About this Issue

With much justification, the United States prides itself on guaranteeing a wide scope of religious liberty to people of all faiths and of none. Yet new issues in this area will constantly arise even in a generally successful and free legal order. Religious liberty may or may not be under assault on margins of varying importance, and a people intent on keeping or extending its religious liberty will need to be vigilant and to think carefully about the choices that are made in its court system.

This month we have invited four experts on U.S. religious liberty law to discuss recent and upcoming Supreme Court cases. They will offer a variety of perspectives, introducing themes and ideas from this area of law to interested readers in clear, accessible language, offering the best picture they can of the state of the debate among legal scholars. The Cato Institute’s own Ilya Shapiro has written the lead essay for the month; answering him will be David H. Gans, K. Hollyn Hollman, and Robin Fretwell Wilson. After each has responded, we will host a month of discussion on the issues they have raised. We look forward to readers’ comments during the month that the issue is live.

Lead Essay

Religious Liberty and the Fate of Civil Society

The state of religious liberty in America is muddled. On one hand, even as the population as a whole becomes more secular, we have a plethora of religious institutions and networks that run the theological gamut from Anglicans to Zoroastrians. Innovation and entrepreneurship is alive and well in a diverse religious sphere that would’ve been unrecognizable when the vast majority of Americans were regular churchgoers.

On the other, religious liberty beyond the bare freedom to worship is under threat from government mandates, weaponized antidiscrimination laws, and other intolerances brought on by the progressive left. For example, U.S. college campuses have become a hotbed of anti-Semitism even as such incidents decline worldwide (presumably because Jews are disfavored in the latest intersectional hierarchy of privilege). The rise of the alt-right doesn’t help.

The Supreme Court, for its part, has taken a middle stance—largely because these cases often turn on the whims of Justice Anthony Kennedy—making the government relent in cases like Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) and Zubik v. Burwell (2016) but not allowing student groups to restrict membership to actual believers in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez (2011). The Court hasn’t yet taken one of the wedding-vendor cases that ask whether religious businesses can be punished for declining to service same-sex weddings—but it can’t resist them forever.

And then you have a new presidential administration headed by an unlikely hero of the God-fearing. Indeed, Donald Trump owes his surprise election to a vast swath of religious voters—many of whom held their noses to pull the lever for a twice-divorced New York playboy. They likely thought (not inaccurately) that a Hillary Clinton presidency would’ve been more threatening to their interests, not least regarding Supreme Court and other judicial appointments. At the same time, this president rolled out his immigration-related policies in such a haphazard and under-lawyered way that they fed into the narrative that his executive actions have been anti-Muslim. And perceptions have not been helped by the statements candidate Trump made on the campaign trail.

It’s hard to synthesize the state of religious liberty in America given these countervailing trends, but let’s survey a few of the issues I’ve referenced.

Religious Exemptions from Federal Mandates

First, we have the issue of religious exemptions to generally applicable laws. Through most of American history, religious objectors only got relief if the law explicitly provided it. For example, Quakers were historically exempt from being drafted into the military. In the 1960s, however, the Supreme Court began recognizing constitutionally required exemptions. That experiment only lasted until 1990, when, in a controversial opinion (Employment Division v. Smith) by Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court ruled that generally applicable laws were valid so long as they don’t specifically discriminate against religious people. If religious objectors wanted an exemption from such laws, they would have to seek it from the legislature.

As it turned out, criticism of the decision came from all ideological sides; no part of the political spectrum was too pleased with the new rule on religious non-accommodation. Accordingly, Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), which created a presumptive statutory exemption from generally applicable laws, subject to the government’s showing that the burden it imposed on religious believers was “the least restrictive means of furthering [a] compelling governmental interest.” It may be strange to imagine two decades hence, but under the leadership of then-Rep. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), RFRA passed unanimously in the House and by a 97-3 vote in the Senate before being signed by President Bill Clinton.

That’s where things stood when the Affordable Care Act came along. Given Obamacare’s myriad constitutional and civil-rights violations it should be no surprise that it caused the latest legal battle involving government intrusion on religious liberty.

Take the contraceptive mandate cases, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014, regarding for-profit companies) and Zubik v. Burwell (2016, regarding nonprofits). The government claimed that these were about ensuring that all women had access to contraception. Many in the media (and several senators), purporting to be concerned about women’s rights, claimed that the issue was whether employees would have access to birth control despite their employers’ religious objections. Those on the other side argued that the case concerned every American’s right to freely exercise religion.

David and Barbara Green, who own the Hobby Lobby chain of arts-and-crafts stores, had long provided healthcare benefits to their employees (they believe it is their Christian duty), but they had not paid for abortions. A regulation interpreting the ACA’s instruction to cover “preventive care” required them to pay for their employees’ contraceptives—including those that can prevent the implantation of fertilized eggs, which the Greens consider to be an abortifacient and therefore against their religious beliefs. The alternative was to pay $1.3 million in daily fines. Nonprofits like the Little Sisters of the Poor had broader objections, but nobody disputed that they were religious organizations to begin with.

These cases, however, were not ultimately about balancing religious liberty against other rights. Hobby Lobby involved a simple question of statutory interpretation regarding whether the government was justified there in overriding certain religious objections. Zubik asked whether the government was doing all it could to accommodate religious groups, as RFRA required. The Supreme Court evaluated these questions and ruled that (1) closely held corporations can’t be forced to pay for every kind of contraceptive for their employees if doing so would violate their religious beliefs, and (2) that a better accommodation could be forged.

In both cases, the government failed its RFRA obligation to show that it had no less burdensome means of accomplishing its stated goal of providing female workers with “no-cost access to contraception.” There was no weighing of religion versus access to birth control. Nobody was denied contraceptives, and there’s now more freedom for all Americans to live as they wish, without being forced to check their consciences at the office door.

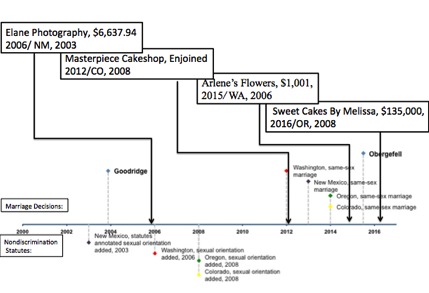

State Public Accommodations Laws

But what about state laws, which the federal RFRA doesn’t touch? That’s where another set of cases, which the Supreme Court has not yet considered, come in. Here we see infringement of religious liberty in the spillover from the gay marriage debates, with people being fined for not working same-sex weddings: the Washington florist, the Oregon baker, the New Mexico photographer, and many others. There’s a clear difference between arguing that the government has to treat everyone equally—the legal dispute regarding state issuers of marriage licenses—and forcing private individuals and businesses to endorse and support practices with which they disagree.

