of opinion leaders who share similar values but know more than the voters themselves do. Unfortunately, if we look at the most popular opinion leaders, most of them are not people notable for their impressive knowledge of public policy issues. They are people like Rush Limbaugh or Jon Stewart, whose main asset is their skill at entertaining their audience and validating its preexisting biases. Because there is so little incentive to actually seek the truth about political issues, it is often rational for “political fans” to choose their opinion leaders largely based on how entertaining they are, and whether they make us feel good about the views we already hold. When we choose information shortcuts in this way, it increases the likelihood that they will mislead rather than inform.

In the book, I also criticize arguments that voter errors caused by ignorance can cancel each other out through a “miracle of aggregation,” thereby creating collective wisdom out of individual ignorance. Such a happy outcome is theoretically possible, but highly unlikely in the real world.8

Foot Voting vs. Ballot Box Voting

There is no easy solution to the problem of political ignorance. But we can significantly mitigate it by making more of our decisions by “voting with our feet” and fewer at the ballot box. Two types of foot voting have important informational advantages over ballot box voting. The first is when we vote with our feet in the private sector, by choosing which products to buy or which civil society organizations to join. The other is choosing what state or local government to live under in a federal system - a decision often influenced by the quality of those jurisdictions’ public policy.

If you are like most people, you probably spent more time and effort acquiring information the last time you decided which car or TV to buy than the last time you decided who to support for president. Is that because the presidency is less important than your TV, or deals with less complicated issues? More likely, it’s because when people choose a TV, they intuitively realize that the decision is likely to make a difference, whereas ballot box decisions are highly likely not to.

The key difference between foot voting and ballot box voting is that foot voters don’t have the same incentive to be rationally ignorant as ballot box voters do. In fact, they have strong incentives to seek out useful information. They also have much better incentives to objectively evaluate what they do learn. Unlike political fans, foot voters know they will pay a real price if they do a poor job of evaluating the information they get.

That doesn’t mean that foot voters are always well-informed or perfectly unbiased. Far from it. But, on average, they do a much better job than ballot box voters do. In the book, I discuss some dramatic cases of foot voters acquiring and effectively using information even under highly adverse conditions.9 For example, millions of poorly educated and sometimes illiterate African-Americans in the early 20th century Jim Crow South determined that conditions were relatively less oppressive in the North (and also in some parts of the South compared to others) and migrated accordingly. This, despite the fact that southern state governments deliberately tried to keep them ignorant by impeding the flow of information about opportunities in the North. Foot voting certainly did not solve all the problems of oppressed African-Americans in the Jim Crow era. Nothing could in a society as racist as early 20th century America. But it did significantly improve their situation. And it is an important example of how foot voters can effectively acquire and make use of information even under highly unfavorable conditions.

The informational advantages of foot voting over ballot box voting strengthen the case for limiting and decentralizing government. The more decentralized government is, the more issues can be decided through foot voting. It is usually much easier to vote with your feet against a local government than a state government, and much easier to do it against a state than against the federal government.

It is also usually easier to foot vote in the private sector than the public. A given region is likely to have far more private planned communities and other private sector organizations than local governments. Choosing among the former usually requires far less in the way of moving costs than choosing among the latter.

Reducing the size of government could also alleviate the problem of ignorance by making it easier for rationally ignorant voters to monitor its activities. A smaller, less complicated government is easier to keep track of.

Foot voting has downsides as well as upsides. In the book, I cover several standard objections, such as the problem of moving costs, the danger of “races to the bottom,” and the likelihood that political decentralization might harm unpopular racial and ethnic minorities.10 Each of these concerns is sometimes a genuine problem. But I suggest that each is a less severe challenge than commonly believed. For example, moving costs can be reduced by decentralizing to lower levels of government or to the private sector, and such costs are in any case declining thanks to modern technology.

Conclusion

Political ignorance is far from the only factor that must be considered in deciding the appropriate size, scope, and centralization of government. For example, some large-scale issues, such as global warming, are simply too big to be effectively addressed by lower-level governments or private organizations. Democracy and Political Ignorance is not a complete theory of the proper role of government in society. But it does suggest that the problem of political ignorance should lead us to limit and decentralize government more than we would otherwise.

Notes

1 Ilya Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), ch. 1.

2 See Andrew Gelman, Nate Silver, and Aaron Edlin, “What is the Probability that Your Vote Will Make a Difference?” Economic Inquiry 50 (2012): 321-26.

3 Tony Blair, A Journey: My Political Life, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), 70-71.

4 Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 66-72.

5 Ibid., 78-82.

6 Bryan Caplan, The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

7 Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 163.

8 Ibid. 110-17. For an important recent defense of this kind of argument, see Hélène Landemore, Democratic Reason: Politics, Collective Intelligence and the Rule of the Many, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

9 Ibid., ch. 5.

10 Ibid, pp. 144-50.

Response Essays

The Fox and the Hedgehog: How Do We Achieve Political Accountability Given What Voters (Don’t) Know?

Ilya Somin’s new book is one of the most recent and most interesting contributions to the burgeoning work on political ignorance. For a long time, voter ignorance was almost exclusively the province of political scientists. The subject attracted the interest of a few law professors writing about ballot design and the like, but the yeoman’s work was done by social scientists.

While late to the game, legal scholars like Somin have nonetheless made a distinctive contribution in this area during the last few years. Perhaps because they are less constrained by disciplinary bounds, law professors have been more inclined to write broadly about the normative and institutional implications of the empirical research than the political scientists who did the research in the first place. That’s why most of the law professors to work on these questions have ended up looking like a bit like bomb throwers. Evidence of voter ignorance raises tough questions about democracy generally and majority rule in particular. The empirical work casts doubt on whether the majority is capable of forming intelligible preferences, let alone vindicating those preferences through the ballot box.

Law is a problem-oriented field, however, and legal scholars rarely stop with the critique. Somin is no exception. The most novel arguments in his book, in fact, are the ones aimed at solving the problem of voter ignorance. Those arguments pose fundamental questions about what shape our democracy should take.

