About this Issue

The U.S. healthcare sector is unique in the world. But this is not to say that it’s a model.

American healthcare is paid for by a complicated mix of patient payments, private insurance, and various federal programs. It features an unusual employer-based insurance system owing to a longstanding tax loophole. Provision varies significantly from one state to another because of federalism.

Why not just simplify the whole thing? It’s a reasonable question, because the system is well-known to bear a great deal of waste, fraud, and abuse. An individual consumer’s health care costs bear little relation to scarcity and may deviate wildly from what other consumers are paying. Many have no health insurance at all and can’t afford what it would cost.

One proposed simplification is to expand the federal government’s Medicare program—originally focused on seniors—to cover everyone. Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has promoted the idea, and it remains popular among progressives. Is it a good idea?

The Cato Institute’s Director of Health Policy Studies Michael F. Cannon writes this month’s lead essay, in which he casts doubt on Medicare for All in a variety of ways. In the coming days, we will post response essays by Prof. Sherry Glied of New York University, Prof. Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University, and Dr. Micah Johnson of Harvard Medical School, each of which will offer a different take on the question. We look forward to readers’ comments as well.

Lead Essay

M4A Would Deliver Authoritarian, Unaffordable, Low-Quality Care

The far left has made “Medicare for All” its rallying cry. Medicare is the 55-year-old federal program that provides health insurance—if that’s the right term—to 58 million elderly and disabled U.S. residents. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has introduced, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) has endorsed, legislation that would expand Medicare by enrolling all 319 million or so lawful permanent U.S. residents, subsidizing more health services (e.g., long-term care), and making all covered services “free” by eliminating all patient cost-sharing.

Attempting to describe the scope, costs, and political implausibility of Medicare for All tests the limits of human language. If Medicare for All has any merit, it is that so many of its costs are foreseeable that it will never become law. At least, not all at once. The true danger of Medicare for All is that it is acting as a stalking horse for piecemeal proposals that would end up in the same place but hide the costs until it is too late.

We will begin by deconstructing the ideological narrative—what Medicare for All supporters consider facts—upon which support for the idea rests.

Every Other Nation Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?

The cornerstone of this ideological narrative is the idea that Medicare for All is feasible because every other advanced nation has already enacted it or something similar. Sanders’s web site proposes “joining every other major country on Earth and guaranteeing health care to all people as a right, not a privilege, through a Medicare-for-all, single-payer program.” In fact, not a single advanced nation has ever implemented what Medicare for All supporters propose.

Under Medicare for All, a single entity—the U.S. government—would administer a health care program that would centrally plan a $4 trillion health sector for a diverse population of 319 million souls. No advanced nation—not Canada, the United Kingdom, or even Sanders’s beloved Scandinavian countries—have a health system that compares to the scale, scope, and centralized decisionmaking of Medicare for All.

Medicare for All would control access to health care for far more people than any advanced nation’s system. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service covers a population one-fifth as large as the United States, with nearly eight times the population density. Canada’s system covers a population smaller than the state of California. Texas and California are each larger than the combined populations of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden.

A Medicare for All program would control far more resources than any other nation’s health system. In terms of dollars, the U.S. health sector is three times as large as China’s, 10 times the size of India’s, and larger than the health sectors of the next 22 OECD countries combined.

It would centralize control over the health sector more than any advanced nation. Under Medicare for All, the national government would dictate a uniform set of benefits and dictate prices for all covered medical, dental, and long-term care services. Canada’s health system leaves many of those decisions to provincial governments, which make varying decisions based on local needs. Canada’s health system is less centralized than even the U.S. Medicaid program. The British and Scandinavian systems likewise delegate much decisionmaking to local authorities.

No advanced nation has a health system that is as closed as Medicare for All. Sanders’s bill would create a true single-payer system first by guaranteeing coverage of everything under the sun—and then outlawing private insurance that covers anything the government covers: “it shall be unlawful for a private health insurer to sell health insurance coverage that duplicates the benefits provided under this Act.” If a right to health care means anything, it means consumers must be free to pool their resources to obtain better health care. Medicare for All explicitly prohibits that right.

Advanced nations don’t treat their citizens that way. Just in case the government-run health systems in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom aren’t perfect, those governments leave consumers free to purchase private insurance. Millions of Danes, Finns, Norwegians, and Swedes seeking “greater choice of private providers” and “to avoid waiting lists for elective treatment” purchase supplemental coverage from private, for-profit insurance companies.

Not even Canada goes as far as Medicare for All in limiting the freedom to pool medical expenses. While Canada prohibits private insurance for services the government covers, its health system does not cover items that Medicare for All would. Canadians are therefore free to purchase, and a majority do purchase, coverage for such services as outpatient prescription drugs and dental care from (for-profit) private insurers. Even Canadians have more health freedom than Americans would under Medicare for All.

Iceland is an example of an advanced country with almost no private health insurance. But Iceland’s health system differs from Medicare for All in other important ways. It has cost-sharing for primary and outpatient care, and generally doesn’t cover dental care. More important, health spending in Iceland is 0.05 percent of U.S. health spending and its population is smaller than that of the 56th largest U.S. city (Honolulu). Iceland’s health system is at best a Medicare pilot program, and those tend not to scale. (More about why below.)

Medicare for All would be a titanic, unprecedented, and uncontrolled experiment with the health of every American.

It Would Cost Less, If You Ignore History

A related foundational precept of this ideology is that Medicare for All would cause U.S. health spending to fall in line with the rest of the world.

