About this Issue

Abundant natural resources may seem a national blessing, but in many countries around the world, they turn our to be a curse. Studies abound showing that developing countries sitting on massive oil or mineral reserves are less likely to be democratic, less likely to respect the basic rights of citizens, more likely to be ruled by predatory political elites, and more likely to torn by brutal civil war. Is this just a deep, and deeply depressing, feature of the world we live in? Or can wealthier countries (which make up the market for most of these resources) and international institutions somehow intervene to alleviate or even lift the resource curse?

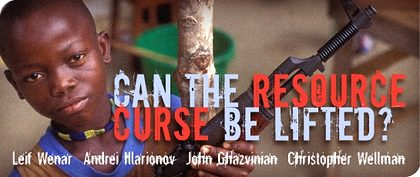

In this month’s Cato Unbound political philosopher Leif Wenar presents a provocative proposal for deploying an international property rights framework in which natural resources under control of the world’s most illiberal regimes are treated as stolen goods. Commenting on Wenar’s lead essay, we have Cato senior fellow Andrei Illarionov, the former chief economic advisor to Vladimir Putin; journalist and historian John Ghazvinian, author of Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil; andWashington University political philosopher Christopher Wellman, an expert in matters of international justice.

Lead Essay

We All Own Stolen Goods — and How Defending Property Rights Can Help the World’s Most Oppressed People

You very likely own stolen goods. The gas in your car, the circuits in your cell phone, the diamond in your ring, the chemicals in your lipstick or shaving cream — even the plastic in your computer may be the product of theft. Americans buy huge quantities of goods every day that are literally stolen from some of the world’s poorest people. These thefts are permitted — indeed encouraged — by an archaic rule of international trade that violates the most fundamental rule of capitalism: to protect property rights.

Tracing these stolen goods back to where the thefts occur lands us in some of the most wretched places on earth. What these countries have in common is an abundance of natural resources and plentiful political violence and corruption. All suffer from what Joseph Stiglitz and Jeffrey Sachs call “the resource curse.” Here dictators and insurgents sell off the country’s resources to foreigners, terrifying the people into submission while keeping the wealth for themselves.

The lavishly tyrannical Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea has become richer than Queen Elizabeth II by selling off the country’s oil and gas while killing or menacing anyone who might try to stop him. Obiang is the kind of dictator who has not shied from having himself proclaimed “the country’s God” on state-controlled radio, or from having his guards slice the ears of political prisoners and smear their bodies with grease to attract stinging ants. Obiang sells two-thirds of Equatorial Guinea’s oil to American corporations like ExxonMobil and Hess, and has recently spent 55 million of these petro-dollars to add a sixth private jet to his fleet. His playboy son and heir (who earns $5,000 a year as a government minister) prefers Lamborghinis, and recently spent $35 million on a house in Malibu. Meanwhile raw sewage runs through the streets of the country’s capital, three quarters of the country’s people suffer from malnutrition, and most citizens are forced to exist each day on what you can buy in America with one dollar. Obiang does not need to worry about the health or education of the population: he gets the money he needs to maintain his despotic rule by allowing foreign corporations to set up offshore platforms to extract the country’s oil.

Resource-cursed countries like Equatorial Guinea are prone not only to authoritarian rulers but also to civil strife, since the prospect of obtaining fabulous wealth by wrenching resources from a poor country often sets off a violent struggle for the prize. In 2004 a cabal of businessmen (including Margaret Thatcher’s son Mark) financed mercenaries who attempted to overthrow Obiang and replace him with a puppet president who would funnel the country’s oil revenues to the plot’s financiers. (The coup failed and Obiang had the captured leaders tortured.) Nor is Equatorial Guinea the only country whose resources have cursed it with authoritarianism and civil war:

- In the late 1980′s and early 1990′s Pol Pot supported the Khmer Rouge army by capturing and then plundering a strip of Cambodian territory rich in rubies and timber.

- In Sierra Leone in the 1990′s insurgents recruited child soldiers to scare much of the population away from the country’s rich diamond deposits with a brutal campaign of shootings and machete amputations. The rebels enslaved many of the remaining locals to work in the pits, selling these “Blood Diamonds” to international merchants like De Beers who then set them in wedding rings that Americans now wear as symbols of enduring love.

- The highly repressive Burmese military junta remains in power today partly by selling $2.8 billion of natural gas to Thailand each year and using these revenues to buy advanced weapons from India to quell domestic dissent. The regime is being protected from UN sanctions by China partly in exchange for access to large offshore gas deposits.

- In the Democratic Republic of Congo right now more than a thousand people die every day in the chaos caused by militiamen fighting over the minerals used to make our cell phones and laptops, who rape village women with bayonets and clubs as a tactic of war.

Authoritarianism and civil war both impoverish the people of resource-cursed countries. Sierra Leone this year ranks 177th out of 177 countries on the Human Development Index. Social scientists say that resource exports are correlated with higher rates of child malnutrition, lower healthcare and education budgets, higher illiteracy rates, higher poverty rates, and lower life expectancy.

The natural resources that the strongmen and civil warriors sell off are made into products sold in America. The money we spend on these products goes back to pay for their Kalashnikovs, helicopter gunships, and fleets of private jets. Paul Collier estimates that 290 million of the world’s “bottom billion” people are caught in what he calls “the resource trap.” Millions of these poor people must watch helplessly as their countries’ resources are sent overseas while our money flows in to the men with guns.

This is literally theft. The authoritarians and insurgents have no right to sell these countries’ resources. As the ancient Roman legal maxim says, Nemo dat quod non habet: no one can give what they do not have. The authoritarians and insurgents do not own these countries’ resources. The natural resources of a country belong, after all, to its people.