To get a sense of what’s at stake, it’s useful to juxtapose Somin’s ideas against those of another legal scholar working on the same problem – David Schleicher. Both hail from George Mason (which also houses Bryan Caplan, one of the most prominent social scientists in this area). Somin and Schleicher start with the same empirical research but end up endorsing markedly different visions of democracy: Somin wants us to treat voters as fleet foxes, while Schleicher thinks we should treat them as homebody hedgehogs.

Isaiah Berlin famously categorized thinkers as foxes and hedgehogs. Foxes, Berlin insisted, know lots of little things. Hedgehogs, in contrast, know one big thing. These two categories loosely capture the differences between Somin’s and Schleicher’s reform agendas.

Somin wants us to imagine voters as nimble and detail-oriented as foxes. After canvassing the disturbing number of things voters don’t know, he turns to what they do know: Voters know whether they’d like to live in Portandia or Fort Worth. They know whether they want to live in a neighborhood with good schools, or low taxes, or lax zoning regulations, or mass transit. Voters aren’t just able to make better judgments about these small-scale issues, on Somin’s view. They also have more incentive to acquire information about local conditions (when they move) than they have to acquire information about national policy debates (when they vote).

Somin’s voters are foxes in a second sense. They don’t just know lots of small things, á la Berlin. They are also fleet of foot. Somin argues that voters can and do move based on their preferences. All of this leads Somin to conclude that we should privilege “foot voting” over ballot-box voting.

Schleicher, in sharp contrast, sees voters as hedgehogs. Like Somin, he worries about the many things voters don’t know. But he insists that voters do know one big thing: the basic difference between the two major parties. Like many political scientists, Schleicher believes that party identification – Democrat v. Republican – provides a sensible shorthand for individuals casting a ballot. One group of political scientists explains the significance of the party heuristic in this way: If a voter “knows the big thing about the parties, he does not need to know all the little things.” (Somin doesn’t have the same faith in party heuristics, as is evident from his chapter on the “shortcomings of shorthand”).

For Schleicher, then, accountability depends on voters acting like hedgehogs. Because voters understand the difference between the national parties, Schleicher says we should trust their choices in national elections. He worries, however, that while the party heuristic helps voters hold national politicians accountable, it prevents them from holding state and local officials accountable. When people vote in state and local elections, Schleicher argues, they’re voting based on how they think the national parties have performed, which may not have much to do with local performance. Schleicher’s best evidence is the fact that state and local votes almost always mirror votes on national races. To offer a crude example, Barack Obama’s success in managing the economy doesn’t tell voters whether their mayor is doing a good job with local schools, but the shorthand people use nonetheless leads them to vote in city elections based on their views of Obama. Schleicher’s reform proposals pivot off his belief that voters know one big thing. He is interested in providing voters with a form of party identity that helps them make good decisions at every level of governance.

Schleicher’s argument meets Somin’s in another way. Somin’s fox-like voters move in order to access better policies. Schleicher’s hedgehogs, in contrast, are homebodies. While some may vote with their feet, the inexorable logic of economic need and industry concentration (agglomeration economics, in academic speak) is primarily what draws and holds people to one city or one region. It’s a classic Hirschman tradeoff between exit and voice. Schleicher thinks that exit (voting with one’s feet) is costly given economic realities. He thus wants to facilitate voice by making elections work better. Somin is skeptical that voter preference can be voiced through elections, so he wants us to make exit easier.

Framed this way, you can see how much is at stake in this debate. If Somin is right, we should treat voters as fleet foxes, and the solution to voter ignorance lies with local government law, federalism, and the judiciary. If Schleicher is correct to depict voters as homebody hedgehogs, we should look to politics and election law for solace. Somin wants us to facilitate exit, not voice, and would push us toward tightly bounded microcommunities – enclaves that can develop distinctive policy packages without interference from outsiders. Indeed, Somin doesn’t just want smaller polities, but smaller government. Schleicher’s emphasis on voice over exit suggests we should focus our efforts on large, economically bounded political communities, where there are enough political and media resources for local political identities to develop. His paradigm is New York City. There people seeking jobs in finance or the arts find themselves stuck with high taxes and a history of bad management, but politicians have the political resources to rebrand themselves as “Giuliani Republicans” or “Bloomberg Independents.”

Our choices, then, don’t just involve empirical judgments about what makes voters tick, but deep normative questions about what kind of democratic communities we want to encourage. Thanks to Somin’s vigorously argued and clearly articulated proposals, we now have a clear sense of the choices before us and, more importantly, a better understanding of why those choices matter.

Don’t Voters Get Things Right?

It’s tempting to begin by listing the many things that I liked about Ilya Somin’s Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter. But that could easily take up all of my allotted space and wouldn’t make for a particularly interesting back-and-forth. Nevertheless, I do wish to state up front that Ilya’s book is well worth reading for anyone interested in the problem of how a democracy can cope with an electorate that isn’t particularly interested in politics. It’s lucid, original, and in many ways compelling.

Ilya’s basic argument, at least as I interpret it, runs like this: The American public is deeply ignorant about politics; this is problematic for a functioning democracy; this is unlikely to change in the future; the best and fairest way to address this is to decrease the number of functions that government performs and to encourage people to “vote with their feet.”

I’m going to focus my questions and/or critiques on the beginning of Ilya’s argument: Are American voters really ignorant, at least in ways that matter? I should acknowledge up front that a lot of what I’m about to write is addressed to varying degrees at other points in Ilya’s book, but for purposes of our discussion, it seemed best to start with the argument laid out in Ilya’s précis here.

How much knowledge does the voting public really need to have?

It appears the electorate would fare poorly in a political trivia contest. To take some examples from the 2000 American National Election Study, only about a third of voters knew the crime rate had decreased in the 1990s, only 19 percent could identify Dick Cheney’s home state (although there was some reasonable debate regarding whether it was Texas or Wyoming), only nine percent knew who Trent Lott was, and only four percent could name a second candidate for House of Representatives in their district.

As I pondered this, I realized that I couldn’t name the (admittedly obscure) candidate who ran against my own Representative in the previous cycle, despite the fact that I follow congressional elections for a living. If professional elections analysts are part of the problem, then we might be beyond any solution.

