About this Issue

Philosophers since Plato have known that some choice about urban planning can only be made once — at a city’s founding. Getting the founding right therefore matters a great deal for a city’s success. Locking in favorable decisions about individual liberty and voluntary cooperation may require steps that begin before any city has been built at all.

Nor is this just utopian speculation. Special economic zones have played a key role in China’s economic liberalization, and they are arguably one reason why China has prospered so much in recent decades. Can this model be replicated elsewhere? Our lead essayist this month, Dr. Mark Lutter, says yes, and he calls on governments worldwide to embrace regional and local experiments in liberalization. Not everyone is so optimistic, however. The inherently inegalitarian nature of these projects may be of potential concern to almost anyone, and a special economic or legal regime may even represent a worsening of local conditions in absolute terms. To discuss these questions, we have recruited Dr. Lant Pritchett of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government; Prof. Sarah Moser of McGill University; and Prof. Tom W. Bell of Chapman University. Each will write a response to Lutter, and all will participate in a conversation through the end of the month. Comments are open as well, and we welcome readers’ feedback.

Lead Essay

Local Governments Are Changing the World

The greatest humanitarian miracle in the postwar era is China. The World Bank estimates that economic growth in China has lifted approximately 800 million people out of poverty since 1980. Chinese growth was largely driven through strategic economic reforms implemented through special economic zones. Economic reforms were impossible at a national level; however, by testing them in relative backwaters, the demonstrated success led to replication throughout the country.

Shenzhen, which was a fishing village of 30,000 residents in 1980, epitomizes the success of Chinese special economic zones. In 1981, the first year of the city’s special status, it attracted over 50% of all foreign direct investment in China, which at the time had a population of 993 million. Now, the greater metropolitan area of Shenzhen has a population of 23 million. In 2016, Wired Magazine dubbed it the “Silicon Valley of Hardware.”

The initial success of Shenzhen led to China replicating their special economic zone strategy of reforms. Within four years, the success of the SEZs became clear. China opened its economy, identifying 14 coastal cities to extend similar SEZ policies to. The following year, such policies were applied to cities in the Pearl River Delta, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Min Delta. Even after the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, SEZ policies continued to advance, with Shanghai gaining the Pudong New District in 1990. In 1992, all capitals of provinces and autonomous regions in the interior gained special status. By this time, special economic zones were no longer as special, as their policies had spread throughout China.

Despite China’s success, no other country, with the exception of Dubai (ok, it’s not really a country), has generated sustained economic growth through SEZs. India, for example, passed SEZ legislation in 2005. In theory the legislation was modeled on China’s. In practice, though, it was piecemeal, and didn’t lead to substantive changes.

The Innovative Governance Movement

The particular reasons why China’s special economic zone success was never replicated elsewhere is beyond the scope of this essay. However, the last ten years has seen a surge of interest in innovative governance. The innovative governance movement has combined an academic as well as popular interest in Shenzhen and China’s special economic zones, relating their success to what might be broadly termed charter cities, semi-autonomous, or fully autonomous cities.

The innovative governance movement is interested in improving governance via the creation of new jurisdictions with significant degrees of autonomy. These new jurisdictions could import successful institutions to create the conditions for catch up growth. Or the new jurisdictions could experiment with new forms of governance, to push the frontier. The overarching thesis of innovative governance is that the existing equilibrium of political units is overly resistant to change, and small, new jurisdictions, particularly on greenfield sites, are an effective mechanism to institutional improvements.

The modern innovative governance movement was launched ten years ago when Patri Friedman and Wayne Gramlich created the Seasteading Institute. Critical of the lack of success of traditional libertarian attempts at social change, the Seasteading Institute argued that new societies, “seasteads,” could be created in international waters. Seasteads would provide a blank slate for institutional innovation and experimentation. Successful models of governance could attract new residents, while unsuccessful ones would fail. This iterative, evolutionary process of governance improvements could help push the frontier of the optimal type of government.

In 2009, one year later, Paul Romer gave his famous TED talk on charter cities. Unlike the Seasteading Institute, which focused on pushing the institutional frontier, Romer focused on improving institutions in low- and middle-income countries. He argued that a high-income country, Canada for example, could act as a guarantor for a new city in a low-income country, Haiti for example, effectively importing Canadian institutions to Haiti. Later Romer seemingly expanded the definition of charter cities to not require a guarantor country.

Related nonprofits proliferated in the following years. The Charter Cities Institute, later rebranded as the Startup Cities Institute, launched out of Universidad Francisco Marroquin, only to fold several years later. Enterprise Cities, run by trade lawyer Shanker Singham, was based in Babson College. Refugee Cities was launched to apply these ideas to the refugee crisis.

More interesting than the discussion has been the projects. Romer took the lead, meeting with the President of Madagascar in December 2008. However, while Romer was making progress with the president, political unrest grew because of a planned 99-year lease of a Connecticut-sized tract of land to Daewoo, a South Korean corporation. The political unrest turned to protests, which turned to riots. Guards opened fire on marchers outside of the Presidential Palace, killing 28 people, soon after which the president resigned.

The next potential project was in Honduras. Inspired by Romer, in 2011 Honduras passed the RED legislation, which allowed the creation of charter cities. In September 2012, Romer publicly unaffiliated himself with Honduras. The Transparency Commission, which he had been promised a role in, was never legally created, and a Honduran agency signed a memorandum of understanding with a private company interested in creating a charter city. In October 2012, the Honduran Supreme Court ruled against the RED legislation.

Charter city hopes for Honduras, however, refused to die. In 2013, Honduras passed the ZEDE legislation, aimed at creating a framework within which charter cities could be created, as well as pass constitutional muster. The ZEDE legislation did pass constitutional muster, though the justices who had voted against the RED legislation had been removed from the Supreme Court. Since then, no projects in Honduras have been approved, at least publicly. However, there remains continued interest in Honduras (see here, here, and here) as the law, as it is written, creates tremendous potential opportunity.

The last relevant project is Blue Frontiers, a for-profit spinoff of the Seasteading Institute. In 2017 the Seasteading Institute signed a memorandum of understanding with French Polynesia to create floating islands in protected waters. In return for the investment, the government of French Polynesia would create a seazone, a special economic zone on the water, such that the seastead could compete via regulatory arbitrage.