It’s disappointing but not surprising that Elane Photography lost its case, despite New Mexico’s own state RFRA. Despite gay-rights activists’ comparing their struggle to the Civil Rights movement, New Mexico is not the Jim Crow South, where state-enforced segregation left black travelers nowhere to eat or stay. A YellowPages.com search yields over 100 photographers in the Albuquerque area, most of whom would be happy to take anyone’s money.

Many of these cases implicate freedom of speech even before religious considerations. Take, for instance, a freelance writer who refuses to write a press release for a religious group with which he disagrees. Under several state courts’ theories, such a refusal would be illegal because it discriminates based on religion—much as Elaine Huguenin’s refusal to photograph an event with which she disagreed was treated as violating the law. Yet a writer must have the First Amendment right to choose which speech he creates, notwithstanding state law to the contrary.

Likewise with photographers and florists, who create visual rather than verbal expression. The Court has said repeatedly that the First Amendment protects an “individual freedom of mind,” which the government violates whenever it tells a person that she must or must not speak.

Upholding individual freedom and choice here would inflict little harm on those who are discriminated against. A photographer who views same-sex weddings as immoral would be of little use to the people getting married; there’s too much risk that the photographs will, even inadvertently, reflect that disapproval. Those engaging in such a ceremony—or, say, entering into an interfaith marriage, or remarrying after a divorce—would benefit from knowing that a prospective vendor looks down on their union, so they could hire someone more enthusiastic.

In starker terms, would you want Unitarians to work the audio equipment at a Southern Baptist revival? Would you force a Jewish printer to produce anti-Semitic flyers? Would you require Muslim butchers to serve pork ribs? For that matter, gay photographers shouldn’t be forced to work fundamentalist celebrations, blacks shouldn’t be forced to work KKK rallies, and environmentalists shouldn’t be forced to work job fairs in logging communities.

When someone tells you that she won’t work your wedding, you may understandably be offended. But avoiding offense isn’t a valid reason for compelling speech or behavior.

Religious Groups and Public Benefits

The final set of cases to arise lately involve the eligibility of religious organizations for generally available public benefits. Just last month, the Supreme Court heard argument in Trinity Lutheran Church v. Pauley, in which a Missouri church was denied a state playground-resurfacing subsidy on the sole ground that it was a religious institution.

Justice Anthony Kennedy opened the questioning by expressing concern for the use of religious status to deny government benefits. It was mostly downhill from there for the state, as Justice Samuel Alito launched into a series of hypotheticals regarding Homeland Security funds for terrorism prevention, grants to rebuild religious structures damaged in the Oklahoma City bombing, and other transfers to pay for certain non-devotional expenses. Justice Stephen Breyer also got into that mix, questioning how police, fire, and other public health protections were okay but making playgrounds safe was not. Even Justice Elena Kagan, at first skeptical of the church’s position, acknowledged discomfort with the burden Missouri had placed on a constitutional right.

Trinity Lutheran looks to be a 7-2 win for the church, but my basic position remains that while Missouri isn’t required to have a scrap-tire grant program, once it created one, it must open it to all without regard to religious status. The same logic applies to school-choice programs, whether based on vouchers or tax credits: the state Blaine Amendments that have been used to stymie these were created nationwide in the late 19th century not simply to separate church and state, but to harm minority religious sects, especially Catholics. Moreover, a state constitutional provision can’t trump the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits discrimination against religion.

Future Battles

Many of our culture wars are a direct result of government’s forcing one-size-fits-all public-policy solutions on a diverse nation. All these issues will continue to arise as long as those in power demand that people adopt politically correct beliefs or cease to engage in the public sphere.

The left’s outcry over religious free-exercise cases shows a more insidious process whereby the government foments social conflict as it expands its control into areas of life that we used to consider public yet not governmental. This conflict is exceptionally fierce because, as Megan McArdle put it, “the long compromise worked out between state and religious groups—do what you want within very broad limits, but don’t expect the state to promote it—is breaking down in the face of a shift in the way we view rights and the role of government in public life.”

Indeed, it is government’s relationship to public life that is changing—in places that are beyond the intimacies of the home but still far removed from the state, like churches, charities, social clubs, small businesses, and even “public” corporations that are nevertheless part of the private sector. Through an ever-growing list of mandates, rules, and “rights,” the government is regulating away our Tocquevillian “little platoons.” That civil society, so important to America’s character, is being smothered by the ever-growing administrative state that, in the name of “equality,” negates rights to standardize American life from cradle to grave.

The most basic principle of a free society is that government can’t force people to do things that violate their consciences. Americans understand this point intuitively. Some may argue that in the contraceptive-mandate cases there was a conflict between religious freedom and reproductive freedom, so the government had to step in as referee—and women’s health is more important than religious preferences. But that’s a false choice, as President Obama liked to say. Without the HHS rule, women are still free to obtain contraceptives, abortions, and anything else that isn’t illegal. They just can’t force their employer to pay the bill.

The problem that Hobby Lobby and Zubik exposed isn’t that the rights of employers are privileged over those of employees. It’s that no branch of our federal government recognizes everyone’s right to live his life as he wishes in all spheres. Instead, we are all compelled to conform to the morality that those in charge of the government have decided is right.

We largely agree—at least within reasonable margins—that certain things are general needs and their provision falls under the purview of the federal government, such as national defense, basic infrastructure, clean air and water, and a few other such “public goods.” But most social programs, many economic regulations, and so much else that government now does are subjects of bitter disagreements precisely because these things implicate individual freedoms—and we feel acutely, as Americans, when our liberties have been attacked.

The trouble is that when government grants us freedoms instead of protecting them, the question of exactly what those freedoms are becomes much less clear, and every liberty we thought we had is up for discussion—and regulation. Those who supported the religious believers in the contraceptive-mandate cases were rightly concerned that people are being forced to do what their deepest values prohibit.

What delicious irony it will be if Donald Trump saves us from this collectivized territory.