But then, why do we really care if voters don’t know where Dick Cheney is from, or who leads Great Britain? Over 70 percent of voters did know that Al Gore favored a higher level of spending than George W. Bush. In 2008, 76 percent of voters knew that Barack Obama supported a timetable for withdrawal from Iraq, while 62 percent knew that John McCain had opposed such a timetable. In 2010, 77 percent of voters knew that the deficit was larger than it had been in the 1990s, and 73 percent knew that Congress had passed a health care law.

These were the key issues for most voters in these elections. Since voters only have a binary choice, it might be perfectly rational to learn only about the most salient issues, while ignoring issues like abortion or the direction of the crime rate. As for those who truly know nothing, theoretically their votes should behave randomly, cancel each other out, and leave us with an election decided by informed voters.

How confident are we in judging voters’ knowledge of policy?

One of the implicit (at times, explicit) assumptions in the book is that there’s a clear “truth” on important policy questions that we might expect informed voters to arrive at, and that uninformed voters fall short of attaining. If this were clearly true, we might well be justified in limiting the polity’s ability to engage in certain forms of legislating.

Of course, there are differences of opinion, even among elites, on many if not most important policy questions. Beyond this, we should consider the possibility that the universe of “knowable” facts on any particular policy questions dwarfs our current knowledge base.

I call this the “Theodoric of York” problem, taken from an SNL sketch from the 1970s where Steve Martin plays a medieval barber. Asked to diagnose a villager’s daughter, he replies: “Why, just fifty years ago, they thought a disease like your daughter’s was caused by demonic possession or witchcraft. But nowadays we know that Isabelle is suffering from an imbalance of bodily humors, perhaps caused by a toad or a small dwarf living in her stomach.”

This is actually profound. I’m not sure there is a major academic discipline that hasn’t been revolutionized at least once in the past 100 years. You can’t read an old history textbook without chuckling, or groaning, at the depictions of Native Americans and our founding fathers’ virtues. Early climatologists wondered whether farming begat rainfall. Phrenology and theosophy were hot areas of “scientific” inquiry at one time or another.

More pertinently, Ilya cites the early 1930s as an instance of the public perhaps behaving rationally in its voting. But contemporaries wouldn’t have seen it that way: Raising tariffs was seen as the correct response to a recession, while following the “real bills doctrine” was seen as a no-brainer. Thirty years ago, there would have been something approaching a consensus among economists that the minimum wage hurts employment, but subsequent research has whittled away at this consensus.

Of course, we can’t forget that negative eugenics was once endorsed almost unanimously by our Supreme Court; Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous “three generations of imbeciles are enough” quote is a chilling reminder of this.

Had public opinion polling been available in the 1920s and revealed an electorate opposed to these policies, a contemporary academic would probably have shaken his head in despair. Yet today, we would judge the average American correct in most of these instances. We like to think we’ve learned since then, but have we really?

Compared to the average American, I suspect my understanding of economics is considerably greater. Yet compare me to Paul Krugman, and my knowledge base looks a lot like that of the average American. I suspect that if we were all compared to that elusive whole body of knowledge regarding how to fix health care policy or economics, our differences would resemble those among different varieties of atoms being compared to the sun.

We like to think that we know a lot about policy and that our compatriots’ knowledge base is depressingly small. But we should have some humility about this. In the big picture our differences aren’t that great, and probably they aren’t enough to justify limiting what the electorate can opt to do.

Doesn’t The Public Get It Mostly Right?

Let’s be instrumentalists for a second. Hasn’t the public done a reasonably good job of electing leaders over our country’s lifetime? There are certainly failures, but I think those failures are the exception and not the rule.

For example, can we clearly say that Bob Dole should have been elected over Bill Clinton? Did Jimmy Carter really deserve a second term, or Michael Dukakis a first? If you have strong ideological priors, you might say “absolutely,” but from a more detached perspective, I think most people would say we’ve done pretty well in our elections.

We once had a narrow electorate comprised largely of educated landholders. Yet our ability to choose wisely doesn’t seem to have declined as we’ve moved away from that. There’s no statistically significant relationship between the passage of time and the ratings of the presidents – and the early electors had the advantage of selecting from the Founding Generation! A recent electorate might have given us Richard Nixon, but the early electors very nearly gave us President Aaron Burr.

Nor does the electorate seem to be behaving irrationally today. Instead, it seems to be employing shortcuts reasonably well. Exit polling from 2012 reveals that overwhelming numbers of liberals voted for the more liberal candidate, while conservatives, especially white conservatives, voted for the conservative candidate; moderates split their vote. People who wanted the health care law repealed backed Romney, while those who wanted to keep it backed Obama. The list goes on, but whatever process voters are employing, they seem to be at the very least selecting candidates who line up with their worldviews.

In the end, a relatively low-information electorate has helped produce one of the most prosperous, most free societies in world history. This country has adopted many policies that economists seem to deem beneficial: tax rates have fallen, deductions have been reduced, and global trade has grown. We’ve become more tolerant with regard to racial, gender, ethnic, and sexual minorities. Sometimes this has come with a push from the courts (but see Gerald Rosenberg’s The Hollow Hope), but there’s no doubt that the will of the people has played a key role as well. I might hope for a more educated populace, but at the end of the day, I’m not sure American electorate is so broken that it demands the sort of fix that Ilya suggests.

Ignorance, Yes. Rational, No.

Ilya Somin’s Democracy and Political Ignorance is a welcome gust of realism in the corridors of political theory, where democracy is too often considered in the abstract, isolated from the actual traits and tendencies of democratic decision makers—that is, voters.

Ever since the 1930s, empirical research has consistently found that voters in America, and often in other countries, are far less knowledgeable about politics and policy than most people assume.1 Once we recognize the breadth and depth of public ignorance, as Somin helps us to do, we can no longer take it for granted that elections or opinion polls express deeply considered popular “mandates.” Even if they did, the basis of a mandate in sparse (or faulty) information calls its own validity into doubt. Therefore, Somin concludes, we should shift power from collective into individual hands, where people are likelier to make better decisions.

While I wish I could endorse Somin’s book and its conclusions without reservation, they rest on an illogical and empirically discredited foundation: the theory of rational ignorance. Anyone trying to base small-government conclusions on rational-ignorance premises is building a castle on sand.