Landscape

Historically, the innovative governance movement has been heavily influenced, and arguably led, by techno-libertarians, with Romer being the obvious exception. This is beginning to change. However, while the techno-libertarian attitude was arguably important for the vision, it hampered the development of more practical capacities necessary for the creation of charter cities.

Silicon Valley is a world of amateurs. To launch a startup, just lock three talented programmers in a basement for six months and they’ll emerge with a minimum viable product. Facebook’s old motto, “Move fast and break things” is reflective of Silicon Valley culture broadly. Such an approach is not practical for charter cities.

First, charter cities are both political and business projects. They are political projects in the sense that they require legislative approval from a host country to create legal autonomy, as well as continued tacit approval of such autonomy. They are business projects as they need hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars of investment to be economically viable. Politicians are generally reluctant to break things or empower others to do so. Similarly, required centi-million dollar plus investments for minimum viable products requires a degree of expertise.

Luckily, things are changing, making charter cities more viable than they were ten years ago. A handful of influential groups are beginning to think about charter cities. That said, they’re coming at it from different angles, and few have the full vision. However, with proper coordination, it’s possible to rapidly, within 2 to 3 years, create the environment within which several charter city projects can be launched. Let’s consider some of the perspectives at hand.

Economists: Most development economists are sympathetic to charter cities. While some are strongly critical, there is nevertheless a general sense that charter cities are an idea worth trying. The downside is that economists don’t get career points for discussing charter cities. For example, Romer, who is frequently listed as a contender for the Nobel Prize, gave a TED talk on charter cities rather than publishing an academic article.

Silicon Valley: Silicon Valley is interested in cities. YCombinator made a big splash about building a city, though it was later toned down to research. Seasteading is big enough to be made fun of on HBO’s Silicon Valley. Multiple unicorn founders have told me they are building up a war chest such that they can build a city when they exit.

Humanitarians: While the refugee crisis has dropped out of the news recently, there remains interest in improving refugee camps via special economic zones and creating charter cities as a mechanism for economic development to lower the demand for emigration. The Jordan Compact gives aid and favorable grants to Jordan in exchange for work rights for refugees and increasing refugee participation in special economic zones. Kilian Kleinschmidt, who formerly ran the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan and is on the Board of Advisers of my nonprofit, the Center for Innovative Governance Research, argues for special development zones for migrants. And of course, there is the aforementioned nonprofit Refugee Cities. Michael Castle-Miller is developing the legal and institutional frameworks for these charter cities via his teams at Politas Consulting.

New-city projects: There are dozens of new city projects around the world. These new city projects are real estate plays, building satellite cities of 50,000 or more residents. Investments in these new cities is rarely under $1 billion. Nkwashi, a new city project in Zambia, is one of my favorite examples. Mwiya Musokotwane, the CEO, is on the Board of Advisers for the Center for Innovative Governance Research.

Some of the new city projects are beginning to think about governance, which is a natural path as their revenues are based on land values.

A final interesting development, which is hard to place or categorize, is that Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the former Prime Minister of Denmark and former Secretary General of NATO, also has an interest in charter cities and special economic zones. He recently launched a new foundation, the Alliance of Democracies Foundation. One of the key initiatives of the Foundation is Expeditionary Economics, which is focusing, as previously mentioned, on charter cities and special economic zones.

The Future of Innovative Governance

Innovative governance is happening; governments are increasingly willing to grant autonomy for economic growth. Combine that with the profits that result from building cities; land values in Chicago, for example, increased over 30,000-fold the first hundred years of its existence, and the potential of innovative governance becomes clear. Innovative governance projects can be split into three categories, government-led, real estate led, and entrepreneurial.

Government-led projects are the most developed. By definition, they are able to overcome the political barriers. The Dubai International Financial Center, for example, is an excellent case study in how to import common law. Dubai realized that Islamic law is not particularly conducive to the modern banking system, so they hired a British judge to oversee the importation of common law. Abu Dhabi recently followed suit with the Abu Dhabi Global Market.

Neom is arguably the most interesting innovative governance project. It is a Saudi led project, on Saudi, Jordanian, and Egyptian land, with a projected price tag of $500 billion. Promotional materials suggest substantial, if not complete, autonomy in commercial law. The other potential government-led project on the horizon is a refugee city, likely in the Middle East or North Africa. It has attracted the interest of people as diverse as Gordon Brown, who called for economic zones for refugees, to George Soros, who also called for economic zones for refugees.

The Jordan Compact is perhaps the closest thing to the internationally led vision. It brings together grants, low interest loans, and tariff breaks for giving refugees work permits and integrating them into under-capacity special economic zones. Unfortunately, the early signs suggest it isn’t living up to its potential. There has been limited discussion of a grander vision of a charter city. For example Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry has called for Europe to build and protect a ‘Hong Kong’ in Syria.

New-city projects, as mentioned above, are likely to prompt some thinking about improving governance. They’ll tend to be risk averse, however, as they view governance as a non-vital bonus to their real estate project. However, as many of these projects are sufficiently large, many of the developers have good relationships with government officials who could help create a special economic zone for the new city.

The third type of project is entrepreneurial. Blue Frontiers falls into this category, and there are a handful of others which are not yet public. Entrepreneurial projects tend to have the biggest dreams and governance innovations, but the also have greater risks of failure.

Conclusion

As charter cities and other innovative governance projects become increasingly viable, it becomes important for interested groups to coordinate with one another. Conversations for too long have remained siloed. Lessons learned by one group aren’t effectively transmitted to other groups, limiting the impact of the ideas.

Additional research is necessary. While there has been promising interest in recent years, given the role charter cities and innovative governance projects are going to play in the twenty-first century, the current state of knowledge remains inadequate. Foundational questions — such as the economic, legal, and moral case for charter cities and innovative governance — need strengthening. Similarly, practical questions, such as the impact of improvements in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index on urban land values, and the best practices in creating a legal system from scratch, can help guide charter cities and other innovative governance projects.

It is important to continue to develop the ecosystem for innovative governance. As China demonstrated, hundreds of millions of people can be lifted out of poverty through a strategy of zone-based economic reforms. There is an opportunity to replicate that strategy. It should be taken full advantage of.

Response Essays

The Future Is Already Here

In Mark Lutter’s lead essay, “Local Governments Are Changing the World,” he provides an interesting and timely overview of a wide array of innovative urban ideas and projects built from scratch, including special economic zones, charter cities, seasteading, new cities, and other jurisdictions with varying degrees of autonomy.