Response Essays

Religious Liberty in the Age of Trump

Ilya Shapiro argues that religious liberty is at risk, and that progressives are to blame. He writes that “religious liberty beyond the bare freedom to worship is under threat from government mandates, weaponized antidiscrimination laws, and other intolerances brought on by the progressive left,” and he argues that courts should play a muscular role in exempting religious objectors from these forms of government regulation. But the facts simply don’t fit Shapiro’s account. He all but ignores threats to religious liberty and equality that don’t fit into his narrative, including most notably President Donald Trump’s crusade against Muslims. In fact, Shapiro does not even discuss the Establishment Clause, which is just as much a part of the First Amendment as the Free Exercise Clause. In Shapiro’s analysis, free exercise looms large, while anti-establishment principles are wholly ignored.

Yet perhaps the biggest religious liberty cases of the day are the challenges to President Donald Trump’s revised travel ban in which courts around the country have barred Trump’s effort to make good on his campaign promises to enact a “Muslim ban.” The key issue in these cases is whether Trump’s travel ban violates what the Supreme Court has called the “clearest command of the Establishment Clause”: “one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.” This month, the Fourth and Ninth Circuits will hear the Trump Administration’s appeals from decisions by district courts in International Refugee Assistance Project v. Trump and Hawaii v. Trump, both of which held that the plaintiffs were to likely to succeed on their claim that the Muslim travel ban violates the Establishment Clause. By next term, one or both of these cases could reach the Supreme Court.

Trump’s effort to write religious discrimination into our immigration laws is a frontal assault on our constitutional first principles, and I would challenge Shapiro to admit as much. We face something much more serious than just some problems in the way the Trump Administration rolled out its policy.

Our Constitution’s Framers understood that immigration rules could be used to entrench a religious majority and disfavor a religious minority. In colonial Virginia, laws that required immigrants to swear an oath of the Anglican Church’s supremacy effectively kept Catholics out of the state. James Madison railed against such religious favoritism, observing in his famed Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments that “the first step … in the career of intolerance” is to place “a Beacon on our Coast,” warning the “persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion” that they must “seek some other Haven.” The Religion Clauses of the First Amendment, together with Article VI’s ban on religious tests for officeholding, ensure, in the words of George Washington, that “the Government of the United States … gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” The challenges to Trump’s Muslim travel ban present a huge test of fidelity to these founding principles. If Shapiro wants courts to vindicate religious liberty, these cases provide a sterling example.

Instead, Shapiro focuses primarily on a host of cases concerning the scope of religious exemptions from neutral laws, demonstrating that, in his view, religious liberty is primarily about exempting religious believers from laws that are applicable to all of us. These claims for religious exemptions, he argues, are a direct outgrowth of the fact that “civil society … is being smothered by the ever-growing administrative state that, in the name of ‘equality,’ negates rights to standardize American life from cradle to grave.” In discussing this topic, much of his essay covers familiar ground. He argues that the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Hobby Lobby was right. He thinks that Zubik, the sequel to Hobby Lobby in which the Supreme Court punted, should have come out the same way. Finally, Shapiro weighs in on Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, a case the U.S. Supreme Court is currently deciding whether to take. According to Shapiro, a business owner—such as a baker or photographer—who refuses to provide services to a same-sex couple for their wedding has a First Amendment right to discriminate that trumps any applicable anti-discrimination law.

Religious accommodations and exemptions are sometimes necessary to vindicate religious liberty. Thomas Jefferson famously argued that “it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” Sometimes, granting religious accommodation doesn’t harm others at all. The 2015 Supreme Court case of Holt v. Hobbs, in which the Justices unanimously granted a Muslim prisoner an exemption from an overbroad no-beard grooming policy, is a case in point.

But Shapiro champions the most suspect kind of religious exemptions: those that allow one party to impose their religious beliefs on another and extinguish their legal rights. Most troublingly, he offers no limiting principles of any kind. Shapiro’s argument would apply equally to a storeowner who claims that his religion commands racial discrimination, or to an employer who thought that providing family leave to a same-sex married couple made him complicit with sin.

Shapiro would empower business owners to impose their own religious beliefs on their employees and customers, who of course have religious convictions of their own. He would also extinguish important legal rights, such as, in Hobby Lobby and Zubik, rights to contraception coverage protected by the Affordable Care Act’s regulations or, in the wedding-vendor cases, anti-discrimination guarantees that require businesses to treat customers the same, without regard to race, sex, or sexual orientation. Making it easier for businesses to discriminate against employees and customers who don’t adhere to their religious code turns religious liberty on its head. Employees should not have their rights determined by their bosses’ religious views.

The Framing generation understood, in the words of one Pennsylvania minister, that “all … should have free use of their religion, but so as not on that score to burden or oppress others.” That’s why Framing-era conscientious objection laws often required Quakers and others opposed to combat on religious grounds to pay for or provide a substitute. But Shapiro views even the religious accommodation at issue in Zubik—which allowed religious objectors to opt out while third parties fulfill their legal obligations—as an affront to religious liberty. This is wrong. When the government acts to accommodate religion by allowing religious objectors to opt out and third parties to perform their legal obligations—as it has done for more than two hundred years in the context of military service—it respects religious liberty.

Shapiro claims that granting religious exemptions in the contraceptive coverage and wedding-vendor cases will not cause harm to anyone. He asserts that “women are still free to obtain contraceptives” and that “[u]pholding individual freedom and choice” by wedding-vendors “would inflict little harm on those who are discriminated against.” But Shapiro’s view of harm turns out to be unbelievably cramped and unmoored from the real world. IUDs—the most effective and also the most expensive form of birth control—are one of the kinds of contraceptives Hobby Lobby and others refused to cover; without insurance coverage, many women won’t be able to obtain them. Shapiro makes much of the fact that same-sex couples have a wide choice of potential florists or bakers, but discrimination is harmful whether or not you can go elsewhere to get the services you want. Indeed, that is why the law prohibits the sting of prejudice from discrimination. Under strict scrutiny, prohibiting discrimination—whether on account of race, sex, or sexual orientation—furthers a compelling governmental interest that cannot be advanced through less restrictive means.

Shapiro is a libertarian opposed to wide swaths of government regulation. But repackaging libertarian arguments against government regulation into claims of religious liberty does not make them more persuasive. It simply produces a perverted understanding of religious liberty that elevates the rights of corporations and business owners over those of workers and consumers.