Rational ignorance theory is partly grounded in the mathematical truth that in a large electorate, the odds are extremely low that a single vote will decide an election. But this fact alone cannot explain voters’ behavior unless we assume that it is a fact of which voters are aware. Only if they know that their votes are highly unlikely to matter is it possible that they’ll decide not to invest in becoming politically well informed, since they recognize that this would be a waste of their time.

There is a libertarian payoff to this theory, since at first glance it seems that voter ignorance cannot be alleviated: no matter how hard we try to get people to pay attention to politics, it would be irrational for them to do so. Because ignorance is baked into democratic government, we should reduce the power of democratic governments, other things equal.

However, the libertarian conclusion does not follow from the rational ignorance premise. Rational ignorance theory blames public ignorance on the low incentive to become a well-informed voter. Raise the incentives and you solve the problem. One way to raise the incentives would be to make government far more powerful than it now is, so that everyone had a much higher stake in electoral outcomes.Another solution would be to turn state power over to highly knowledgeable experts who would be fired or even fined if their policies didn’t work.

Fortunately, such solutions are not advisable, because the theory of rational ignorance is false. Somin provides no evidence that many voters are aware of the likely insignificance of their vote, and there is overwhelming evidence against it.

Part of the evidence is on page 74 of Somin’s book, where it emerges that 70 percent of American voters think that their individual votes “really matter.” Unfortunately, by page 74 Somin is explicating rational ignorance theory and doesn’t step back to notice the devastating implications of this datum for the theory’s key premise: that voters know that their votes aren’t likely to matter. Similarly, the Citizen Participation Study shows that 89 percent of voters say that influencing government policy is either a very important or a somewhat important reason for having voted, which would hardly make sense if they understood the utter insignificance of each vote in a sea of tens of millions of other votes.2 Finally, if you don’t trust opinion polls, there is the fact that 100 percent of voters vote. Why would they do this if they thought their votes inconsequential?3

The fact that voters vote despite the astronomical odds against their votes being decisive is what political scientists call the paradox of voting. As a leading scholar of public opinion (himself a rational choice theorist) once put it, this is “the paradox that ate rational choice theory”—including rational ignorance theory.4 Voters who know that their votes are unlikely to matter should not only fail to inform themselves politically; they should also fail to vote. The fact that voters vote, along with the polls showing that they think their votes do matter, indicates that the premise of rational ignorance theory is false.

That is hardly surprising. We grow up in a democratic culture suffused with voting, starting in kindergarten, and at every step of the way we’re bombarded by propaganda assuring us that every vote counts. People tend to believe what they’re told unless it’s challenged and challenged early. But most people have never heard the challenge posed by economists and political scientists, such as Somin, who have calculated the infinitesimal chance that a vote will “count.” I’ve never taught a political science course in which more than one or two students had even heard of the idea that one’s vote may not be decisive (something that is hardly “intuitive,” as Somin claims: it took economists until 1957 to figure it out).5 It’s not that most students have “overestimated” the odds that their vote will be decisive;6 it’s that they’ve never even asked themselves the question. The whole issue of the decisiveness of their vote is an unknown unknown for them.

Somin’s solution to the paradox of voting only deepens the problems for rational ignorance. He constructs formulae showing that if a voter (1) attributes a high enough benefit to his party’s or candidate’s election, (2) multiplies this benefit by a high enough estimate of his chance of affecting the outcome, and then (3) subtracts from this benefit the cost of voting as compared to the cost of becoming politically well informed, he will conclude that going to the polls is worthwhile but that becoming well informed (which Somin assumes will be more expensive than the cost of voting) is not. So voters’ calculations, conducted at an “intuitive” level,7 tell them to vote, but to vote ignorantly.

Let’s set aside the implausibility of this scenario given that there’s no evidence that it has even occurred to most voters that their votes may be inconsequential. There is also a problem of pure logic. If voters can plug into Somin’s formulae even a vague estimate of the benefit of their party’s or candidate’s victory, then they must think that they know enough about this benefit to be able base their vote on this knowledge. Somin and other political scientists may think that voters should know a lot more than they do, but voters seem to think, even in Somin’s account, that they know enough that they can roughly guess who to vote for. And that’s all they need to know if they are to falsify rational ignorance theory, for, according to the theory, they should be deliberately underinforming themselves. But if they did indeed deliberately underinform themselves (by their own standards), then, of necessity, they wouldn’t be able to calculate the benefits of voting, because they wouldn’t think that they could predict the benefits of a given candidate’s or party’s victory.

It seems to me that this logical truth is fatal to rational ignorance theory, which not only assumes that voters know that their votes probably won’t matter, but also assumes that, in consequence, voters deliberately fail to inform themselves adequately—not adequately according to Somin, or adequately when judged against a standard of perfect knowledge, but adequately enough to be able to vote for one candidate rather than another.

Many voters doubtless realize that they are less than “fully” informed. We all know we could spend more time reading newspapers, etc. But that would be true even if we devoted all of our time and energy to following politics: in politics, as in everything else, there is always more to learn. What matters for rational ignorance theory is whether voters deliberately choose not to inform themselves enough (by their own standards of adequacy). But if they are able to choose one candidate, party, or ballot proposition over the others, then they must think they have information adequate to this task.

My argument could be falsified if voters flipped a coin after closing the voting curtain. Then we could reasonably conclude that they knew they were too underinformed to make a rational choice between the candidates. Surely on obscure propositions and minor offices, many voters do flip a coin—or refuse to cast a vote. But rational ignorance theory cannot explain what Somin is trying to explain: hundreds of millions of nonrandom votes on important matters.

Somin anticipates this line of argument by attributing another intuition to his supposedly ignorant voters (whose gut feelings seem to more than compensate for their lack of knowledge): the intuition that “to be an adequately informed voter, it might help to know the names of the opposing candidates, the major policies adopted by the government in recent years, and which officials are responsible for which issues.”8 Somin is saying that since everyone recognizes that they need to know such things in order to cast an intelligent vote, voters (who don’t usually know these things) must have concluded that voting intelligently isn’t worthwhile. But once again, survey data suggest that Somin is mistaken. For example, in a Pew poll taken in July 2012 (a full four months before the election), 90% of the respondents said they already knew what they needed to know about Obama in order to decide how to vote, and 69% said they knew what they needed to know about Romney.9 Clearly Somin’s criteria for being adequately informed are higher than most voters’ criteria. This means that they aren’t deliberately underinforming themselves.