His essay chronicles decades of libertarian failure to get projects off the ground, which reads as a forceful indictment against the capacity of grass roots libertarians to become city-builders. As Lutter points out, startup societies have a unique knack of getting kicked out of the places where they are trying to build and have struggled to apply a Burning Man / Silicon Valley / libertarian ethos to real-world contexts in their city-building endeavors.

As Lutter outlines, projects from Operation Atlantis, seasteading, and charter cities, to attempts in Madagascar, Honduras, and French Polynesia have failed to materialize. He neglects to mention that some of the luminaries pulled momentarily into the orbit of the startup cities world have since departed, notably Peter Thiel and Paul Romer.

In stark contrast, Lutter goes on to summarize some of the innovative urban spaces underway in China, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The main difference is that the projects materializing are driven by strong, authoritarian states and corporations who have the connections, financial backing, negotiating skills, technical expertise, and organizational capacity to pull off engineering feats and governance innovations that were unimaginable ten years ago, and that remain far out of reach for American startup cities movements.

The new types of city building, governance, and urbanization of the ocean that startup societies describe are already underway. For better or for worse, government regulations are being dismantled or circumvented in specialized zones in dozens of countries at an unprecedented scale. Autonomous and semi-autonomous zones to which host states have largely conceded sovereignty are popping up in such places as east Africa, the Arab peninsula, and southeast Asia.

The American startup cities crowd is dreaming about a future that is already here.

So why are startup cities folks not talking about these projects? The invisibility of these projects is partly due to the fact that they are very new and are located far from the United States, largely in non-English-speaking places. But they are perhaps also invisible due to the unfamiliar faces at the helm. It is not American men at the forefront of this radical experimentation – current projects are conceived, financed, and executed by Chinese and other Asians, Arabs, and Africans.

What needs further teasing apart among startup cities advocates is how they philosophically align with the proliferation of these new autonomous zones. Lutter does not make any distinction between or hierarchy among projects he surveys, perhaps because the brief format did not allow for this level of elaboration.

However, aside from the many failed startup city projects, there is a wide range of negative impacts that deserve careful study. There is growing evidence that the collateral damage produced by many projects is severe and unacceptable to many: there are ecological disasters; many have demonstrated little respect for human rights, dignity, or lives; they are not accountable to any public, and they are sites of unprecedented corruption. There is a consistent disregard for legally protected tribal and indigenous land. They are certainly zones of experimentation with new forms of governance and unique levels of autonomy, but at what cost and to whom?

If the libertarian position is that you can’t make a startup city omelette without breaking a few human rights and ecology eggs, their projects may continue to be thwarted by angry and rightfully suspicious citizens.

The pockets of autonomous zones are proliferating, yet like any utopian idea their fortunes and fates are still tied to the rest of the world. They rely on governments to invest in research, telecommunications, transportation networks, security, and stable financial markets.

Lutter is right to point out that startup cities are inherently both political and business endeavors. Startup city advocates tend to gloss over politics and the troubling colonial dimension of their projects. Libertarians may not feel like colonial entities, yet it sends a disturbing message to accept tracts of land from the corrupt and undemocratic leadership of other countries, and then proceed to reject their laws and social norms. This type of acquisition of foreign territory, also called “land grabbing,” is broadly perceived as a provocation that will continue to enrage and mobilize citizens around the world.

Chinese companies and the Chinese state have been the most high profile in acquiring land and sea rights in foreign countries where they construct strategically located (semi-)autonomous zones. Forest City, the largest Chinese investment outside of China, is a new private enclave being built by a Chinese company for 700,000 on four artificial islands in the territorial waters of Malaysia. The company has negotiated major concessions of sovereignty: no Malaysian police or military are allowed, freehold property can be sold, and Malaysian law does not apply. It has faced sharp criticism by the former leader of the opposition-turned-Prime Minister, who attacked the selling of land to foreigners, arguing it was a form of colonialism.

Other experimental urban enclaves are being created in Saudi Arabia, Zanzibar, Ecuador, Oman, and more. These projects have varying levels of autonomy and special incentives and more liberal rules on personal freedom than the rest of the country, often governed not by national law but by a city charter.

It is a wild west out there without any semblance of the checks and balances, regulations, and moderating effects that responsible government provides.

China: A Flawed Model for Startup Cities

In his essay, Lutter points to China as the greatest economic and humanitarian miracle in the post–World War II era. He attributes this success to China’s Special Economic Zones (SEZ), and proceeds to connect China’s success to the libertarian dream of creating new cities from scratch.

Lutter states that the particular reasons why China’s special economic zone success has never been replicated elsewhere is “beyond the scope of this essay.” I suggest that if they are to be claimed as a model for startup cities, China’s SEZs require careful and rigorous study by libertarians, seasteaders, advocates of charter cities, and by anyone else looking to China for inspiration.

While not to deny China’s extraordinary economic growth since the reforms of 1979, looking to China as a model is cherry picking of the highest order, and flawed for a number of reasons.

First, context matters, and the success of Chinese SEZs cannot be celebrated in isolation from broader demographic factors and economic history. China has controlled between 25% and 35% of the global economy for much of recorded history, except for a brief period roughly between the Opium Wars and Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms.

Second, after China shut its doors in 1949, the capitalist world was eager for access to the world’s largest market. The United States was so desperate to establish ties with China that it swallowed its pride and ended its diplomatic relationship with Taiwan, a democracy that it had supported since China’s communist revolution ended in 1949. This external demand for trade is unique to China.

Third, Lutter refers to the location of Shenzhen, China’s first SEZ, as a “relative backwater.” China’s population has always been extremely unevenly distributed, and the coast has long been the economic heart of the country and where the vast majority of the population is concentrated. The Pearl River Delta, where Shenzhen is located, has historically been a trade entrepot for southern China that had sustained contact with other countries through emigrants, and via neighboring Hong Kong and Macau. Shenzhen’s economic success as a space of liberal experimentation in a country stifled by top-heavy and unrealistic policies is not easily replicable in areas with low populations.

In analyzing the winners and losers of experiments in governance, applying lessons learned from China’s experience with SEZs may not provide the economic rocket fuel startup cities advocates imagine in truly isolated “backwaters” with small populations, such as French Polynesia.

Can “Total Freedom” Be Achieved on Leased Land?