Partisanship and Exaggeration Threaten Religious Liberty in America

Ilya Shapiro’s essay on religious liberty is written in a way that mirrors many of our current public policy debates. He mentions disparate phenomena and identifies a rising threat. Selecting a few of the most complex religious liberty issues, Shapiro oversimplifies them in an effort to blame a single enemy: an over-reaching government. While the government’s role deserves scrutiny, there is a fundamental problem with the essay. Religious liberty is not best understood or explained through an ideological lens that presumes that government is always the problem. Sometimes government infringes on religious liberty, but sometimes it also protects religious liberty by avoiding government sponsorship of religion, as well as by providing exemptions for religion.

Religious freedom is not just another policy issue that divides us along party lines. It is a fundamental constitutional value. Excessive partisanship and lack of nuance jeopardize it. Religious liberty is not easily simplified and should not be treated as belonging to one side of a bumper-sticker dichotomy, such as liberal vs. conservative; Democrat vs. Republican; religious vs. secular; or, in Shapiro’s view, government vs. the people. I sympathize with Shapiro’s description of the law as “muddled,” but that longstanding complaint is not easily resolved or aided by ridicule. I agree that diversity challenges our shared understanding, but it also stands as a testament to our success.

There are significant threats to religious liberty, and government gets in the way at times. But one of the biggest threats to our religious liberty is its politicization. Oversimplification, exaggeration, and myopia demean our legal tradition and make solutions harder to come by. In our law, religious freedom is protected in a distinct way—by limiting the government’s involvement in religion (no establishment) and by affirmatively providing accommodations and exemptions (free exercise). Both are essential and deserve bipartisan commitment. What if, instead of exaggerating threats of government overreach, we work to protect religious liberty for all, by keeping in mind the balance built into our first freedom that has served us well?

General and Specific Religious Exemptions Protect Free Exercise

Religious exemptions from general laws—whether constitutionally mandated or simply permissible as legislative accommodations—have long been part of our legal tradition to protect religious exercise. In general, exemptions take two forms: those that are specific to an anticipated religious liberty issue and those that provide a general standard for all religious liberty claims.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA) is an example of the general standard kind of exemption. It applies to all claims equally, including in contexts that were not anticipated when it became law. The Baptist Joint Committee led the charge to pass RFRA, has defended its standard, and in 2013 worked to commemorate its passage and evaluate its status.

RFRA was designed to protect the exercise of religion against substantial burdens from even incidental government actions. Its structure takes into account the balance between protecting religious exercise and serving other interests, including the rights of others. The key to RFRA’s bipartisan support was this strong standard, applicable to any claim. RFRA doesn’t guarantee any particular religious claim will succeed, and in fact many do not, but it benefits religious liberty by ensuring that each claim gets its day in court. Most successful RFRA claims are claims by individuals that have no detrimental impact on third parties.

Prior to Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) and other cases challenging the contraceptive mandate, RFRA was not well known, nor was it so widely criticized. Most people first learned about RFRA when it was invoked in the highly politicized context involving national health care, reproductive rights, and the status of corporations. In Hobby Lobby, the religious liberty claim prevailed, both because RFRA’s broad statutory language that applied to any “person” was interpreted to include closely held corporations, and because the government had already accommodated a similar objection for religious nonprofit corporations. In other words, the design of the contraceptive mandate showed that the government’s interest in providing the benefit to the employees could be met through secular insurance companies without imposing a substantial burden on Hobby Lobby.

The impact of Hobby Lobby, however, has been a growing suspicion about religious exemptions. The case raised alarms that an employer’s religious interests might always prevail over the rights of employees and that RFRA would be used to harm others, particularly in the commercial context. Many who defend the outcome in Hobby Lobby also recognize that RFRA has limits; otherwise the whole enterprise falls apart. In Zubik v. Burwell (2016), religious institutions used RFRA to challenge a specific accommodation designed for them and upheld in Hobby Lobby. Their claims went too far in asking for an absolute exemption, which threatened to deprive employees of a benefit paid for by secular insurance companies without cost to the religious institutions. Shapiro and others who argue for religious exemptions without recognizing limits for those claims make exemptions much less popular and less likely to be passed by legislatures.

Specific religious exemptions—those that are carefully crafted to address particular issues—are also important to protect religious liberty. Recently clashes between religious objectors and legal protections for LGBT people, particularly in the private marketplace, have provided fertile ground for discussion of specific exemptions but yielded few results. Again, the politicization of the issues has taken a toll on finding solutions.

Religious objectors and LGBT advocates are both fighting to protect what each claims is at the very core of their identities and most in need of preservation. Compromise, in the best of our democratic tradition, is possible if all sides are willing to come to the negotiating table. It may not be easy, but we’ve seen it happen in Utah (employment, housing, employee speech, access to marriage licenses) and in all the states that legislatively enacted same-sex marriage (reaffirming that clergy and/or houses of worship cannot be required to participate in any wedding ceremony).

Many city and state public accommodation laws already have some sort of religious exemption. The question is whether such an accommodation should apply in a for-profit commercial setting. Various proposals have been suggested that would permit such accommodations limited by the corporation size, availability of the goods and/or services in a reasonable proximity, the nature of the event, and the business owner’s involvement (e.g., whether a caterer attends the wedding ceremony or simply sells a pre-made cake off the rack). So far, however, the politicization of competing claims has made attempts to find solutions politically unworkable.

Special Treatment for Religion beyond Exemptions

Protecting free exercise, including through religious exemptions, is only one half of our religious liberty tradition. “No establishment” principles are less well understood, but they are key to ensuring religious freedom. Shapiro’s essay embraces religion’s special treatment on one side, but he ignores it on the other. Treating religion in unique ways when it comes to government funding is a valid, historic interest that serves religious liberty. The Supreme Court recognized this concern in Walz v. Tax Commission (1970) when it held “for the men who wrote the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment the ‘establishment’ of a religion connoted sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity.” The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment and corollary provisions in state constitutions protect against government-funded religion.

Baptists and other religious dissenters led the American fight for disestablishment. At the heart of their concerns was opposition to tax support for churches. Churches should be supported by the voluntary offerings of adherents, not the compulsory taxation of all citizens. Our colonial leaders knew that there would be no free exercise of religion if the government could force everyone to financially support government-approved churches.

The Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty continues to defend the no-aid to houses of worship principle, which remains vital for historical and practical reasons. It indisputably comes out of the founding era fights to disestablish religion and not anti-Catholic animus from the 19th century. In fact, 27 of the 39 states that have retained constitutional bans on direct funding of houses of worship have at least one provision based on Thomas Jefferson’s 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom that provided that no man shall be compelled to support “any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever.” This radical protection for individual conscience against government overreach remains important today. Religious liberty protections against government funding of religion—at the federal and state level—should not be dismissed as discrimination.

Conclusion

Government does not grant us freedom, but it is charged with protecting our freedoms. Religious liberty is protected in a distinct way in our constitutional tradition—both protecting the free exercise of religion and prohibiting the establishment of religion. Religious exemptions protect the free exercise of religion, as does the promise of no establishment. Shapiro does not address the importance of “no establishment” values—such as avoiding government funding of religion—which leads to the exaggerated claim that treating religion differently is simply discrimination harmful to religious liberty.

Time for One America, Not Two

To read Ilya Shapiro and David Gans, one would think there are two Americas. Many Americans, like Gans, applaud the developments that Shapiro and others lament: free contraceptives, laws protecting LGBT folks from discrimination, laws that separate church and state when it comes to public funds.

Other Americans share Shapiro’s intuition: blame for collisions between religion and the state properly lies with the growing administrative state and its control of “areas of life that we used to consider … not governmental.” Shapiro points to the silliness of “forc[ing] a Jewish printer to produce anti-Semitic flyers.” It follows, he argues, that reducing government would reduce conflicts.

But no one is shrinking government anytime soon. In fact, as Gans and Holly Hollman both point out, government is the protector of many religious minorities.

For his part, Gans wants to resolve questions over birth control and bakers with rights talk. He contends that allowing Hobby Lobby’s owners not to pay for emergency contraceptives that they believe end a human life authorizes “one party to impose their religious beliefs on another and extinguish their legal rights.” And so with the baker. Allowing a baker not to actively participate in a wedding she cannot assist with for religious reasons produces, he argues, “[t]he sting of prejudice from discrimination.” Gans invokes the specter of “a storeowner who claims that his religion commands racial discrimination” to say, in effect, “no exceptions allowed.”

Influential voices in America make the same mistake: One person’s rights, they say, come at another’s expense. Last year, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission said religious exemptions allow groups to “use the pretext of religious doctrines to discriminate.” Seventy-five religious leaders responded: all LGBT nondiscrimination laws, “including those narrowly crafted, threaten fundamental freedoms, and any ostensible protections for religious liberty, appended to such laws are inherently inadequate and unstable.”

Conflict Without Resolution

There are two problems with both accounts. First, neither recognizes that we all have to live together in the same space.

Second, continual litigation of these questions in the courts cannot tell us how to live together with dignity and respect. Even if the Supreme Court accepts the Masterpiece Cake Shop case knocking at its door, the Court is hamstrung in the answers it can give: the cake shop wins or the cake shop loses. The Court cannot refashion Colorado law so that a baker can live with integrity, while all couples are treated with dignity in the public square. In other words, constitutional decisions produce win-lose answers, not win-win results.

And don’t count on President Trump to end these clashes. The federal government cannot resolve the baker vs. couple question. Wedding vendors have been penalized under state and local laws. Title II, the federal public accommodations law, does not protect Americans from sex-based discrimination; it cannot be extended by agency decision to include sexual orientation or gender identity, as has happened with Title VII and Title IX.

Last week’s Executive Order on religious liberty did little more than end the “long ordeal” for the Little Sisters of the Poor, who asked to step aside entirely from the ACA’s contraceptive mandate. But neither Trump nor the EO addressed how Little Sisters’ employees will now fare. A draft EO from January 2017 suggested that the Sisters would be treated like the bishops—that is, like churches whose employees do not receive contraceptives under the ACA, from their employer or anyone else. Those employees get nothing. It remains to be seen whether Little Sisters’ employees will be boxed out of contraceptive coverage, too. (To be fair, churches are receiving the same treatment as Exxon, Visa, Pepsi, and other grandfathered employers.)

Focus on Solutions, Not Conflict

Meaningful solutions come from people of goodwill rolling up their sleeves and doing the hard work of crafting an approach that gives each of us the freedom to live and function in a society where others do not share our values.

It is easy to focus on conflicts over the Mandate and LGBT rights and overlook the lessons both have taught us for living together. In the Mandate context, President Obama treated with respect the concern voiced by religious universities and other nonprofits that they could not shoulder the new legal burden asked of them. He did not dismiss the concerns out-of-hand or force religious groups to violate their faith. Instead, he crafted an accommodation that gave contraceptives to women “free of charge, without co-pays and without hassles,” but shifted the duty elsewhere to pay for those valuable benefits.

In the LGBT rights context, Utah, the second most religious state in America, gave more rights to the full LGBT community than New York expressly gave that community. It did so by assuring religious groups and believers that gay rights would not wash out the faith character of faith communities. It drew careful statutory lines that permitted both communities to be who they are. Months before Kim Davis loudly proclaimed her religious conscience prevented her office from serving Kentucky’s citizens, Utah devised a new mechanism to guarantee seamless access to marriage for everyone—gay, straight, Black or White. No one was turned aside or humiliated, no one was forced from their jobs for their religious convictions. That careful balancing of interests comes from legislatures, not courts.

Both sides really have no choice other than to engage in the hard project of living together.

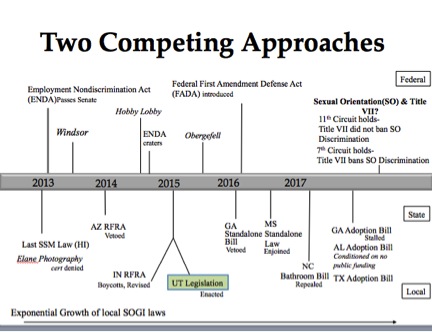

As this figure shows, gay couples can marry everywhere in the United States, but in 31 states, they cannot be assured of having a rehearsal dinner at their favorite restaurant.

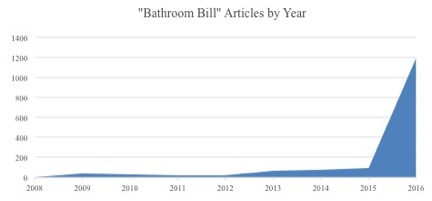

Moreover, there has been no new state LGBT nondiscrimination law covering public accommodations in America since 2007 (although some states have incrementally extended protections). Not coincidentally, 2007 is the year when opponents of LGBT nondiscrimination laws started tagging those laws as “bathroom bills.”