This precept also has a patina of plausibility. Other advanced nations issue a government guarantee of access to care for all citizens, and even when we control for population and size of the economy, they all spend far less than the United States. Compared to the average for OECD countries, the United States spends nearly twice as much of its GDP (16.9 percent vs. 8.8 percent) and 2.7 times as much per capita ($10,586 vs. $3,994). Medicare prices, moreover, are lower than private-sector prices. Private insurers pay hospitals two to four times what Medicare pays for the same services. Since Sanders’s bill would pay providers current Medicare prices—including for patients who now fetch those higher private-payer prices—spending must go down. Even former Republican Medicare trustee Charles Blahous agreed in a study he did for the Koch-funded Mercatus Center. Q.E.D.

The first problem with this argument is the unstated premise that government is good at setting prices.

Though health care providers tend not to make a stink when it happens, Medicare is as likely to set prices too high as too low. Need an example? When progressives complain Medicare Parts B and D should reduce the prices paid for prescription drugs, they are admitting tacitly what libertarians acknowledge explicitly: the government is overpaying. Want another? Gundersen Health System in Wisconsin found its input cost for total knee replacements, including the surgeon and anesthesiologist, was “at most” $10,550. The average Medicare payment for that procedure (DRG-470) exceeded that amount in every state, reaching as high as 215 percent of it in Maryland and 238 percent in Alaska.

Markets also get the prices wrong—all the time. The difference is that while competitive markets constantly push prices toward marginal cost, government pricing errors do not self-correct. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) complains about this problem all the time. In 2018, the commissioners wrote of their “long-standing concern” that Medicare overpays procedure-based specialists and radiologists relative to primary care physicians. The decades-long fight over whether the government should “negotiate with drug companies”—as if it isn’t already negotiating, and losing—is another case in point.

Medicare for All supporters respond by pointing to the gap between Medicare prices and frequently higher private-sector prices, as if that spread somehow makes government look good. On the contrary, government itself widens that spread by doing lots of things to drive private-sector health care prices higher. Not least, the federal tax code encourages excessive insurance and discourages price-consciousness among the 178 million Americans with employer-sponsored insurance. Prices for hormones and oral contraceptives, for example, soared at the precise moment the federal government mandated 100 percent coverage of hormonal contraceptives. Even Medicare and Medicaid push private prices higher through various mechanisms. Medicare for All supporters are therefore lauding government and condemning markets for a problem that government largely creates.

A second problem is the mind-blowing assumption that Congress can hand health care providers the sort of pay cut Sanders’s bill envisions.

The Sanders bill proposes to pay all providers the same prices Medicare currently pays, which are more than 40 percent less than the prices they receive for privately insured patients. Warren assumes Medicare for All would increase health care consumption more than 20 percent yet leave total health care spending no higher than under current law. In other words, she assumes providers would deliver 20 percent more output—drugs, doctor’s visits, and hospitalizations—for zero additional pay. Blahous implies that—if Sanders’s bill were to pass Congress with those price cuts intact—U.S. health spending would fall. Whether Medicare for All would reduce health care spending is thus a question of how likely it is that such price reductions would pass Congress.

How likely is it? It’s not impossible, just highly improbable.

Members of Congress are hesitant in the extreme to do anything that cuts either government or private payments to doctors and other health care providers back home. My colleagues Charlie Silver and David Hyman wrote a book—Overcharged—that chronicles how the health care industry games Medicare and other government programs to keep excessive prices and payments coming their way. In November, they chronicled more than half a dozen ways the industry has worked all three branches of government in recent years to keep excessive Medicare payments flowing. As I write, I am marveling at a banner ad from an industry-backed conservative group that, in the name of fighting socialism, aims to prop up the excessive prices Medicare pays to drug companies.

It is difficult to overstate how incapable Congress is of limiting health spending at all, much less to the extent Medicare for All supporters are promising. The New York Times reports the debate over surprise medical bills offers “a miniature version” of a debate over Medicare for All. There, opposition from a small share of physicians who would see their incomes fall just 20 percent was enough to scuttle legislation that would have saved consumers money by curtailing surprise medical bills. Reporter Margot Sanger-Katz summarizes:

Even when you have bipartisan support, bicameral support, support from the White House, support from really important and influential consumer groups, and the health insurance industry spending millions itself to advocate for this policy, and employer groups spending money trying to advocate for the policy[, and] the public polling being so overwhelmingly in favor of this, and the fact that this is not really harming all doctors or all hospitals, it really is harming a subset of doctors, a subset of hospitals, many of whom are doing something shady and unscrupulous—[it] still couldn’t happen.

A representative of the left-leaning group Families USA lamented that “not getting surprise bills done does not bode well” for Medicare for All’s ability to restrain spending.

The Affordable Care Act reinforces the point. The only way it was able to overcome provider opposition to its reductions in the rate of growth of future Medicare spending was to offset every $1 in forgone payment increases with $2 in new subsidies to providers. Even then, many of the limits on provider incomes did not survive. The Obama administration gutted a quality-improvement program in a way that also gutted the ACA’s lower payments to private insurers participating in Medicare (more on that below). The Cadillac tax, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, and other provisions died bipartisan deaths in Congress. The lesson of the ACA is that government has to spend $2 just to save $1, and even then it often doesn’t work.

It is no mystery why Congress keeps Medicare spending excessively high and cannot enact the sort of cuts Medicare for All supporters keep promising. The benefits of excessive Medicare spending fall on highly organized interest groups: health care providers (who spend money on lobbying and contributing to political campaigns) and seniors (who vote). Though these groups constitute a minority of the population, they spend and vote on health issues far more than the rest of us. So Congress caters to them, whether or not it’s good for the nation as a whole.

This dynamic is so intractable, even some who advocate single-payer in general oppose enacting it here. The late Princeton University health economist Uwe Reinhardt helped the Taiwanese government implement a single-payer system. Yet he had a very particular reason for counseling against adopting single-payer in the United States:

I have not advocated the single-payer model here because our government is too corrupt. Medicare is a large insurance company whose board of directors accepts payments from vendors to the company. In the private market, that would get you into trouble.