Various startup city advocates Lutter references generally seek to escape what they feel are the suffocating constraints of government. Ironically, seasteaders, formally the most ideologically pure libertarian advocates of startup cities, are now approaching governments around the world cap in hand and trying to negotiate the lease of land and SEZ status for their floating city scheme. They yearn for freedom yet align themselves with charter cities.

As conceptualized by Paul Romer, charter cities are not a rejection of government, but are intended as a way to encourage government reform to take place. According to Romer, charter cities should have “electoral accountability for the people who run the zone” and a government:

Any sensible reform zone will still have government, some type of government. It will be accountable in the way that governments around the world are accountable. We give government special powers, like the ability to put people in jail, but we also impose special mechanisms of accountability to make sure that those powers are not abused.

Far from being bastions of freedom on the high seas as conceptualized by Patri Friedman, startup societies are embarking on a journey of being free from the United States government, only to be embedded in the legal system and economy of a possibly corrupt or undemocratic host country with some degree of negotiated autonomy on leased land.

In essence they are trying to do in Honduras and French Polynesia what various Chinese players are already doing in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Oman, and more, yet without China’s political clout, financial strength, technical skills, or negotiating leverage. As such, China and startup cities advocates have similar instincts for sniffing out corrupt and institutionally weak host countries that are desperate for foreign investment. This is not a recipe for an equal or stable partnership.

Herein lies an important question: how “libertarian” or radical are the visions of American startup cities advocates when their ambitions align with projects like Forest City? How much can pure libertarian visions of “autonomous ocean communities” be compromised by working with corrupt and dysfunctional states to acquire leased land, until nothing remains except the impulse to dodge tax obligations and seek out pockets of deregulation?

Few regulations, tax-free zones, and varying levels of autonomy can readily be found in recent zones created by China, Saudi Arabia, and other wealthy and powerful states and corporations to support their geopolitical, economic, and social interests. In contrast, startup cities advocates are vying to be consultants and middlemen in the birthing of SEZs, seasteads, and other libertarian-inspired endeavors, while also seeking to permanently be in charge of running them. Lacking financing and land, they have very little skin in the game, little to offer, nothing to lose, and everything to gain.

In the crowded marketplace of schemes vying to attract investors, this is a tough sell.

Make Governments Compete—for Us

How can we make governments better?

That question drives much of what the Cato Institute does. The answers it generates, through policy papers, public presentations, op-eds, and the like, tend to have very broad reach. A Cato publication might call for a more efficient federal tax code, for instance, or for free trade among all nations. You could call this approach to government reform “a mile wide and an inch deep.”

Mark Lutter, author of the lead essay in this Cato Unbound and founder of the Center for Innovative Governance Research (CIGR), also evidently wants to make governments better. Like others in a new generation of reformers, however, he advocates trying radical reforms in small special jurisdictions. His essay trumpets that “hundreds of millions of people can be lifted out of poverty through a strategy of zone-based economic reforms,” and his CIGR calls for “new, semi-autonomous jurisdictions which can be used to rapidly improve governance in poorly governed areas … .” In contrast to the more typical approach, pursued by the Cato Institute and indeed almost every other think tank or policy group, Lutter seeks reforms that run, one might say, “an inch wide and a mile deep.”

Given that I used to work at the Cato Institute—as Director of Technology and Telecommunications back in the Clinton-Gingrich era—I am not about to criticize its general approach to government reform. It does well to focus on broad themes, given that its pro-liberty message has fans everywhere. When it comes to actually putting policies into practice, however, the approach followed by Lutter and other advocates of special jurisdictions might work better.

Changing the tax code for a whole country cannot help but rouse a swarm of objections. Changing the tax code for a single building, though? Easy. In fact, the United States has already turned that kind of reform into a standard operating procedure in its Foreign Trade Zones (FTZs). Hundreds of FTZs, scattered across the country, lie outside the reach federal customs, procedures, duties, or excise taxes, as well as non-federal ad valorem taxes on tangible personal property.

As documented in my just-published book, Your Next Government? From the Nation State to Stateless Nations (Cambridge University Press 2018), FTZs and other special jurisdictions have exploded in number, size, and diversity in recent decades. Though sometimes little more than over-planned boondoggles, convenient vehicles for corruption, or the vanity projects of megalomaniacal politicians, special jurisdictions, if done right, have the power to radically improve governments. How? Through competition.

From Little Jurisdictions, Big Reforms

Special jurisdictions offer governments a relatively easy way to try out reforms too risky to implement everywhere, all at once. China’s transformation from masochistic Maoist communism to hypocritical but comfortable capitalism owes much to this effect. First Hong Kong—itself a type of special jurisdiction—set an example for what free markets could do for the Chinese people. Next, the government of China allowed a few tentative reforms in nearby Shenzhen. After those experiments succeeded, the reforms spread. Today, perhaps ironically but at all events fortunately, more Chinese people live within so-called “special” zones than live outside of them.

Better government does not follow automatically simply from having lots of special jurisdictions, however. Those jurisdictions have to face incentives to improve. Economist Bryan Caplan recently put the problem this way:

Imagine a world with a thousand sovereign countries of equal size. This is far more decentralized than the status quo, right? Suppose further, however, that there is zero mobility between these countries. Labor can’t move; capital can’t move. In this scenario, each country seems perfectly able to pursue its policies free of competitive pressure. Why should we expect such policies to promote liberty, prosperity, or anything else?

The Chinese used special jurisdictions to find their way to better government not simply by having a lot of them, but by pitting them against each other in a race to encourage economic growth. Ronald Coase and Ning Wang describe the internal incentives for better local government in their excellent book, How China Became Capitalist (Palgrave Macmillan 2012).

Special jurisdictions alone do can little. If they do no more than create local privileges and fracture the rule of law, they might even do harm. If jurisdictions have to compete for free-flowing labor and capital, in contrast, they can help us discover new and better rules and institutions. According to Lotta Moberg’s pioneering book, The Political Economy of Special Economic Zones: Concentrating Economic Development (Routledge Studies in the Modern World Economy 2017), special economic zones (SEZs) promote the public interest best when they inspire broader adoption of locally successful reforms.

The best way to government reform? More competition among governments. And the best way to more competition? Special jurisdictions.

These observations encouraged the Startup Societies Foundation to create the Institute for Competitive Governance (ICG). As its Academic Director, I encourage research and development on how special jurisdictions can lead to more general reforms. ICG’s working theory: competition can offer a better way to better government.