To be clear, bathroom-of-one’s-birth bills are not religious liberty protections, as Professor Douglas Laycock notes. As North Carolina’s own experts emphasized, “transgender individuals are not the source of [any] threat.” The behavior of rapists and child molesters is the issue. However, magnifying fears has become the tactic of choice to oppose all nondiscrimination protections for LGBT people, whether in public accommodations, hiring, or housing.

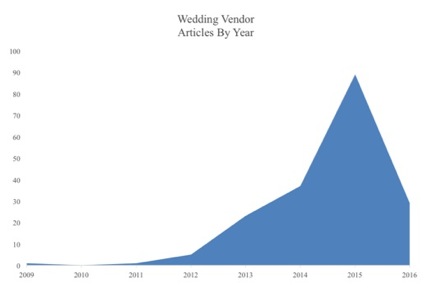

More and more media attention is consumed by wedding photographers, bakers, and florists being penalized or litigated out of existence, making possible compromise seem farther out of reach.

Overlooked is the fact that the crushing outcomes visited upon wedding service providers result from laws written without marriage in mind. Indeed, the relevant laws all pre-date marriage equality.

These dated laws treat every act as if the owner said “get the hell out of my business.” But it does not need to be this way. We can write laws that treat all customers with respect, while keeping small religious wedding vendors in business.

Everyone has a vested interest in finding such solutions.

Still, many who care deeply about religious liberty fear that protecting LGBT people from discrimination means religious people necessarily lose. Utah shows otherwise. It has more religious liberty protections around marriage than any other state—it accomplished that by giving rights, not blocking them.

As important, firing people for being gay is unjust, and protecting our neighbors from unjust treatment is a shared religious value. Libertarians who read this Journal surely believe that all Americans should be able to compete in the marketplace based on their merit—to support their families and have a chance at the good life. That, after all, is the meaning of the American dream.

If not these reasons, then self-interest should make religious communities take affirmative steps to protect the rights of others. The fight-tooth-and-nail approach simply does not work.

Let’s review the track record: stand-alone measures giving religious believers an unfettered right to affirm views of sexuality blessed by Mississippi are enjoined; a stand-alone, inartful religious conscience bill sparked boycotts and was vetoed, in Georgia. North Carolina’s bathroom law was an unmitigated disaster for the state, costing $3.7 Billion; it was repealed. And state Religious Freedom Restoration Acts or RFRAs, misunderstood by religious believers “as needed to stave off gay rights,” have become toxic and untenable, as Arizona and Indiana show.

It is a fairytale to think doing nothing will suffice. Sixty percent of the nation lives under a state or municipal law protecting the LGBT community—often without nuanced consideration for houses of worship or the needs of faith communities.

It is time to put the two Americas to rest and start living as one people.

The Conversation

Can’t We All Just Get Along?

If you read the first two responses to my essay, you would think that I simply missed the boat, or at least the second half of the religious liberty question, by not discussing the Establishment Clause. And indeed, the word “establishment” doesn’t appear in my contribution, in large part because modern America simply doesn’t face a threat of “establishing” state religions of the kind that caused the Framers to write this provision into the First Amendment (unless you count the post-modern “religions” of environmentalism and identitarianism, but that’s a subject for another symposium).

I’m sorry, but the fate of the Republic doesn’t turn on the issue of what kind of Ten Commandments monument you can put up and where. (For the record, an old monument that’s outside is okay, but a newer display that’s inside a government building is not.) Nor am I much interested in debating whether, given that public funds can buy maps for parochial schools but not books, such funds can buy atlases. Or what kind of after-hours student-organized prayer at public schools constitutes state endorsement of religion. This may be my agnosticism showing, or perhaps my philosophical impatience, but all that’s small beer.

Moreover, I actually do touch on public funding of religious organizations in the way that the Trinity Lutheran case raises the issue—in the context of eligibility for generally available state programs. While the specific facts there concern subsidies for rubber playground surfaces, the issue most frequently arises in the context of school choice, and the way that many state statutes that mandate “no aid” to religion are used not just to prevent tax-supported churches—with which I have no quibble—but to hobble parents’ abilities to seek educational opportunities for their children. (These Blaine Amendments spread in the late 19th century not to further separate church and state, but to harm minority sects, especially Catholics.) I’d be happy to discuss that sort of thing further, but I sense that’s not where my interlocutors were going.

Instead, David Gans raises “President Donald Trump’s crusade against Muslims,” which is a lackadaisical crusade indeed given that its only manifestation is a regulation of entry into the country by people from six majority-Muslim countries. This may be good or bad policy—it’s unclear whether vetting procedures in the targeted countries represent the biggest weakness in our border defenses, and don’t (uncovered) Pakistan and Saudi Arabia produce more terrorists?—but the challenges to the “travel ban” will rise or fall on whether Congress granted the president authority to make nationality-based restrictions under the immigration laws in the name of national security. Even ACLU lawyers concede that the executive order would’ve been fine if any other president had issued it. This is not a burning constitutional issue—let alone one concerning the Establishment Clause. Candidate Trump may have said many things, but his administration hasn’t done a single thing that hurts the religious liberty of Muslims in America.

K. Hollyn Hollman makes a more interesting point, that “[r]eligious freedom is not just another policy issue that divides us along party lines” and indeed that “one of the biggest threats to our religious liberty is politicization.” I couldn’t agree more with that, or at least with the idea that religious liberty shouldn’t be a partisan or political issue. And yet it has so become in recent years, as have other matters of previously uncontroversial concern, ranging from support of the only democracy in the Middle East to biotechnological progress in agriculture. Sigh.

And so we get to Robin Fretwell Wilson’s hopeful missive and the suggestion that “solutions come from people of goodwill rolling up their sleeves and doing the hard work of crafting an approach that gives each of us the freedom to live and function in a society where others do not share our values.” That’s certainly true, but I’m not sure that compromise is achievable when one side insists that every last butcher, baker, and candlestick-maker kowtow to prevailing ideological diktats. Social norms and basic manners ought to resolve most of these conflicts—which facilities did transgender people use before either SOGI laws or “bathroom bills”?—but alas our litigious age forces legislation into every nook and cranny of interpersonal relations, eradicating the “play in the joints” of our public treatment of religion.