U.S. health care spending is excessive because of Medicare, not in spite of it.

A “Right”—to Expensive, Dangerously Low-Quality Care

The final fairy tale we will examine here is the notion that expanding Medicare to the entire population would guarantee access to care by making health care “a right, not a privilege.” On the contrary, Medicare for All would trample health care rights. The only right it would guarantee is a right to dangerously low-quality medicine.

President Barack Obama may have been both incorrect and insincere when he endlessly pledged that “if you like your health plan, you can keep your health plan” under the Affordable Care Act. Nevertheless, the reason he made that false promise is that he and other Americans intuitively sense that the most important health care right is the right to make one’s own health care decisions. As Obama put it in an address to Congress, the ACA “would preserve the right of Americans who have insurance to keep their doctor and their plan” (emphasis added).

As noted above, Medicare for All would leave Americans with even less freedom to buy private insurance than Canadians—and Canada’s Supreme Court held that country’s ban on private insurance to be a human rights violation.

Indeed, prohibiting private insurance would be—to coin a phrase—a Medicare for All-sized violation of Americans’ health care rights, quickly throwing nearly 200 million Americans out of their private health insurance plans. The employer-sponsored plans that cover 178 million Americans? Gone. The individual-market plans that cover 14 million Americans? Gone. (The 20 million, or one third, of Medicare enrollees and the 54 million, or two thirds, of Medicaid enrollees in “private” plans don’t exactly have a right to have the government subsidize private insurers on their behalf. Still, those plans? Gone. Good luck selling that to 56 percent of Minnesota seniors.)

Taxes also infringe on the right to make one’s health care decisions. Blahous estimates that even if Congress doubled all federal individual and corporate income taxes, it would not be enough to pay for Medicare for All. The Council of Economic Advisors estimates the necessary tax increase would leave the economy 9 percent smaller than otherwise. (The Great Recession erased just 4.3 percent of GDP.) The CEA projects “free” health care would leave households with $17,000 less to spend on non-health items. Free health care sounds great. But if the taxman leaves you penniless, you’re not really the one calling the shots.

After repealing your health care rights, Medicare for All would replace them with dangerously low-quality health care. Part of the problem is rationing by waiting, a problem that plagues health systems in United Kingdom, Canada, and elsewhere. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the Sanders bill would create “a shortage of providers, longer wait times, and changes in the quality of care.” But there’s a larger problem inherent in any single-payer system, whether it exhibits waiting lists or not.

Health care is so complex that every method of paying health care providers creates perverse incentives. Promoting all dimensions of quality requires open competition among multiple payers with different payment and delivery systems. A single-payer system, no matter what form it takes, cements in place one set of perverse incentives and eliminates the competitive pressures that would otherwise rescue patients from the low-quality care that results.

Take Medicare, which is the largest purchaser of health care services in the United States and likely the world. Medicare has spent five decades rewarding low-quality care and punishing high-quality care. Former Medicare administrator Tom Scully complained, “Everyone with an M.D. or D.O. degree gets the same rate [from Medicare], whether they are the best or worst doc in town. Every hospital gets the same payment for a hip replacement, regardless of quality.”

It’s worse than that. MedPAC warns that Medicare traditionally has not rewarded doctors and hospitals who reduce medical errors, hospital acquired infections, medication errors, or unnecessary re-admissions, and often it punishes them instead: “Medicare often pays more when a serious illness or injury occurs or recurs while patients are under the system’s care.” Medicare thus has a “neutral or negative” impact on the quality of care. And we wonder why preventable medical errors are the third-leading cause of death in the United States.

Primary care is relatively simple, right? In 2018, MedPAC wrote, “The Commission has also become concerned [Medicare’s physician] fee schedule—with its orientation toward discrete services that have a definite beginning and end—is not well designed to support primary care, which requires ongoing care coordination for a panel of patients.” Note the recency of “become.” Medicare for All would turn the entire health system over to central planners who took 50 years to notice they were rewarding low-quality care, and who still haven’t fixed that glitch.

Pilot programs to improve quality or reduce spending in Medicare usually flop, and those that succeed don’t scale. Decades after markets developed health systems that maximize incentives to reduce hospital acquired infections, Medicare is still only taking baby steps in that direction. In one Medicare quality-improvement program, one fifth of the hospitals that received bonuses had below-median quality scores. When the ACA combined cuts to Medicare-participating private insurers with bonuses for those that provided high-quality coverage, Medicare rescinded the cuts and sabotaged the quality incentives by offering the bonuses meant for high-quality plans to mediocre plans, too. On and on it goes.

Some argue Medicare for All would better prepare the United States to fight pandemics like the current coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19) outbreak. Yet many British doctors argue the NHS is unprepared, and cite tens of thousands of unfilled clinician positions. Medicare has spent 55 years discouraging efforts to contain infections by shifting the financial cost of preventable infections from health care providers to taxpayers. Medicare pays ambulatory surgical centers regardless of whether they give their clinicians flu vaccines; as of next year, it won’t even measure whether they do. Health systems like Kaiser Permanente internalize those costs and thus tend to do a better job of vaccinating both their enrollees and clinicians. Medicare for All would eliminate that superior model, subsidize the model that discourages efforts to fight contagion, and—at least under the Sanders bill—it would result in less health care capacity, including fewer hospital beds.

Conclusion

What is it about a president who doesn’t understand how viral immunity works and a vice president who is coy about whether he thinks organisms mutate and evolve that makes Medicare for All supporters think letting the government control the entire health system would better prepare us for pandemics?