Special Jurisdictions in Realpolitik

As Sarah Moser’s observes in her comments on Lutter’s piece, China, having turned itself into a nation of SEZs, has begun using them as a tool of foreign policy. Consider what happened in Sri Lanka. In 2008, it launched joint venture with China to build a deep-water port at Hambantota. After Sri Lanka defaulted on the loan for project, China relieved it of further liability—in exchange for a 99-year lease to use the port, which—surprise, surprise—could prove strategically valuable to a certain giant country’s growing navy. A similar scenario now looms in Kyaukpyu, Myanmar, where the Chinese government plans to finance and build a deep sea port and industrial zone.

China is not alone in using special jurisdictions to extend its reach. Thanks to its colonizing lawyers, England’s common law has won a foothold in both Dubai’s International Financial Centre and Abu Dhabi’s Global Market. Through such subtle but deep influences the City of London qua financial capital extends its reach and increases its revenue.

And where is the United States in this Great Game, special jurisdiction version? Remarkably, for a country that began, developed, and remains a collection of special jurisdictions: Nowhere. The United States does not lack for military presence abroad, of course. But parachuting in self-contained fortresses has a distinctly different effect than would building public infrastructure, investing in local commerce, and encouraging the rule of law. Though they arose by accident rather than design, perhaps the new SEZs arising in Afghanistan, on airfields left by departing U.S. military forces, offer a new model for winning influence abroad: less by building bases and more by building U.S.S. jurisdictions (for “United States Special,” of course).

Special Jurisdictions in the Real World

A closing point: Moser’s comment observes that some of the world’s most advanced special jurisdictions have arisen in, to put it nicely, some of the world’s not so advanced countries. Nobody should blame special jurisdictions for that, though. It turns out that the kinds of countries that summarily eject untitled residents from construction sites and hold the passports of immigrant laborers commit even worse atrocities as a matter of routine policy.

Just as sick people seek a doctor’s care, sick countries sometimes seek aid in special jurisdictions. Neither reformers nor their instruments have the luxury of working only with morally pure nation states (supposing such political unicorns to exist). Instead of faulting special jurisdictions for their inevitable association with troubled countries, Moser and others who hope for better should celebrate the potential of special jurisdictions to discover better ways to better government.

Paths to High Productivity

As a development economist, the biggest puzzle I face is “why don’t all countries in the world get to high A?”

I’ll explain what I mean.

Economists often characterize the total labor productivity of an economy (output per work hour) with an equation that describes output as a product of the “capitals” that are deployed (both physical capital like buildings, trucks, lathes, generators and human capital like knowledge, skills, abilities that people have) and then that function of capitals is multiplied by A, which is “total factor productivity” to express how effective/efficient those capitals are in producing output.

One easy way to think about the process of poorer countries getting more productive is that A represents codifiable technical knowledge—like how to build an internal combustion engine or how to design a factory to produce cotton textiles—and this technical knowledge is a “public good” that is non-rival and non-excludable. In this model A diffuses from high-A places to places that are initially low-A. This simple set-up produces an optimistic story: A (technical knowledge) converges across places, raises the productivity (and hence returns) to factors in poor places, and therefore people invest in factors (using domestic and foreign savings) and, over time, at a pace determined by the feasible pace of accumulating factors, poor countries become rich.