Religion shouldn’t be a trump card in our debates on culture or public policy, but the solution to the problem of religious special treatment is not, as critics of religious businesses argue, for government to deny exemptions to all such that all are equally coerced. Instead, the approach consistent with the American principle that the state exists to secure freedom is for government to recognize the right of all individuals to act according to their consciences.

We should accept that in a large, pluralistic society, we’re simply going to have disagreements about many important values. But there’s no need to force someone to do something, to bend to your will, unless there’s literally no other way of achieving a truly essential goal.

Live and let live. Can’t we all just get along?

The Establishment Clause Still Matters. Here’s Why.

Ilya Shapiro doubles down on his one-sided view of the Constitution’s protection of religious liberty, turning a blind eye to the Establishment Clause and its structural guarantee of religious neutrality by the government. He basically reads the Establishment Clause right out of the First Amendment.

Shapiro justifies his disregard of the Establishment Clause on the basis that “modern America simply doesn’t face a threat of ‘establishing’ state religions of the kind that caused the Framers to write this provision into the First Amendment.” On this view, the Establishment Clause was once important but has been consigned to the dustbin of history.

The problem is that Shapiro ignores what the First Amendment actually says. It does not simply forbid the establishment of an official state-approved religion. Its language is broader, prohibiting the making of any “law respecting the establishment of religion.” As the Supreme Court has recognized, “[t]he very language of the Establishment Clause represented a significant departure from early drafts that merely prohibited a single national religion.” As written, the Establishment Clause ensures that, in the words of James Madison, “[t]he Religion … of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man,” preventing efforts to “degrade[] from the equal rank of Citizens all those whose opinions in Religion do not bend to those of the Legislative authority.” That is why the Supreme Court has held that “[t]he clearest command of the Establishment Clause is that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.” Far from being a dead letter, the Establishment Clause’s assurance of religious equality provides a crucial protection of religious liberty, particularly in this day and age.

Shapiro is equally dismissive of perhaps the biggest religious liberty question of the day: Donald Trump’s effort to make good on his campaign promise to enact a “Muslim ban,” which has been temporarily blocked by the courts on the grounds that Trump’s executive order likely violates the Establishment Clause. Yet according to Shapiro, “[t]his is not a burning constitutional issue—let alone one concerning the Establishment Clause.”

Shapiro calls Trump’s effort “lackadaisical,” claiming that “his administration hasn’t done a single thing that hurts the religious liberty of Muslims in America.” Once again, Shapiro’s crabbed arguments have no footing in the real world. Far from being narrow, Trump’s Muslim travel ban, even as revised, affects millions of people from six Muslim-majority nations. As Fourth Circuit Judge Barbara Kennan observed during oral argument in IRAP v. Trump, “You’re talking about 82 million people.” The travel ban prevents U.S. citizens and others within the United States from reuniting with families and stigmatizes Muslims as a danger to our country. Trump’s sweeping executive order writes religious discrimination into our immigration laws—a frontal assault to the religious freedom our Constitution promises to all, regardless of their religious faith. Whatever power the President has under immigration laws—and there is no doubt he has considerable leeway—he cannot erase the Constitution’s commands. A religious immigration test designed to denigrate those who believe in Islam cannot be squared with the Establishment Clause.

Our Constitution’s Religion Clauses establish a firm foundation for religious liberty and equality in America, ensuring a government that “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” You don’t defend the Religion Clauses by trashing one of them.

Religious Freedom Beyond the First Amendment

I appreciate Ilya Shapiro’s plea for us all to get along. The most productive way to do so when it comes to religious liberty is by affirming the values of both of the First Amendment’s religion clauses. It is easy and all too common to undervalue the Establishment Clause and its unique and essential role in protecting the religious freedom we enjoy. That is particularly true when one skims the surface of disputes over government-sponsored Ten Commandments displays or when one is not invested in providing public schools that serve all children without regard to religion. The principles of “no establishment” and “free exercise,” however, are two sides of the same coin and ensure that the government’s role in religion is limited. Those principles are necessary to move in the direction of a live-and-let-live attitude toward religion that Shapiro embraces.

David Gans’ strong defense of the Establishment Clause in our constitutional order appropriately broadens the lens and advances the conversation. The state and federal “no establishment” constitutional provisions remind the government that questions of when, where, how, and what to worship are outside its realm of competency. If a church or synagogue wants to erect a Ten Commandments monument, it should have every right to do so, but it may not demand that the government use taxpayer dollars and property to do it. The role of these constitutional provisions in debates over school vouchers is important, not because they hobble anything but because they are part of what keeps government from interfering in religion.

Interestingly, Shapiro dismisses the religious liberty concerns raised by President Donald Trump’s Executive Orders on immigration partly because they aren’t crafted well for the purpose candidate Trump asserted. The connection between the candidate’s rhetoric and the president’s actions is just one of the many legal issues that will be examined, along with the impact on Muslims cited by Gans. Regardless of the outcome of the constitutional claims in court, however, religious liberty has been harmed. It takes more than just legal protection to ensure that faith can be freely practiced, and anti-Muslim rhetoric, especially coming from our leaders, denigrates religious liberty for all. Just as in other contexts where the way we talk about religious liberty matters, there are significant consequences when we lose sight of the principle that all religions should be treated the same under the law.

Not All Government Expenditures Are a Subsidy to Religion

Ilya Shapiro and K. Hollyn Hollman push us to think more carefully about when “no establishment” values slip over from preventing government actions with a “predominant purpose of advancing religion” into singling out religion for special disadvantage. In one sense, Trinity Lutheran is an easy case.

How can a state commit funds to make playgrounds safer from the predictable falls and scrapes children experience, but withhold that good from children who attend religious schools or play on their playgrounds? As Justice Elena Kagan framed the issue during oral argument, “the question is whether some people can be disentitled from applying to that program and from receiving that money if they are qualified based on other completely nonreligious attributes, and they’re disqualified solely because they are a religious institution doing religious things.” One would hope the Court rejects a vision of America where religious people alone are disqualified from public benefits available to everyone else.

But as Shapiro notes, this case is an outlier. It is not so often that governments adopt public benefit programs that serve everyone except the religious—although “Blaine Amendments” disqualifying religious recipients remain in 37 states and should be discarded. And it is not so often the governments choose to display the Ten Commandments or creches at city hall, provoking Establishment Clause challenges.