People who understand the current Medicare program have a difficult enough time defending it, let alone arguing we should expand it. When Medicare supporters talk about Medicare becoming an “active purchaser,” they are tacitly acknowledging that after 55 years, Medicare is still rewarding high-cost and dangerously low-quality care. When they complain about fragmentation and talk about the need for medical teams and coordinated care, they are complaining about Medicare. When they complain about unnecessary re-admissions, or the lack of electronic medical records and comparative-effectiveness research, they are complaining about Medicare. They promise that reform is on the way. And they are right: reform is always on the way. It never arrives.

That’s why even many Democrats oppose the idea. Rep. Donna Shalala (D-FL), who ran the Medicare program as Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Clinton, says, “No one I have met who supports Medicare for All understands the Medicare program.” A left-leaning scholar of international health systems was more blunt when he bellowed into my ear, “Bernie knows absolutely nothing about health care!”

Response Essays

M4A Has Its Flaws, but Let’s Not Whitewash the Status Quo

Michael Cannon wrote his post about M4A an eon ago, when Senator Bernie Sanders still had a decent chance of winning the Democratic presidential nomination and COVID-19 was causing lockdowns only in distant China. I write today, barely a week later, in self-isolation in New York City and–with Vice President Biden, who does not favor M4A, well ahead in the Democratic primaries. Biden’s success means that whatever happens in November, we are now unlikely to move directly to M4A; as I discuss below, the COVID-19 experience is one more push away from the status quo ante. What can we learn about the debate over M4A that will inform the next steps we will need to take? Michael’s post offers a starting point for this learning.

Michael makes several sound points in his post. First, other nations do not operate M4A systems–most allow some private insurance, most incorporate some cost-sharing, most are much less highly centralized than M4A. Second, governments do not do well at setting prices in general, and our government is particularly bad at it. Third, other countries use forms of rationing different from ours, such as waiting lists, and regulatory price setting schemes here and elsewhere do not provide adequate incentives for high quality. These points are valid–and they do point away from M4A–but to an even greater extent, they also point away from the U.S. status quo. M4A has its problems–but the existing US health care system has even more. The current crisis will shine a harsh light on some of those problems.

To date, the weaknesses of the U.S. response to COVID-19 have had little to do with the fragmented, relatively private nature of the health care system. Other countries with universal systems are also struggling with what is, largely, a public health response. But that will change in the next few weeks as people continue to become ill and need care.

Absent intervention–and such intervention is very likely -the U.S. health care system will produce two outcomes that would never occur in our counterpart countries. First, families who become very ill and hold private insurance will face very substantial medical bills, especially if they need services delivered by hospitals or providers outside their insurance networks. As Michael points out, other countries do incorporate cost-sharing in their health plans–but in other countries, cost-sharing is modest and often linked to income. Here, the median out-of-pocket maximum payment for in-network covered services in single coverage plans is above $4,000. The effects of high cost-sharing will likely be exacerbated in the case of an infectious disease, since there’s a chance that multiple family members will become ill at the same time. It’s no surprise that President Trump and other politicians are already trying (so far unsuccessfully) to mitigate this financial impact. Rationing care for critical illnesses through high cost-sharing raises distributional questions that even relatively conservative governments find troubling. For illnesses where patients have little control over the course of treatment, rationing care in this way also doesn’t make sense from an economic perspective. The effect of high cost-sharing on patients’ financial well-being with COVID-19 is visible and immediate–but it is not fundamentally different from the effect of that same cost-sharing on the financial well-being of patients with other serious and costly illnesses. With or without M4A, we will need to move away from this approach.

An even greater ethical–and political–challenge will face our system if, as many observers expect, the supply of ventilators and other essential equipment is inadequate to the need generated by COVID-19. The current logic of the U.S. health care system suggests that a hospital, particularly a for-profit hospital, ought to prioritize access to costly services, such as ventilators, to privately insured patients who pay the most for services, even if an uninsured patient, or a Medicaid patient, would gain more health benefit from that service. Heightened media attention to COVID-19 makes the scenario of rationing access to life-saving ventilators by price somewhat unlikely in this case–but uninsured Americans routinely face limited access to life-saving therapies that are in short supply. That doesn’t happen elsewhere.

As Michael notes, private insurance in other countries does enable purchasers to get faster access, more choices, and greater amenities than those who rely exclusively on public insurance. But in other countries, this improved private insurance access is limited to discretionary procedures, choices among similarly credentialed practitioners, and non-essential amenities. Other countries may not have single-tiered insurance, but they do have universal and rather egalitarian coverage for critical care. That is likely to be an even more widely held perspective in the United States after this crisis.

Michael’s second point is that the U.S. government is likely to do a poor job of cost containment. Private insurers do pay much more than Medicare does for most hospital and physician services, but Michael is right–not for everything. Until recently, Medicare paid more than private insurance for lab tests and medical equipment. Medicare payments are on a par with private prices paid for primary care doctors and mental health professionals. What’s special about these cases? They are all situations where there is a large set of relatively similar suppliers and entry is relatively easy, so that there are multiple competitors; and where the quality of a good or service is readily apparent to the purchaser. Moving forward, we should build a health system that enables the use of market forces in these situations, perhaps through a supplemental private insurance mechanism.

Unfortunately, for structural reasons, those two critical conditions are rarely present in the health care system–and they certainly don’t obtain for ICU care and other critical services needed now. Most health care markets are simply too small to support robust competition, and health care services like these are too complex to be easily evaluated by purchasers.

In circumstances where those conditions don’t currently hold, do private prices make more sense than Medicare prices? The argument for relying on the market to set prices is that private actors will be more responsive to new information than governments can be, and that they will incorporate that information into prices. We can test that proposition by looking at the services for which these prices diverge. It turns out there aren’t many–private insurers mostly just follow Medicare relative pricing patterns–that is, the relationship between the price of a complex service and a simple service is just about identical among private insurers, as in Medicare. Deviations occur most often when providers have more bargaining power and can negotiate for higher payments and more attractive terms. Michael is right–governments are often lousy at establishing appropriate prices–but in the absence of robust competition and observable quality, they seem to do at least as well as the private sector.