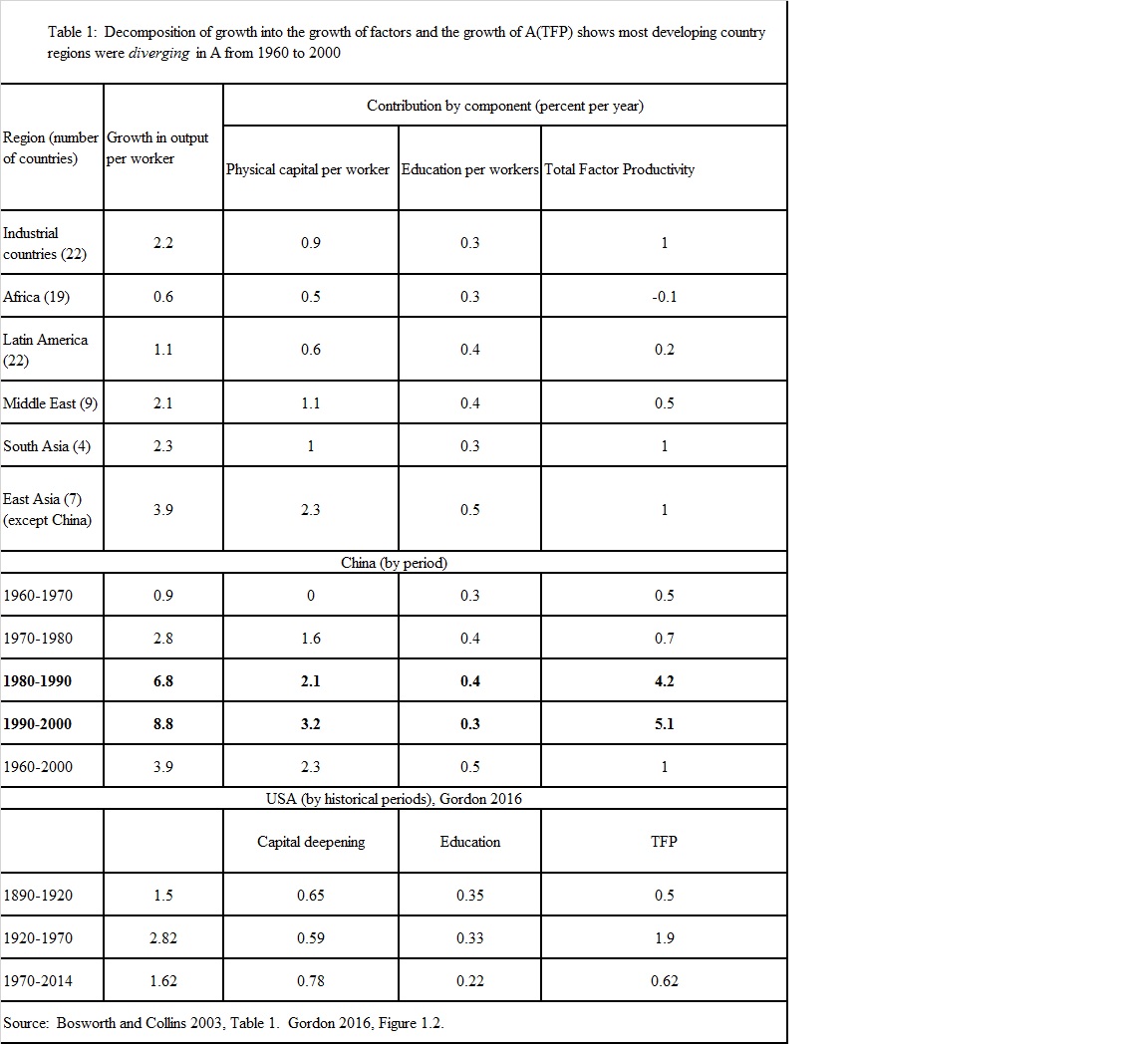

But by about the year 2000 it was clear this happy story of convergence mostly was not happening. Per capita incomes between rich countries and most poor countries did not converge (in the table below there was substantially higher growth in per capita incomes in developing regions than in the richer industrial countries only in East Asia and China). Moreover, what is really striking is that the lack of convergence is mostly not due to the inability of countries to mobilize savings and make investments in physical and human capital, but rather because A itself was diverging, or at least failing to converge. Table 1 is adopted from standard calculations of the decomposition of economic growth into factor accumulation and A (TFP) of Barry Bosworth and Susan Collins (2003, Table 1). None of the five regions (excluding China) had higher rates of TFP growth than the industrial countries. Moreover, Gordon (2016) claims USA TFP was 1.9 percent per annum in the fifty year period from 1920 to 1970 (in which it was already the leading economy) and none of the developing country regions achieved even half of that in the forty years 1960 to 2000. Comin and Mesteiri (2018) confirm that “intensity of use” of known technologies “accounts for the divergence during the twentieth century.

It is worth uncovering why this lack of convergence of A was so weird and why it set development economics off in completely different directions (and how that ended up with ideas like charter cities and special economic zones).

When development economics was becoming a field in the 1950s and 1960s it seemed obvious that (a) a large part of sustained economic growth since 1870 in the leading countries was “technical progress” in the sense of the expanded science and technology based knowledge embedded in new organizational practices and therefore (b) there were “advantages to backwardness” as it just had to be easier to adopt known ideas and practices than develop new ones from scratch, which Gordon (2016) argues is true. The rapid progress of Russia and Japan based on aggressively acquiring known technologies appeared to vindicate this view.

The acceptance of the finding that it was not primarily differences in factor accumulation that drove growth rates, and that A did not diffuse in ways that led to convergence, led to a series of papers and works that claimed “institutions rule.” Rodrik, Subramanian, and Trebbi (2004) actually used that title, but this was the rough implication of papers by many major economists around this period: Easterly and Levine (2002), Hall and Jones (1999), Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001), and of course Douglas North. The problematic nature of the “institutions rule” viewpoint was that none of these works tended to specify a model of the evolution of “institutions” and, as opposed to the optimism that A as knowledge would “naturally” diffuse across countries, there was a pretty decided pessimism that “institutions” were something that could and did remain the same over very long periods. It was easy to believe that since “institutions” were (or were sustained by) “norms” that there could exist low-level equilibrium traps—situations in which potential positive shocks or reform efforts would not be enough to escape the existing counter-productive norms.

I think this is the context in which the idea of charter cities came onto the development agenda as an intellectual last resort. If A diffused and growth was limited by available finance, work on finance. If the adoption of A was limited by “bad policies,” then work on getting rid of bad policies. If “institutions” constrained the improvement of A, then, if there was a feasible path to improved institutions, work on improving institutions. But what if none of that was true? What if the constraint to high productivity in a given space/territory was poor “institutions,” and what if these were caught in a persistent low level trap such that known and feasible improvement paths were not available? Then what one needs is a “big shock” to reset norms and create—at least in the limited space of a city, or province, or just a “special economic zone”—growth-promoting institutions.

But being a last resort just makes something potentially the least bad idea, and not a good idea. In the 1984 Ghostbusters movie they decide to cross the streams, in spite of the obvious risks of total protonic reversal, not because it was a good idea, but because it was a last resort, and all was lost to the Stay-Puff Marshmallow Man if they didn’t, so even a slim chance of success from crossing the beams was the best available option. Even if eliminating the last resort leads to full on pessimism, there are three good arguments why a “charter cities” or “spreading zones” approach is unlikely to work.

First, it requires credibility of a sovereign commitment to autonomy and to not interfere with the operation of the new “institutions” created by the charter city/zone. That credibility either comes because the existing sovereign government can make credible commitments or it can’t. If it can, then why are its “institutions” so messed up that it cannot fix them and needs an end-run? If it cannot, then it needs , as Romer argues, some other sovereign guarantor of the credibility of its commitment. But this requires that one sovereign (e.g. Honduras) cede sovereignty over a significant part of its existing territory to another sovereign (e.g. Canada). Now matter how instrumentally attractive this may be, and even in the best circumstances—unlike, say, ceding sovereignty to a Korean private company—the political optics of this are very bad.

Second, a key question is “how big/frequent/common is the political space in which the approach will work?” That is, across all configurations of the interests and “political settlements” of states, and across the capabilities the state can deploy, how frequent will it be that a state will have both the interest and the wherewithal to bring about a successful charter city (or other dynamic zone-like arrangement), but not have the interest and wherewithal to otherwise undertake less “last resort” successful reforms? After all, China both had the preceding successes in export oriented industrialization—Japan, Korea, Taiwan at a minimum—to learn from, and had the commitment, power, control, legitimacy, and capability to engage in deliberative experimentation to promote a new growth strategy. I suspect there are many states that are too weak to create a credible charter city in the first place (e.g. South Sudan) and many states in which the “deals”-based capitalism they are engaged in provides them with no political or economic incentives to do true arms-length charters. These stand in contrast to setting aside opportunities for insiders, as happened in Tunisia under Ben Ali, as well as many other states capable of pursuing rapid growth without the charter approach, like Indonesia under Soeharto, or Vietnam.

Third, my Harvard Kennedy School colleague Ricardo Hausmann has been doing very interesting work on why A has not diffused, and his “capabilities and complexity” approach suggests very different answers than the standard aggregate neo-classical production function. His model is that each product requires a recipe of inputs, and that more complex products are defined by needing not more of a standard aggregate input, like capital, but by many more inputs. His argument is that high productivity places are those that can bring together the longer and longer lists of capabilities needed for complex production. This therefore draws a distinction between the creation of special-purpose economic zones to facilitate the production of a very specific item (e.g. a zone for producing athletic shoes) and the creation of a large space, like a city, that can reap the economies of agglomeration. So a city can be a zone, but vice versa is unlikely. And this also reveals that the “seasteader” idea isn’t really a development agenda at all.