One can easily confirm this fact by talking to ordinary voters, who are well aware that they aren’t omniscient but who have political opinions anyway. The same goes for Somin’s wholesale adoption of the theory of “rational irrationality”10 to analogize highly informed ideologues to sports fans who, for the sheer fun of it, willfully ignore unfriendly arguments and evidence. If one actually talks to ideologues, one finds find that they firmly believe they’re in possession of the obvious truth. The reason they dismiss counterarguments and counterevidence is that they think such arguments and evidence are implausible: they contradict things that any sane person knows to be true.

In both ignorant voters and dogmatic ideologues we have a good starting point for a truly realistic theory of politics. If voters don’t think they need to know very much if they’re to cast adequately informed ballots, they must think that our society is a mighty simple place, where it doesn’t take much information to be able to identify good policies and good politicians. The same is true of ideologues, who treat their views as reflections of obvious truths about society. (I know Somin would agree with me that modern society is more complicated than that, since he brilliantly demolishes as simplistic many decisionmaking heuristics commonly used by voters.)

That society is too complex to yield easy political answers is the most important fact of which most voters seem to be ignorant. But if so, it is not because they have calculated that it would be a waste of time to learn that society is more complicated than they think it is. It is because the complexity of modern society is, to them, an unknown unknown.

Notes

1 For a survey of the early literature, see Jeffrey Friedman, Editor’s Introduction to Political Knowledge, 4 vols. (Routledge 2012). The best compendium of evidence is in Angus Campbell et al., The American Voter (1960). The most succinct and lively analysis of the findings is in Philip E. Converse, “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics” (1964), republished in Critical Review, vol. 18, nos. 1-3 (2006).

3 The Civic Participation Survey shows that 95 percent of voters rate “civic duty” as an important reason for voting (ibid.). But a duty to vote for harmful policies makes no sense. Nor does a duty to vote randomly. That leaves only a duty to cast a helpful vote, one that will serve the public interest (or one’s own interest). Anyone who felt a duty to vote must therefore feel an equal duty to make it an adequately informed vote, since only if it were adequately informed could it be expected to serve either the public’s interest or one’s own.

4 Morris P. Fiorina, “Information and Rationality in Elections,” in Information and Democratic Processes, ed. John Ferejohn and James Kuklinski (1990), p. 334.

9 Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Most Voters Say They Already Know Enough about the Candidates,” July 24, 2012.

The Conversation

Of Parties, Moving Costs, Hedgehogs, and Foxes: Reply to Heather Gerken

I would like to start by thanking Heather Gerken for her thoughtful response to my lead essay and book. Gerken raises two important potential criticisms of my argument that people make better decisions through foot voting than ballot box voting. First, she contends that knowledge of the two major parties’ positions can enable otherwise ignorant voters to make good decisions at the ballot box. Second, building on the important work of my colleague David Schleicher, she worries that foot voting may often be too difficult because of moving costs.

These are legitimate points, and I address both at some length in my book.[1] On balance, however, neither seriously undermines the informational advantages of foot voting over ballot box voting.

Parties

Party labels are often a useful information shortcut. By knowing that Candidate X is a Democrat or Republican, voters can also know a good deal about his or her positions on various issues, even if they know nothing else about that person. Unfortunately, this is not enough for voters to make an informed decision at the ballot box. Even if a voter has excellent information about the policies a given candidate will pursue in office, it is also important to have some idea of the likely effects of those policies. If a given party runs on a platform of helping American industry by increasing protectionism, or making the streets safer by ramping up the War on Drugs, is that actually likely to help the economy or reduce crime? Voters ignorant of basic aspects of politics and economics (as most often are) are poorly equipped to answer such questions. For example, polls show that the majority of the public believes that protectionism helps the economy, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary endorsed by economists across the political spectrum.

Even if the party information shortcut does help voters make good choices between the platforms offered by the Republicans and Democrats, those platforms themselves would likely be different and better if the public were less severely ignorant about policy. Parties choose their platforms at least in large part to maximize their chances of winning elections. Platforms that effectively appeal to a generally ignorant electorate are likely to be different from – and of lower quality – than those that might appeal to a much better-informed one. Scholars such as economist Bryan Caplan and political scientist Scott Althaus find that there are huge differences between the views of well informed and poorly informed voters, even after controlling for a wide range of other variables, such as race, gender, income, and ideology.[2]

In addition, voters often do a poor job of figuring out the positions of the parties themselves, often overlooking even major shifts in their stances. For example, over the last forty years, the public has barely altered at all in its perceptions of the ideologies of the two parties, despite such major developments as the rise of Reagan and the New Right, Bill Clinton’s centrist “New Democrat” platform, the ascendancy of Barack Obama in the Democratic Party, the growing influence of the Tea Party movement since 2009, and others.

In one important respect parties actually make the problem of political ignorance and irrationality worse rather than better. Many voters develop strong party loyalties that skew their perceptions of reality. For example, Republicans tend to overestimate the rate of inflation and unemployment when there is a Democrat in the White House, and they underestimate it when the president is a Republican. Democrats have the opposite bias.[3] Rather than judge parties by their records, partisans judge records by their feelings about the party in power. Obviously, swing voters usually don’t have such strong partisan biases. But swing voters are also the least knowledgeable about politics and public policy in general.[4]

Gerken interestingly contrasts my “fox”-like view that informed voting requires knowledge of a range of issues with the “hedgehog” view that all voters need to know is the difference between the two parties. It’s worth noting that Philip Tetlock’s important research on the predictive accuracy of policy experts shows that “fox” experts who take many variables into account make far more accurate judgments than “hedgehogs” who focus only on one or two big ideas.[5] Voters obviously don’t need to know as much as policy experts. But narrowly focused hedgehog decisionmaking is unlikely to work well even for them. It is especially problematic in a world where government addresses such an enormous range of complex issues. Hedgehog voters and hedgehog policy experts might do better if the functions of government were fewer and simpler.