Michael ends his piece with the claim that the quality of health care is meaningfully better in the United States than elsewhere. There are studies that find better quality for specific conditions at specific times, but the overwhelming preponderance of evidence finds that health care quality, at least measured in terms of outcomes, is generally worse in the United States than in most other high-income countries. In part, that is because average quality includes both those with good coverage and those with limited access. But recent research finds that health outcomes even among the richest Americans are no better than among their counterparts in Norway, which spends far less on care, while outcomes for lower-income Americans significantly lag those of their Norwegian counterparts. The COVID-19 epidemic will provide another data point. I hope that American hospitals, which spend about twice as much per hospital day as the OECD average, will obtain better outcomes in the treatment of patients with severe disease–but nothing I’ve read or seen suggests that they will.

M4A is not, in my view, the best direction forward for the United States. Like Michael, I think that the very high degree of centralization implied by that plan is both anomalous in an international context and problematic for budgetary and political economy reasons. But that’s no pitch for the status quo. It’s much worse than Michael suggests–and much worse than M4A as well.

The Economic Case against Medicare for All

Everyone should have health insurance coverage and access to health care. Is Bernie Sanders’s Medicare for All proposal the best way for the United States to achieve that? In his lead essay on the topic, Michael Cannon answers an emphatic no. His answer emphasizes three major themes. First, he argues that no country as vast as the United States limits the availability of private insurance, centrally controls health prices and provision, and provides health insurance coverage to its entire population. Second, he argues that it’s farfetched to expect large savings from replacing private insurance and Medicaid with federally managed public insurance given the government’s long track record of failure at managing Medicare. Finally, he argues that formally acknowledging health care as a right would limit access, worsen quality, and strip away Americans’ rights to seek their own care or coverage outside the monopolist Medicare for All system.

The first two points that Cannon raises are simple matters of fact. The scale of the U.S. system swamps other countries’ systems. Of course, Sanders’s supporters point to the scale as a feature, not a bug, with large potential for savings through lower administrative costs and paying less to providers. And scope itself is not destiny. After all, even small Vermont’s single-payer experiment failed to launch under the weight of its costs.

We agree with Cannon’s second point: across the history of Medicare, the U.S. government has never been able to implement and stick with value-enhancing reforms when they threaten special-interest groups. To adapt the Chicago Cubs’ unofficial motto, “anyone can have a bad half century.” This is a record to run from, not to run on.

Cannon’s third point is a grim prophecy. Imposing one-size-fits-all coverage, shifting all pricing decisions and costs to the federal government, and prohibiting any outside option will harm Americans’ finances and freedoms with nothing to show for it in terms of health.

About those cost savings. With the federal government fully financing our health care system, politicians have incentive to shift away from on-the-books budgetary costs to off-the-books but very real expenses. Headlining these costs is at least an additional $600 billion per year needed to finance the budgeted $2 trillion per year due to the economic drag caused by the excess burden of taxation. There are also palpable costs to individuals. Rather than paying through patient cost sharing, which is banned under Sanders’s plan, people would pay in the form of fewer services and lower intensity of treatment per encounter. These costs are direct consequences of the proposed slashes in providers’ payments and the need for draconian supply rationing to limit overuse in the absence of patient cost sharing. As documented in Japan and Canada, these policies result in more delays, more visits to resolve health problems, and lower productivity.

Medicare’s payment rules already substantially shape how health care is delivered in the United States. For example, in 2009 Medicare cut payments to independent cardiologists for some common tests but left untouched their payment for cardiologists employed by hospitals. Subsequently, for some imaging services Medicare paid hospitals nearly twice as much as they paid independent physicians for the same service. The effects were predictable. The percent of cardiologists employed by hospitals rocketed up; people received much more cardiac imaging from hospital outpatient departments and less from freestanding physician offices. In a system without any other source of insurance, traditional Medicare’s current designation as the 800-pound gorilla in the U.S. health care system would be replaced with a 5,000-pound elephant seal.

While proponents view the heft of Medicare for All as an asset, it amplifies the effects and risks of three insurmountable problems that Cannon raises. First, there is no single best way to pay healthcare providers. Each system, whether fee-for-service, prospective payment, capitation, or salary for physicians, creates distortions between what is financially best for providers and what is best for us as patients. Any payment method must cover providers’ fixed costs for them to remain open, but any method that pays above marginal costs will give providers incentive to overtreat. Any method that pays below marginal costs, such as capitation, gives them reason to withhold treatment. In our current system, providers offered government prices below their marginal costs can refuse to participate in the program, or they can eat the losses if their margins from private payers are large enough to keep them afloat. Under Medicare for All, providers would have no other patients or payers to turn to, forcing them to exit the market altogether.

In the current U.S. system, non-Medicare insurers rely on a range of blended Goldilocks solutions. In fact, the popular private insurers known as Medicare Advantage plans are set apart from traditional Medicare precisely by their flexibility to set payment methods and levels and their ability to exclude certain providers. This has allowed Medicare Advantage plans to drive up value, improving coverage and outcomes beyond traditional Medicare. And people have responded. Over one third of Americans age 65+ have opted out of traditional Medicare and into these private plans, including those with chronic conditions such as diabetes, schizophrenia, and lupus, for whom tailored Special Needs Plans are available. Similar dynamics play out in private markets, Medicaid, and many systems around the world. Under Sanders’s proposal, those plans are illegal. There would be no customization of coverage, no ability to exclude providers, and no possibility for us to vote with our feet and seek care and coverage from models that bring us more value.