If China’s success since 1978 critically depends on the “zone” approach that was last successfully implemented 40 years ago, and that no one has replicated other than Dubai—which was essentially a real estate venture, not an approach to development—then these arguments get powerful support.

In sum, a charter city approach to developing growth-promoting institutions clearly can work, I would like it to work, but I think the reasoning that leads to such a quirky solution is more a reductio ad absurdum than a call to action.

The Conversation

Reply to Moser on Innovative Governance

It was a pleasure to read Sarah Moser’s thoughtful response to my essay. Though it was critical, I found myself agreeing with much of it.

Her essay as makes four important points. First, innovative governance projects already exist. Second, innovative governance has potential downsides. Third, the conditions responsible for China’s success are relatively unique. Finally, “total freedom” isn’t feasible, and governmental institutions are important.

Moser writes, “the new types of city building, governance, and urbanization of the ocean that startup societies describe are already underway.” Moser is correct in noting that innovative governance projects are underway worldwide, though they remain under-researched. Part of my goal with the Center for Innovative Governance Research is to jumpstart a wider conversation about innovative governance projects and capture new audiences.

I was first exposed to innovative governance via techno-libertarianism. However, over time I became frustrated with the lack of progress, as well as my realization that techno-libertarians were missing the wider context of innovative governance. This is not to suggest that they have nothing to offer to the conversation. Systematic thinking and willingness to experiment, two attributes commonly associated with techno-libertarians, are valuable additions to innovative governance.

Regarding the potential downside of innovative governance, Moser writes, “there is a wide range of negative impacts that deserve careful study.” I agree. While I believe the expected value of innovative governance is positive, we should not be blind to the risk involved. I share concerns about ecological damage, the property rights of indigenous or otherwise marginalized people, and the disappearance of welfare as governance becomes more of a service.

The proper tool to understand both the potential negative and positive impacts of innovative governance and to avoid falling prey to the nirvana fallacy is comparative institutional analysis. The alternative to innovative governance is rarely liberal democracy, but dictatorships, autocracies, or other forms of illiberal government. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, it costs on average 50% of a person’s yearly per capita income merely to legally register a business. Such unnecessary constraints on entrepreneurs are one reason Africa remains impoverished.

Moser’s third point focuses on China. She writes, “the success of Chinese SEZs cannot be celebrated in isolation from broader demographic factors and economic history.” I agree that innovative governance should not be thought of in isolation from larger demographic and geopolitical trends. While governance is important for the economic success of a city, it isn’t sufficient. One of the reasons I am most optimistic about innovative governance in Africa is the high urbanization rate which necessitates the construction of new cities.

Moser’s last point is that “total freedom” isn’t feasible. If by “total freedom” Moser means a Rothbardian property rights system, then I agree — territorial governance is not necessarily helpful. My interest in innovative governance is not to construct ideologically pure libertarian societies, but rather to build governments within the real world which improve human flourishing. I attribute much of the lack of success of libertarian innovative governance projects to their utopianism.

Charter cities, and innovative governance more broadly, are tools for governance reform, not for escaping government. One of the understudied benefits of innovative governance space is how charter cities can be used to improve state capacity.

Countries often remain stagnant because of regional states which are unable to control violence or provide basic public goods. Reforming these states internally could take decades by conservative estimates. However, charter cities can serve as catalysts to spark improvements in state capacity, bypassing existing government structures which might resist such improvements.

I appreciate Moser’s essay; it raises important challenges about the potential for failure in innovative governance projects that prioritize idealism over pragmatism. However, while she is pessimistic about the future of charter cities, I remain cautiously optimistic. We are in the early stages of a global revolution in governance. Given this, we should be aware of, and minimize, the downside risk. However, if managed correctly, innovative governance has the potential to improve hundreds of millions of lives on global scale. This is a future worth fighting for.

Why Charter Cities? A Reply to Tom W. Bell

In his response essay, Tom W. Bell lays out some of the reasons for favoring charter cities and other types of special jurisdictions as tools for reform (hereafter charter cities). The primary reason, he argues, is that competition between jurisdictions can lead to better outcomes. While competition is an important reason for favoring charter cities, it is one of several. The reasons for charter cities, in order of importance, are 1) the importation of good governance, 2) low cost experimentation in governance, and 3) jurisdictional competition.

There is rough consensus on what leads to economic development: rule of law, property rights, and an open business environment. As Hong Kong and Singapore demonstrated, a country (or city) with rule of law, property rights, and an open business environment can rapidly grow into a high-income country. The challenge is that many countries face political constraints which make them unable to implement rule of law, property rights, or an open business environment. In such circumstances charter cities are a political tool.

Charter cities are a political tool to overcome gridlock. By using narrow but deep reforms, particularly when they are applied to unpopulated areas, the public choice problems that often vex reforms elsewhere are minimized. Further, among for-profit charter cities, the logic of collective action is reversed. There is a clearly identifiable benefactor from such reforms, namely the developer, who is incentivized to lobby for reforms to increase their land values. This incentive alignment can help disrupt stagnant political systems which are captured by powerful interest groups.

The second justification for charter cities is experimentation. Importing good governance assumes that these particular reforms would ideally be implemented at the country level, but for political reasons they cannot be. However, there exists a different set of reforms as well, which are not clearly positive or negative, but are worth testing. Charter cities can be used for experiments to test the potential benefits of such reforms.

Glen Weyl and Eric Posner, for example, argued for a Harberger tax in their new book, Radical Markets (listen to my podcast with Glen Weyl here). Under a Harberger tax, people self-assess the value of their property. They pay taxes on their self-assessment, which incentivizes them to self-assess a lower value. However, if anyone desires to buy their property at the self-assessed value, they must sell it, incentivizing them to self-assess at a higher value.

It is unclear whether a Harberger tax will increase efficiency. However, it represents a powerful alternative to the current property rights system of freehold, which dominates most liberal democracies. Imposing a Harberger tax on a liberal democracy would be disruptive, causing social disorder. However, by implementing a Harberger tax in a charter city, it would be possible to test its effects with minimal disruption. If successful, the Harberger tax could be copied elsewhere.