Foot Voting and Moving Costs

Gerken is absolutely right to point out that foot voting often involves significant moving costs. This is indeed an important constraint. But it is far from prohibitive. In the modern United States, some 43% of Americans have moved between states at least once in their lives, and 63% have at least made moves within a state (usually switching local governments in the process).[6] Migrations towards states and localities with relatively more effective governments and away from dysfunctional ones are quite common. The poorly governed city of Detroit’s massive loss of population over the last several decades is a particularly dramatic example.

In addition, much can be done to reduce those costs further. [7] By decentralizing power to local as opposed to state governments, we can offer foot voters a wider range of options within a relatively short geographic distance. In this way, people can vote with their feet without having to give up job opportunities, social ties, or the benefits of “agglomeration” stressed in David Schleicher’s work.[8] Some unusually large jurisdictions, such as Los Angeles or New York City, could potentially be broken up into several smaller cities in order to facilitate foot voting by residents and prevent any one local government from gaining monopoly power. The same point also applies to unusually large states, such as Texas or California, though state boundaries are politically far more difficult to rearrange than local government boundaries. Heather Gerken herself has done excellent work on the benefits of pushing federalism “all the way down” to the local level.[9] My own work reinforces her case.

Moving costs can be reduced still further by leaving more issues to be decided through the private sector rather than the public. In the market and civil society, people can often switch service providers without having to move at all. Over 50 million Americans already live in private planned communities, which provide many services traditionally associated with local governments. Moving between private planned communities is not costless, but it is far easier than moving between cities or states.

We cannot decentralize or privatize all of the functions of government. Some problems are so large that they can only be effectively addressed at the national level – or even the global one. We also cannot completely eliminate moving costs. But many of the world’s best-governed nations – such as Denmark, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Singapore, are much smaller than many US states, and, in the latter two cases, even many American cities. This suggests that we can do a great deal of decentralization without losing much in the way of beneficial economies of scale.

My book does not offer a complete theory of federalism, or of the role of government more generally. But the informational advantages of foot voting are a good justification for shrinking and decentralizing the state more than we might otherwise.

Notes

[1] See Ilya Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 93-97, 144-45.

[2] See Bryan Caplan, The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Scott Althaus, Collective Preferences in Democratic Politics, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[3] For a discussion of these types of partisan biases, see Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 95-97.

[4]Ibid, 111-12.

[5] Philip Tetlock, Expert Political Judgment: How Good is it? How Can We Know? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

[6] Pew Research Center, Who Moves? Who Stays Put? Where’s Home? (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2008), 8, 13.

[7] For a fuller discussion, see Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 137-39, 144-45.

[8] David Schleicher, “The City as a Law and Economic Subject,” University of Illinois Law Review (2010): 1507-64.

[9] Heather Gerken, “Foreword: Federalism All the Way Down,” Harvard Law Review 124 (2010): 4-74.

Do Voters Know Enough to Make Good Decisions on Important Issues? Reply to Sean Trende

I would like to thank Sean Trende for his kind words and thoughtful analysis. Sean offers three important criticisms of the argument advanced in Democracy and Political Ignorance: that voters know enough to make good decisions on really important issues, that they can make good choices between the two options on offer in major elections, and that the historical success of American democracy suggests that political ignorance may not be such a serious problem. Each of these points has some merit. But each is overstated. Political ignorance does not prevent voters from making good decisions in some important situations. But it does make the performance of democracy a lot worse than it would be otherwise.

Voter Knowledge on the Big Issues

Sean emphasizes that even if voters are often ignorant, they usually at least understand the big issues in an election. This is sometimes true, but far less often than he supposes. For example, Sean cites the 2010 midterm election as one where the voters were well-informed about big issues. According to the majority of Americans at the time, the most important issue was the state of the economy. Yet preelection polls showed that 67% of voters did not even realize that the economy had grown rather than shrunk during the previous year. The majority also did not know the basics of the 2009 stimulus bill, the most important policy adopted by the Obama administration to try to promote economic recovery. Moreover, a plurality believed that the 2008 bailout of major banks enacted to try to contain the financial crisis and recession that occurred that year – had been enacted under Obama rather than under President George W. Bush (only 34% knew the correct answer).1

As Sean notes, over 70% of the public in 2010 did know that Congress had recently passed a health care reform law. But polls throughout 2009 and 2010 repeatedly showed that most of the public had little understanding of what was actually included in that law. As I noted in my lead essay, extensive public ignorance about Obamacare persists to this day, even though it has been a high-profile political issue for years. Knowing that Congress has passed a health care reform law is only of very limited utility if you don’t know what the law does. This kind of ignorance about major issues was far from unique to 2010. There was comparable ignorance in numerous other elections, some of which I discuss in detail in the book.

In addition, ignorance sometimes dictates what voters consider to be important issues in the first place. For example, as I noted in the lead essay, most of the public greatly underestimates the percentage of federal spending that goes to entitlement programs, while overestimating that which goes to foreign aid. A public better-informed on these issues would likely put a higher priority on entitlement reform.

Voters don’t always get every issue wrong. To the contrary, they do get some important things right, especially if the issue is relatively simple and if the incumbents have committed some major error whose effects are obvious even to relatively ignorant voters. One such case, noted by Sean, was the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, when the voters justifiably punished Herbert Hoover and the Republican Party for their poor performance. But even in that instance, voter ignorance then led the public to support a number of severely misguided policies over the next few years, including the cartelization of much of the economy in ways that raised prices for the poor and increased unemployment relative to what they would have been otherwise. And in most cases, the relative success or failure of the incumbent party is much less glaring than it was in 1932.

Sean is right that some issues are complicated enough that even highly knowledgeable voters are likely to make mistakes. But knowing basic facts about the issues is likely to at least reduce the error rate substantially, even if it cannot eliminate all errors. Moreover, on many issues the public persists in serious errors that the vast majority of knowledgeable experts on both sides of the political spectrum condemn. For example, economists overwhelmingly agree that free trade is good for the economy, yet the majority of the public consistently believes otherwise. Similarly, both liberal and conservative economists oppose our massive system of farm subsidies, which mostly reward large agribusinesses. Yet these subsidies persist and grow, in part because much of the public is unaware of what they do, and in part because majority opinion believes that we might experience food shortages without them.