A second problem is how to set the right relative price levels for various health care providers, technologies, and services. Cannon notes that many observers believe that Medicare currently overpays specialist physicians and underpays primary care physicians. Medicare already attempted to resolve this problem with its shift to the payment system known as RBRVS nearly three decades ago. What happened? The government abdicated ownership of the coding system and price setting decisions to the American Medical Association. The group tasked with setting relative prices for each service was controlled by the specialists’ organizations, who tipped the scales in their favor. RBRVS, despite its stated objectives, became a system by which the rich got richer.

Under a market system, the prices negotiated with providers result from supply and demand. These prices act as powerful signals to providers about which markets to enter, which services to provide, how many hours to work, whether specialty training programs are worth the extra years, and which potential technologies risk capital and time researching and developing. Market prices also steer buyers, for example by reducing demand where prices are high due to limited supply. While these mechanisms are imperfect, they embed safety valves and self-correction. They not only protect and benefit those in the private market but also serve as guardrails for Medicare’s price-setting decisions. Under Sanders’s proposed system, these guardrails of supply and demand are stripped away and replaced by unilateral decisions made by the government monopsonist. As Cannon makes clear, our history has shown that these governing agencies systematically favor special interests. And no matter how brilliant and benevolent their technocrats, they will not have access to the wisdom embedded in market signals.

A third problem Cannon raises is the erosion of individual liberties. With the entire U.S. health care system financed through the federal government, the government has a controlling interest in any of our choices that might affect our health care spending. Even under our current system, the externalities of health care costs are used as a rationale for various government interventions, such as motorcycle helmet laws and the Affordable Care Act’s experiments to “bend the cost curve.” Rightly or wrongly, the current pandemic’s health care utilization externalities have been used by governments across the United States to justify making it illegal to work or to leave our homes in many circumstances, even to surf in the ocean. Applying C. S. Lewis’s insights, the government’s power of the purse under Medicare for All gives justification for a system of “omnipotent moral busybodies… who torment us for our own good … without end…. To be ‘cured’ against one’s will and cured of states which we may not regard as disease is to be put on a level of … domestic animals.”

Suppose that we were willing to swallow the economic losses of Sanders’s policy, cede control to special interests and technocrats, give government greater reason to intervene on our individual decisions ,and eliminate all alternatives if it would lead to better and more equal health outcomes. Would the proposed Medicare for All plan achieve this? Experience says no. As countries expand their governments’ involvement in health care, they do not benefit from longer life expectancy on average, nor do they achieve any greater equality in life expectancy within the country.

For all of the amplified risks and problems, there’s little upside from this version of universal coverage. In the ongoing conversations about health care reform, we hear concerns about high and growing out-of-pocket costs and concerns about people slipping through the gaps in our system and facing reclassification risk due to pre-existing conditions. We share these concerns and the values underlying them. It is precisely these values, combined with our perspectives as economists and analysts of health care systems, that motivate our objections to Medicare for All.

Health Care Under Medicare for All Would Be Universal, Affordable, and Secure

On the day Michael Cannon published his essay attacking Medicare for All, the Centers for Disease Control released new numbers showing that America had 374,000 cases of Covid-19. In the three weeks leading up to publication of the essay, 17 million Americans lost their jobs and filed for unemployment benefits. Because we link health coverage with employment, the coronavirus is starting to unravel our health insurance system. The high price of American health care has also become a threat to public health, pushing people away from medical care even as a deadly contagion courses through our communities.

The pandemic displays the adversity of human life with the tape sped up. Rarely are so many lives upended so quickly, but economic disruption and medical illness are not anomalous events. They’re inevitable. Covid-19 has exposed and inflamed the problems in our health care system, but its troubles are chronic.

Medicare for All proposes a different path forward. The debate over M4A hinges largely on the ethical and economic wisdom of treating health care as a social good rather than a market product. Into this debate, Cannon puts forth an economic view that I find fundamentally mistaken: that Medicare is hopelessly expensive, and private markets are more effective at controlling health care costs.

Markets have many attractions, but for most health care services the evidence is quite clear that market forces are simply failing to keep prices under control. This should not be terribly surprising. There are many well-known reasons that health care does not function like a normal market good, and health care markets fail in predictable ways. We pay dearly for these failures—usually with our bank accounts, but too often with our health.

Compared to private insurance, Medicare has a much better track record for keeping care affordable, making it a sensible foundation for expanding health coverage across the population. And despite Cannon’s arguments to the contrary, M4A would be far more similar to the universal health care systems around the world than our current system is, and it would give all Americans access to quality health care.

The High Price of Our Medical Marketplace

Let’s start with the economic facts. The United States spends twice as much per person on health care as our peer countries, as Cannon describes. But we don’t use more health care: we actually have fewer doctors and hospital beds than our peers abroad, and in turn Americans have fewer doctors’ visits and hospital stays. We spend so much because we are charged the highest prices in the world whenever we do get care—and also because we spend the most money in the world administering our complex and fragmented payment system. The world’s most expensive health care system does not buy us better health: we live shorter, sicker lives than our peers abroad.

Cannon offers a simple diagnosis: “U.S. health care spending is excessive because of Medicare.” But the facts are incontrovertible: prices in the private insurance market are much, much higher than prices in Medicare. For physician services, private-sector prices are 35 percent higher than Medicare prices on average, and higher still for specialty care. Hospital prices in private insurance are double the prices in Medicare. In outpatient medical centers owned by hospitals, prices in private insurance are triple the prices in Medicare. It’s no surprise that when Americans turn 65 and switch from private insurance to Medicare, their spending drops precipitously.

Cannon’s argument that Medicare pays too much for knee replacements unintentionally proves the point: the Congressional Budget Office studied that exact procedure (DRG-470) and found that private insurers pay twice as much as Medicare does for total knee replacements, more than $27,000 compared to $13,500.