The third reason for the importance of charter cities is competition. It is less important than the previously listed reasons because jurisdictional competition operates in fundamentally different ways from intra-firm competition.

First, it is a non-sequitur to argue that jurisdictional competition requires additional jurisdictions. Industrial organization means that different industries have different optimal firm sizes. The optimal firm size for jurisdictions could be larger than it currently is, given the economies of scale to national defense and internal markets. Alesina and Spoalore argue that states trade off the benefits from such economies of scale with the heterogeneity of preferences in larger jurisdictions.

Arguing that competition requires additional jurisdictions requires evidence that the current size of political units is inefficient. Given low international barriers to trade, as well as relative peace, this is an argument I am sympathetic to. However, it is not enough to simply assume that the need for increased competition implies the need for additional jurisdictions.

Second, it is not clear that the charter city “like” success stories result from jurisdictional competition. Hong Kong, for example, was a lucky accident resulting in British rule and in particular administrators, namely John Cowperthwaite. Singapore’s success was largely due to Lee Kuan Yew. Shenzhen resulted from the bottom up demand of Hong Kong businessmen looking for investment opportunities coupled with Deng Xiaoping’s ascent to power. Such examples fit within creative destruction in the broad sense, but hardly within intra-firm competition as it is typically understood.

Charter Cities Aren’t Necessarily Last Resorts

Lant Pritchett responds to my lead essay in part by reviewing the intellectual history that led to charter cities. Namely, there was a realization of the importance of institutions, combined with pessimism about institutional change and the existence of low-level institutional equilibria. Charter cities therefore “came onto the development agenda as an intellectual last resort.” They are a tool which can disrupt an existing low-level political equilibrium.

Pritchett then gives three reasons why charter cities are unlikely to succeed. First, the commitment problem. Charter cities require a credible commitment from a host country for the legal autonomy necessary to succeed, a commitment which they are unlikely to achieve. Second, there is the political space within which charter cities could be successful. Some countries, South Sudan for example, are too dysfunctional for charter cities. Third, a zone cannot be a city. High productivity places require a complex set of inputs making special purpose special economic zones unfit for generating sustained economic growth.

The commitment problem is the usual objection I hear from economists. The host country needs to both pass legislation which creates the legal autonomy necessary for a charter city, then credibly commit to respecting such legislation, otherwise no one would invest. This creates a conundrum as potential host countries which can credibly commit often do not need charter cities. Nevertheless, I think the commitment problem is overstated for several reasons.

First, the norms around sub-national legal autonomy are changing. For example, ten years ago the Seasteading Institute was founded to pursue legal autonomy in open waters, as it was assumed that no host country would be amenable to the level of legal autonomy they desire. They have since shifted their strategy, signing a memorandum of understanding with the government of French Polynesia. On a different note, Sri Lanka relinquished control of a port to China for debt relief. There are a handful of other examples which cannot be shared due to space and privacy constraints, but we are approaching an inflection point in governance, and governance forms which were previously unthinkable are now being thought.

Second, new city projects are proving that, at least for the real estate side, fear of future expropriation is not the binding constraint. There are dozens of multi-billion dollar new city projects around the world. Most such projects are privately led or are public-private partnerships. The entrepreneurs I speak with also don’t put such a high emphasis on the commitment problem, suggesting that economists overstate its importance.

Third, there are a number of ways to tie the hands of the host country regarding the legal autonomy of the charter city. First, successful institutional change requires the allegiance of the ruling elite. For a charter city, this means ensuring that the ruling elite has an economic interest in the success of the charter city, either by having them build factories there, own land, or otherwise invest in the project. Second, the International Court for the Settlement of Investor Disputes can be used by charter cities to reclaim wrongly appropriated property. Third, it is possible, as Romer suggested, to use international treaties to bind a country. Either a guarantor country could administer the charter city, or a country investing with their sovereign wealth fund could demand a treaty, or an IGO could use their treaty to protect the legal autonomy of the charter city.

Pritchett’s second objection involves the potential political space for charter cities. I agree that charter cities aren’t applicable in all circumstances. Some countries, Rwanda for example, which is already growing rapidly, would see little benefit from a charter city. Other countries, the Democratic Republic of Congo for example, are too violent to implement a charter city. Nevertheless, there is a large political space within which charter cities could have a meaningful impact.

Latin America, for example, has long been stuck in the middle-income trap. Charter cities could help them escape from it. Africa has many countries which could benefit from charter cities, including Kenya, Nigeria, and Zambia. Further, it is important to note that for charter cities to be successful they don’t need to have “good” institutions. They only need to have “better” institutions than the alternative. A charter city in Honduras, for example, would be a success if they could implement Mexican or Salvadoran institutions, much less American institutions: El Salvador’s per capita income is 50% greater than that of Honduras.

I am not sure I fully understand Pritchett’s third objection. He writes, “high productivity places are those that can bring together the longer and longer lists of capabilities needed for complex production. This therefore draws a distinction between the creation of special-purpose economic zones to facilitate the production of a very specific item (e.g. a zone for producing athletic shoes) and the creation of a large space, like a city, that can reap the economies of agglomeration.” I agree; this is why I choose to focus on charter cities, rather than special economic zones.

Special economic zones typically create level effects, increasing efficiency on certain margins. They rarely create growth effects. To benefit from economies of agglomeration, there needs to be a sufficiently large population with a diverse economy. That is best developed in a city.

However, I would push back on Pritchett’s emphasis on high productivity places. Charter cities do not have to be high productivity per se, they only need to be higher productivity than the alternative. I believe the best model for most countries interested in charter cities is not Dubai, but Shenzhen, which slowly worked its way up the value chain, beginning with highly labor-intensive manufacturing.

Pritchett concludes by pointing out that Dubai, the most successful “charter city” since Shenzhen, is a real estate development. That is an important point. The charter cities of the future are not purely political projects, but also real estate projects. Real estate creates a sponge by which the benefits of improved governance can be captured, incentivizing developers to improve governance. Charter cities are both political and business projects.

I do not think that Pritchett is right that charter cities are an “intellectual last resort” to avoid the pessimism implied by institutional analysis. Sarah Moser’s essay demonstrates that charter city like projects are being built across the world. However, assuming Pritchett is right, he would be wise to remember that the Ghostbusters saved the world by crossing the streams.