The Binary Choice Fallacy

Sean also argues that voters only need sufficient knowledge to make good choices between the options put before them by the major parties. In the book, I call this commonly advanced argument the “binary choice fallacy,” because it relies on the false assumption that all voters do is choose between two preset alternatives. As I spelled out more fully in my response to Heather Gerken, the argument is a fallacy because the candidates and platforms put forward by the major parties are themselves heavily influenced by voter ignorance. If the public were more knowledgeable, the parties would have strong incentives to put forward better candidates and policies.

Even in their choices between the candidates and parties actually on offer in particular elections, I am less confident than Sean that the electorate usually makes the right decision. I don’t have the time and space get into the relative merits of specific elections and candidates. But, at the very least, the wisdom of many of the public’s binary decisions in recent elections is far from clear.

Like some other scholars, Sean suggests that, even if many voters are ignorant, the mistakes of the ignorant will cancel each other out, thereby allowing more knowledgeable voters to determine electoral outcomes. This is a theoretically possible result. But, it rarely happens in practice. In reality, the effects of ignorance are usually not random, but systematic. On a host of issues – including major economic and social policy questions – the views of relatively more informed voters are hugely different from those of relatively ignorant ones, even after controlling for other relevant variables, such as age, race, sex, and partisan identification.2

Political Ignorance in American History

Sean’s most far-reaching claim is that the relative historic success of the United States suggests that voter ignorance is not such a big problem. This raises so many major issues that I can’t even begin to do justice to them in a brief post. But here are a few relevant points.

In calling the United States successful, we have to ask, “relative to what?” The answer, of course, is relative to other nations, nearly all of which are either democracies that also suffer form problems caused by political ignorance, or dictatorships. I do not deny that dictatorships are, on average, much worse than democracies.3 But the relative superiority of the United States compared to dictatorships and most other democracies is not relevant to the issue I raise in the book: whether democracies would suffer less damage from political ignorance if they limited and decentralized their governments more than they do at present.

During most of its history, the U.S. government was both more limited and more decentralized than most other democracies. The large size, limited central government, and numerous diverse jurisdictions of the United States gave Americans numerous opportunities to vote with their feet. And the informational superiority of foot voting over ballot box voting is, of course, a central thesis of my book. Extensive opportunities for foot voting, rather than ballot box voting, historically made the United States unusual.

Despite America’s relative success, there are numerous historical cases where American voters committed terrible mistakes in large part because of political ignorance. For many decades, the majority of white Americans supported first slavery and later segregation in part because they were badly misguided in their views of the likely consequences of giving blacks equal rights. More recently, public ignorance about the nature of homosexuality was a major factor in promoting widespread discrimination against gays and lesbians. Ignorance of basic economics contributed to public support for numerous protectionist laws, including the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which significantly exacerbated the Great Depression. These and other well-known examples merely scratch the surface. Scholars have only begun to document the historical impact of voter ignorance on public policy.

Sean could point out, correctly, that many of these ignorance-induced policies enjoyed substantial support among knowledgeable elites as well. However, in nearly all of the cases where we have relevant survey data, more knowledgeable people were significantly less likely to support harmful policies. Survey data going back to the 1930s and 40s shows that more knowledgeable whites were more likely to be racially tolerant. In recent decades, more knowledgeable heterosexuals have been more tolerant of gays and lesbians. Knowledgeable voters are also more likely to oppose protectionism, and they have been for decades. If we had better data on 19th century public opinion, I strongly suspect that more knowledgeable voters would have been more likely to, for example, support abolitionism and equal rights for women. In these and many other cases, a more knowledgeable electorate would likely have made fewer egregious errors and corrected those it did make faster.

In sum, it is certainly true that an ignorant electorate can still sometimes make good decisions. But all too often, widespread voter ignorance is not good enough for government work.

Notes

1 For data on these three instances of political ignorance in 2010, see Ilya Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 22

2 I criticize this and other “miracle of aggregation” arguments in much greater detail in the book. See ibid., pp. 109-17.

3 Ibid., 8-9, 103-04.

Why (Most) Political Ignorance is Rational and Why it Matters: Reply to Jeffrey Friedman

In his critique of my book, Jeffrey Friedman continues his longstanding efforts to show that most political ignorance is inadvertent rather than rational. In his view, voters are ignorant because they believe our society “is a mighty simple place” and “think they have information adequate to [the] task.” They simply don’t realize there is lots of other information out there that could help them make better decisions.

Friedman is a top-notch political theorist who has made valuable contributions to the literature on political knowledge.1 But on this point, I think he is barking up the wrong tree.2 Moreover, the mistake is of more than theoretical importance. Inadvertent ignorance has very different implications for political theory than rational ignorance.

Inadvertent Error Cannot Explain the Sheer Depth and Persistence of Political Ignorance.

Inadvertent error might explain why voters ignore highly abstruse (though potentially relevant) bodies of knowledge. But it cannot account for widespread ignorance of very basic facts about politics and public policy. For example, as I noted in my response to Sean Trende, two-thirds of the public in 2010 did not know that the economy had grown rather than shrunk during the previous year, even though most said that the economy was the single most important issue in the election. Similarly, most had little if any understanding of the Obama health care plan, another major issue. If you think the economy or the president’s health care plan is the biggest issue on the public agenda, it isn’t rocket science to figure out that these basic facts are highly relevant. Yet the majority of the public is often ignorant of such basics.3

The inadvertence theory also cannot explain why political knowledge levels have remained largely stagnant for decades, despite massive increases in education and in the availability of information through the media and modern technology, such as the Internet. These developments have made it much harder for voters to remain unaware of the reality that there are vast bodies of knowledge out there that are likely to be helpful in making political decisions. Americans have been quick to take advantage of these technological developments in their capacity as private sector consumers. But not, for the most part, in their role as voters. This is a striking divergence that the inadvertence theory cannot account for, but rational ignorance easily can.