There’s no mystery why Medicare pays lower prices than private insurance companies. Medicare has the power and leverage to decide unilaterally how much it will pay for different kinds of medical care. In contrast, every private insurance plan needs to negotiate its own rates against powerful hospitals and doctors’ groups. Hospitals and doctors leverage this system—and all the market failures that undergird it—to charge privately insured patients the highest prices on the planet.

The United States also spent over $800 billion on health care administration in 2017—nearly a quarter of national health expenditures. The private insurance market drives up these administrative costs. To see why, consider the fact that each year the Cleveland Clinic must negotiate the prices for 70,000 billing codes across 3,000 different private insurance plans—that’s 210 million prices. Hospitals then need to hire an army of billers and coders to translate everything that happens on its premises into one of these prices. Private insurance companies also spend more than 13% of premiums on overhead and profit, compared to just 2.3% in traditional Medicare. All told, the United States spends three times as much administering our insurance system compared to our peer countries.

Cannon seems to recognize that our private insurance system is far more expensive than Medicare but argues that the government “widens that spread [between Medicare and private prices] by doing lots of things to drive private-sector health care prices higher.” The most telling argument he provides for this claim is that the tax break for workplace health coverage “encourages excessive insurance and discourages price-consciousness”.

To be sure, our employer-based health insurance system is a national liability as tens of millions of Americans lose their jobs during the coronavirus recession. But workplace coverage isn’t “excessive.” It’s inadequate.

Here’s the reality of employer-based health coverage. Two in five visits to the emergency department come with a surprise bill that’s not covered by insurance. Same for hospital admissions. The average deductible before insurance kicks in is $1,655 for an individual, and certain family plans have an average deductible approaching $5,000. (Recall that four in ten Americans have less than $400 in readily accessible savings). The kicker? Researchers have discovered that high deductibles do not lead to “price shopping”—they just slash health care use across the board. (They also cause 9-month delays in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer.) Even with all these inadequacies, workplace insurance premiums have increased by more than 50% over the last decade, now exceeding $20,000 per family every year.

In short, the problem isn’t government encouraging “excessive” private insurance. The problem is that selling health care as a market product is extraordinarily costly: our expensive private insurance system has failed to prevent runaway price increases, and Americans are left paying more and getting less. M4A offers an opportunity to bring health care prices back to earth, giving Americans more for their money.

Health Care Around the World

Cannon also criticizes the notion that M4A is similar to other countries’ health systems, arguing that “not a single advanced nation has ever implemented what Medicare for All supporters propose.”

Universal health care systems can be designed in numerous ways, and it’s true that M4A does not copy any other country’s system wholesale. But the key features of M4A all have international precedent.

Let’s run through the examples that Cannon gives for how current M4A proposals differ from other countries’ health systems. Canada’s single-payer program does not cover prescription drugs. M4A would—and so do Denmark, England, Australia, France, Norway, and Sweden. Iceland requires a small co-pay to see a primary care doctor. M4A would not—just like Canada, England, and Denmark. England allows private insurance to cover the same benefits as the public plan. M4A would limit private insurance to services the public plan does not cover—similar to Canada and Medicare today. Canada’s system is largely administered by the provinces. M4A would include a large federal role—and so do France and Taiwan.

Of course, the policy questions raised by M4A ultimately should be debated on their merits, not based on how closely they match the details of any particular international system. Should there be co-pays and deductibles, and if so for what kinds of care? Should private insurance be permitted to cover the same services as the public plan? Should states have a larger role? Each country has answered these questions differently, and the M4A bills in the House and Senate provide their own set of answers. Even as we debate these important policy questions, it’s clear that any version of M4A would be much closer to the international norm than our current system.

The Right to Health Care

Finally, Cannon says it’s a “fairy tale” to think M4A would make health care a right.

Let’s start by examining what it means to make health care a right. A person with a right to health care is entitled to receive health care based on medical need, rather than ability to pay, social class, education level, place of residence, work history, or other factors. A society that protects the right to health care must define a comprehensive set of health care services that its members are entitled to.

Cannon makes several arguments against the idea that M4A would make health care a right. First he asserts that the “only right” guaranteed by either Medicare today or M4A is “a right to dangerously low-quality medicine.” But this charge is unconvincing. Americans on Medicare rate the quality of their care higher than older adults on private insurance. Seniors on Medicare also have similar or better access to care compared with people on private insurance based on measures like waiting times and ability to find a specialist. Compared to countries with universal health care systems, Americans die more often from conditions that adequate medical care can ameliorate. In short, quality health care is wholly compatible with making health care a right.

A different argument put forth by Cannon is that M4A wouldn’t make health care a right at all. On the contrary, “Medicare for All would trample health care rights.” He explains by giving his own definition of the right to health care: “If a right to health care means anything, it means consumers must be free to pool their resources to obtain better health care.” If Cannon views this as a sufficient condition for securing the right to health care, the implication is the following: A person has a right to health care if they are entitled to receive only the medical care they can afford on the private market, including through the purchase of private health insurance.

This market-based view of rights is clearly problematic. It implies that merely putting health care up for sale constitutes making it a right. It implies that an uninsured woman who cannot afford cancer treatment has a right to health care, but a woman on Medicare with guaranteed access to cancer treatment does not have a right to health care. Clearly, this gets things exactly backwards.

Put simply: The right to health care entitles a person to receive medical care based on medical need, not based on income. Health care is not a right in today’s America. It could become one under M4A.

The Future of Health Reform

American society is in the midst of a generation-defining upheaval. The pandemic is exposing the terrible human and economic costs of an overpriced health insurance system that crumbles at the very moment it’s needed most. The coronavirus is a product of nature, but it’s a human choice to let medical illness destroy the finances of entire families, or to quicken the spread of a contagion by letting high prices keep people away from care.