Far more prevalent are government programs that support human flourishing, like vouchers for secondary education, school lunch programs, state college grants, funding for scientific research, etc. Religious entities shoulder social services and other functions on a staggering scale, by one estimate $9.2 billion in social services alone. Add to this an estimated 7.6 million volunteers from congregations, and society has a selfish interest in religious groups continuing to do good works.

A flashpoint has ignited around public funding: if you take public money, you play by public rules. Here’s the rub: society often devotes resources to achieve a specific end, like educating its citizens.

Sometimes, a student—or her family—is the one who chooses where to spend those public dollars. This is no more a subsidy of religious colleges or schools than providing rubberized surfaces on all playgrounds, including religious ones. Religious schools are the incidental beneficiaries of monies that change the arc of a student’s life.

One in four colleges in the United States—more than 1000—are religiously affiliated. Many train people to teach the faith, but most are places where students can gain “an education based on biblical faith in order to develop men and women in intellectual maturity, wisdom, and Christian faith who are committed to serving the church, community, and world.”

These schools are religious in more than name alone. Students learn science, math, civics, and other subjects, true, but the university is also concerned with “spiritual formation.” Religious colleges have a pastoral function and relationship to all their students, including their LGBT students.

But religious schools are an important bulkhead in a sea of change. In recent years, people of faith have found themselves in a literal minority, at least as to certain beliefs. Transmitting faith in a conscious way has become an existential endeavor. In Strangers in a Strange Land: Living the Catholic Faith in a Post-Christian World, Archbishop Charles Chaput describes this moment as “a time of transition” in which cultural trends are taking shape, some of which “are distinctly unfriendly to the way Christians live their faith.” Echoing Chaput, Rod Dreher, author of the bestselling The Benedict Option, says Christians must “hold on even more strongly to the truths of the faith because there will be even more pressure in the public square to conform to this post-Christian orthodoxy, to abandon our faith, to apostatize.”

In 2016, California Senator Ricardo Lara introduced a bill to subject any post-secondary educational institution (other than seminaries), which avails itself of the exemption given it under the federal education law known as Title IX, to liability for sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination. This would have meant that the schools could be sued, but worse, Cal Grant dollars could not be spent at schools unless they yielded on their federally protected religious convictions around sexual orientation and the nature of gender. Religious exemptions were seen as nothing more than “a loophole that gave faith-based institutions a ‘license to discriminate’ against LGBT students.”

Lara was concerned that students would be caught unawares if “their sexual orientation or gender identity did not align with the universities’ ‘values.’’ This concern was not unfounded. Although no college seems to expressly refuse admission to LGBT students, in practice some bar “homosexual acts.” Far better to institute equally applicable conduct policies—e.g., all students should be chaste, gay or straight, without prohibiting gay sexuality alone. In some especially poignant cases, students have enrolled in a college only later to fall in love with a person of the same sex, resulting in dismissal.

For their part, religious groups feared “Senate Bill 1146 [would] result in its own form of discrimination by stigmatizing and coercively punishing religious beliefs that disagree on contested matters related to human sexuality.” The overarching fear was the “California bill would erase religious schools.” Stakeholders raised $350,000 and “flooded” Assembly members’ districts with mailers.

Then something remarkable happened: the author of a parallel bill and the president of Biola University, a religious college in California, “decided to talk to each other.” Assembly member Evan Low and President Barry Corey listened to one another and took each others’ concerns seriously.

Rather than the “new normal of division, incivility, and hate,” the two found areas of common interest—like supporting first-generation and minority students to succeed in college. Governor Brown ultimately signed into law a measure that increased transparency about a school’s values.

Perhaps one ground on which agreement can be found going forward is admissions. Despite the romanticism of the Benedict option, students after college will not withdraw behind a wall to toil indefinitely—they will enter, and should be prepared for, the world and all its differences. Even within islands of believers, the community is stronger for being more inclusive, including of LGBT students. Exclusion defeats the university’s own educational mission, harming both those excluded and the university community as a whole.

K. Hollyn Hollman lauds “compromise, in the best of our democratic tradition, [when] all sides are willing to come to the negotiating table.” She is right that the “politicization of competing claims” makes this difficult. A first step in reaching compromise is not to treat all money that flows from government as a subsidy to religion.

Context Matters as the Conversation Continues

As was evident from the first essay, the topic of religious liberty today brings to mind a number of challenges. It will take time to work through conflicts that arise as we navigate new waters of legal and cultural changes with regard to LGBT rights. It will also take hard work to get to a mutual understanding of what is at stake for all, including in contexts far beyond wedding vendors, as Robin Fretwell Wilson highlights in her last post.

By introducing the topic of government funding of religious institutions, Wilson moves the conversation to a new level of complexity. How our laws protect religious liberty depends on the context. The Trinity Lutheran Church case is different from cases about school vouchers or social services.

Religious people and religiously affiliated institutions have long been involved in government programs through various partnerships, carefully designed in ways to avoid subsidizing religion. Even the attorney for Trinity Lutheran Church conceded to Justice Elena Kagan that states are entitled to refuse to fund religious activities. The question is whether a state can take preventative measures to avoid unconstitutionally paying for religious activity by prohibiting the use of tax dollars for capital improvements to church property. Churches after all are unique religious institutions formed for the purpose of religious expression and exercise. They may or may not involve ministries that provide secular social services (food pantry, homeless outreach, medical clinic, education, etc.) performed by various religiously affiliated institutions.

Regardless of whether Trinity Lutheran Church proves to be “an easy case,” as Wilson describes it, state constitutions are part of the legal tradition that protects religious freedom. Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted during oral arguments that “We seem to be confusing money with religious practice.” The State of Missouri is not deciding how churches use their property. It is not forcing Trinity Lutheran Church to have a playground, prohibiting it from having one, or dictating how the church should use it; it is simply refusing to pay for its resurfacing. An important aspect of the American tradition of religious liberty recognizes that government often protects religion by staying out of it.

Despite our diverse perspectives on specific issues, it seems we can agree that religious liberty is a fundamental constitutional value, and as David Gans explains, a founding principle, worthy of a deeper conversation. Our religious liberty tradition of “free exercise” and “no establishment” has served our country well and stood the test of time through careful tending. We may not agree on all of the outcomes of specific disputes, but we should recognize the value of important safeguards that have protected against government-sponsored religion and have protected our religious institutions.