Friedman argues that his theory is supported by polls showing that most voters thought they had sufficient information to make a decision in recent elections. But this ignores the reality that the amount of knowledge we consider enough to make a relatively unimportant decision is often much smaller than what we consider enough to make an important one. I think I have enough information to conclude that The Hunger Games was probably the best movie of 2012, even though I haven’t even watched most of its competitors. But that’s in large part because I know that the correctness of my opinion on this issue isn’t very important. If I were solely responsible for deciding who should win the Oscar for Best Picture, I would study the issue much more carefully.

Friedman’s theory implies that the average voter would not bother to acquire significantly more information about politics if he suddenly learned that he would be part of a small committee tasked with picking the next president of the United States. I think the vast majority of people would take the decision a lot more seriously if that were the case, and would spend a lot more time learning and evaluating political information. Jurors who make decisions in small groups where each vote matters greatly perform better than voters in part for this very reason.4

In making decisions that are likely to have only a small effect, people naturally set lower standards of informational adequacy than in making decisions that are likely to make a big difference. Given limited time and cognitive ability, we have to make such tradeoffs all the time. Friedman assumes that people who choose to limit their acquisition of information would also take care not to form opinions on issues where there knowledge is very limited. But in fact, it is perfectly rational to form opinions on the basis of small amounts of information in cases where the cost of error is low.

This key distinction also explains why many people choose to vote, but do not choose to learn very much about the issues they are voting on. Voting usually requires very little time and effort, while studying more than minimal amounts of political information requires a lot. People with a modest sense of “civic duty” are willing to spend modest amounts of time and effort on activities that have only a small chance of making a difference. But, given the odds, they are unlikely to make big sacrifices or to set high informational standards.

Friedman suggests that most people can’t possibly be rationally ignorant about politics because the theory of rational ignorance was only developed by economist Anthony Downs in 1957, and to this day it is known by few nonexperts. But, like many economic theories, rational ignorance is simply a formalization of an intuition that people routinely apply in their everyday lives. People exploited comparative advantage in trade long before economists formalized that theory. Similarly, long before 1957, people learned to prioritize some types of information acquisition over others based on the likelihood that learning it would make a difference. The value of these formal theories lies not in giving counterintuitive advice to individual voters or consumers, but in their nonobvious implications for the large-scale operations of economic and political systems.

The Rationality of “Political Fans”

The same weaknesses that undermine Friedman’s critique of rational ignorance theory also undercut his critique of “rational irrationality” – the idea that people might rationally do a poor job of evaluating the political information they learn. Just as sports fans evaluate information in a way that is highly biased in favor of their favorite teams, “political fans” do so in a way that is biased in favor of their preferred party, candidate, or ideology.

Friedman protests that, unlike “sports fans who, for the sheer fun of it, willfully ignore unfriendly arguments and evidence,” ideologues “firmly believe they’re in possession of the obvious truth. The reason they dismiss counterarguments and counterevidence is that they think such arguments and evidence are implausible: they contradict things that any sane person knows to be true.” But if you talk to a dedicated sports fan, you will often find that he believes it’s “the obvious truth” that a disputable referee’s call that went against his team must be wrong, or that his favorite player is the best in the league, regardless of evidence to the contrary. Both sports fans and political fans tend to be dogmatic and closed-minded in large part because seeking truth is not the main reason why they chose to pursue these activities in the first place. Instead, they have motives such as entertainment, confirming their preexisting views, enjoying the camraderie of fellow fans, and so on.

That does not mean that either type of fan deliberately endorses conclusions they know to be false. With rare exceptions, fans sincerely believe that their opinions are true, often even “obviously” so. But in reaching this conclusion, they make little effort to objectively evaluate the relevant data, seek out opposing points of view, or otherwise behave as genuine truth-seekers do. Like information acquisition, objective evaluation of information requires time and effort. In addition, it can result in great psychological pain if it leads a fan to question cherished preexisting beliefs or reach conclusions that diverge from those of friends, family, and fellow fans. Even just reading opposing viewpoints can be unpleasant. Conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia recently said that he stopped reading the liberal Washington Post because it made him “upset every morning.” Numerous liberal political fans tend to avoid conservative publications for similar reasons.

Most people understandably prefer to avoid all that effort and pain unless there is some substantial offsetting benefit. Many of us have thoughts that we would rather not think, and information that we avoid because we would prefer not to know. When the truth might hurt, we are less likely to seek it out, and more likely to seize on any excuse for denying it.

Why it Matters

Widespread political ignorance is a menace regardless of whether it is rational or inadvertent. But the difference between the two explanations for it matters. Inadvertent ignorance is a much easier problem to address than rational ignorance.

We could probably make a major dent in the former simply by pointing out to people that they are overlooking potentially valuable information. Just as warnings about the dangers of smoking convinced many people to quit, and warnings about the dangers of AIDS and other STDs increased the use of contraceptives, so warnings about the dangers of political ignorance and suitably targeted messages about the complexity of political issues could persuade inadvertently ignorant voters to seek out more information. It could also lead them to be more objective in evaluating that information.

With rational ignorance and rational irrationality, by contrast, such simple solutions are far less likely to work. Rationally ignorant people choose not to acquire new knowledge because the incentive to do so is weak, not because they are blissfully unaware of the possibility that additional knowledge could improve the quality of their voting decisions.

As Friedman points out, decentralizing and limiting government is not the only possible solution to rational ignorance. I devote an entire chapter of my book to considering other approaches, and explaining why they are less promising.5 Still, in weighing competing options, it helps to know what kind of problem we are trying to solve.

I don’t doubt, of course, that some political ignorance is inadvertent. Even the most careful truth-seekers sometimes overlook important information by mistake. But the magnitude and persistence of political ignorance and bias is more readily explained by rational behavior.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Jeffrey Friedman and Wladimir Kraus, Engineering the Financial Crisis, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

2 I give a more detailed critique of Friedman’s theory in Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 71-77.

3 I give many other examples in Ibid., ch. 1.

4 See Ilya Somin, “Jury Ignorance and Political Ignorance,” William and Mary Law Review (forthcoming), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2312806.

5 Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, ch. 7.