The time will come when we need to rebuild our economy and our health care system. When looking toward this future, Medicare for All offers a serious vision for how to make health care universal, affordable, and secure.

The Conversation

America’s Costly, Ineffective Status Quo

Jay Bhattacharya and Jonathan Ketcham have seconded Michael’s post opposing a single payer plan for the United States. Unfortunately, they’ve done it by defending the performance of the U.S. private system relative to systems in other countries and by defending the performance of the private sector of the U.S. health care system in setting prices—arguments that have no validity at all.

With respect to the relative virtues of U.S. health care, they rely on remarkably dated reports to assert that other countries’ systems (lumped together as government-run, despite the myriad differences among them) are more expensive than they look or have worse outcomes. The Danzon study is from 1992; the Peltzman study is identified mainly from variation in the 1950s and 1960s.

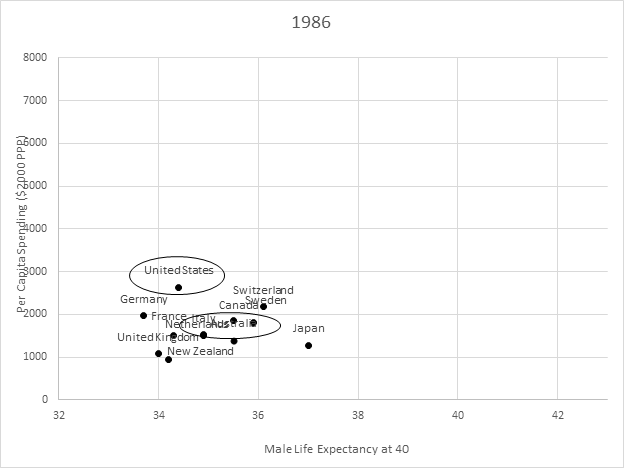

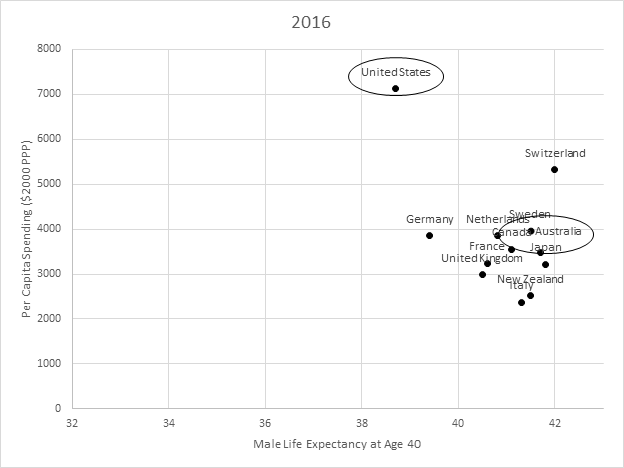

The truly terrible overall performance of the U.S. system, in terms of both outcomes and costs, is evident in the two charts below, which use standard data from the OECD health database on purchasing power parity and inflation-adjusted spending and male life expectancy at age 40. The first one is from 1986 (the period examined in the Danzon study and the far end of variation in the Peltzman study).

We don’t stand out much relative to lots of other countries in that 1986 chart, so it’s at least arguable that we aren’t doing particularly badly. But look at the next chart, from 2016! Compare us to, say, Australia—a country that operates a public-option style health care system (or choose a different country if you’d prefer). Between 1986 and 2016, all these other countries saw vastly bigger improvements in life expectancy at 40 (beyond the age at which the effects of violence, fast cars, and a wild life are likely to manifest) than we did at vastly lower cost. And our relative results would be even worse if we looked at younger adults or women instead of middle-aged men (and no, it’s not obesity or even opioids—the deterioration in U.S. performance predates the opioid epidemic, and Australia is second only to us in the OECD in terms of obesity rates). Given the extraordinary difference in purchasing power–adjusted spending relative to these other countries, we ought to expect far better performance from the U.S. health care system than elsewhere—instead, our outcomes are far worse.

And it’s not just a distributional problem. Look at the recent analyses of life expectancy in Norway. Even the richest Americans do not do any better than the richest Norwegians—despite the fact that our health care system costs, on average, 70% more than their system does. It goes almost without saying that poor Norwegians do a lot better than do poor Americans.[1] Single payer may not be the right way to go—but not because systems with more government controls do worse than ours.

And what about the argument about government price setting and the absurdities of Medicare cardiologist pricing? Those claims, too, would be more convincing if there were much evidence of private plans doing price setting much better. But Medicare Advantage plans nearly always pay at traditional Medicare rates[2]—if they did not, all their clever payment arrangements and utilization review would not leave them competitive with traditional Medicare. In the commercial market, private insurers don’t have the leverage to pay at Medicare rates—but they use the same relative rate schedule as Medicare almost all the time[3]. In markets with little competition (and there are a lot of those), private payers do even worse. They not only pay high rates, but use payment systems that provide worse incentives than Medicare.[4] They also followed the same Medicare payment practices around cardiologists, although they were under no regulatory obligation to do so[5].

So I stand my ground. Single payer may not be the best health care system out there—but neither is the one we’ve got.

Notes

[1] Cutler, D. M. (2019). Life and Death in Norway and the United States.Jama,321(19), 1877-1879.

[2] https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52819, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/workingpaper/53441-workingpaper.pdf

[3] Clemens, Jeffrey, and Joshua D. Gottlieb. “In the shadow of a giant: Medicare’s influence on private physician payments.”Journal of Political Economy125.1 (2017): 1-39.

[4] Cooper, Z., Craig, S. V., Gaynor, M., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). The price ain’t right? Hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured.The Quarterly Journal of Economics,134(1), 51-107.

[5] https://www.denverpost.com/2013/05/13/facility-fees-inflate-hospital-prices-for-common-services/