George W. Bush and Tony Blair recently and repeatedly invoked this principle of national ownership in the case of Iraq: “The oil belongs to the Iraqi people,” Bush said, “It’s their asset.” Nor is this principle parochial to any particular ideology: Hugo Chavez and Ayatollah Khamenei have proclaimed the principle as well. All of these leaders are drawing on one of the deepest ideas in modern international law. This is the principle of national ownership declared in Article 1 of the primary human rights treaties, ratified by the United States and the vast majority of the countries of the world: “All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources.”

The principle of national ownership is deeply embedded in international law, but it is also violated daily under cover of a rule from the days of European colonial empires. By this archaic rule the internationally recognized power to sell off the territory’s resources is vested in anyone violent enough to cow a country’s people into submission. By this rule any tyrant or civil warrior can gain the right to sell off a country’s resources simply through force of arms. According to this archaic rule for selling resources, might makes right.

It is this archaic “might makes right” rule that generates systematic incentives toward the curses of tyranny, violence, and poverty. Authoritarians who gain the resource right use the money from resource sales to buy weapons and spies to keep the population living in fear. Coup plotters look for ways to grab the resource right from the current regime and then become authoritarians in their turn. Rebels who can seize control of resource-rich territory gain the funds they need to start or escalate a civil war. And the people, whose resources are being sold off, become not the beneficiaries of this wealth but the victim of those who use their own wealth to repress them. “Might makes right” is the rule that sets off a violent contest to extract poor countries’ resources while crushing popular resistance, and it is the rule sends the products of crime into our gas stations and shopping malls.

How bad is the problem of stolen resources? The U.S. government uses the seven-point Freedom House scales to rate each nation on how much control citizens have over the those who hold power in their country. The very worst countries — the “sevens” — are places like Burma, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan and Zimbabwe. Taking these very worst countries as the places where the people could not possibly be authorizing the dictators and civil warriors to sell off their country’s resources, we can measure the amounts of stolen resources that enter America each year. By these official U.S. criteria over 600 million barrels of oil — more than one barrel in eight — have been taken illegitimately from their countries of origin. Stolen oil may be in your car’s gas tank right now. Stolen oil might have been used to make the computer mouse in your hand.

What can be done? One option is a public pressure campaign to divest from companies that invest in resource-cursed countries, as is endorsed by Nicholas Kristof in the case of Sudan ( “Is your pension fund helping finance the Janjaweed militias that throw babies into bonfires in Darfur?”). Another possibility, in countries where this is politically conceivable, would be to institutionalize Vernon Smith’s proposal for a “People’s Fund”: a mutual fund built up by auctioning the country’s natural resources, from which any citizen could at any time withdraw their per-capita share of the revenues.

The most promising strategy, however, is to enforce property rights directly: to take legal action in U.S. jurisdictions against the middlemen who trade Americans’ dollars to the worst regimes in exchange for stolen resources. This means taking corporations like ExxonMobil and Hess to court for receiving stolen goods. The international and American laws needed are already in force: these legal cases could be brought tomorrow. International capitalism has already created strong laws and institutions for enforcing these property rights.

Americans may or may not blame these corporations for trading their dollars for stolen resources. These corporations are merely doing what they are designed to do, taking the “might makes right” rule as part of accepted business practices. Yet neither these corporations nor market-friendly governments can resist the reality that a significant portion of international commerce today is trade in stolen goods. More than any other country, the United States has worked to create a modern international order that protects human rights, especially the human rights that are property rights. This is why legal cases requiring the United States to follow its own principles are waiting to be made.

However, upholding market principles is not as simple as bringing some court cases. Stopping American corporations from transporting stolen oil from a country like Sudan will not end the resource curse there. We know this because the U.S. government has barred American energy companies from trading with the regime in Khartoum since 1997, in part because of this regime’s grim record on human rights. Yet the genocidal Sudanese regime continues to sell the country’s oil to China, using the money to buy more Chinese arms to menace the populations in Darfur and the south.

This is disastrous for the Sudanese, and it is also a problem for Americans. Stolen Sudanese oil today percolates through the Chinese economy, becoming part of the Chinese imports that Americans buy every day. Americans right now can’t help dirtying their hands with stolen Sudanese oil when they shop at Target and Best Buy.

Discouraging China from buying cursed Sudanese oil is possible, and again turns on enforcing property rights — this time through trade policy. The key insight is that when China exports products made using the looted Sudanese oil it is not engaging in trade. It is literally passing stolen goods.

Say that China buys $3 billion worth of oil from the regime in Khartoum. The correct response on a property rights approach is for the United States government immediately to announce a Clean Hands Trust for the People of Sudan. This trust is a bank account that the U.S. government will fill until it contains $3 billion. The money to fill the trust will be raised from tariffs on Chinese imports as they enter the United States. The money in this Clean Hands Trust is to be held for the people of Sudan until a minimally decent, unified government is in place. At that point the $3 billion will be turned over to the true owners of the stolen oil: the Sudanese people.

The Clean Hands Trust will protect the American people from becoming tainted with the oil that China gets illegally from the regime in Khartoum. The tariffs extract from Chinese imports the value of the oil taken from Sudan, and the trust holds this money in reserve until it can be given back to the Sudanese people.

With the tariffs in place American consumers can buy Chinese goods with clean hands. The Chinese, for their part, will have much less of an incentive to buy more oil from Sudan — knowing that if they buy $2 billion more oil then the United States will impose tariffs worth $2 billion more on their goods. The Sudanese people will know that there is a great deal of money waiting to be turned over to them if they can replace the regime that is looting their resources with a minimally decent, unified government. The trust gives the Sudanese people an extra incentive to unite in installing a government that is in some way responsive to the people’s wishes, while drying up the revenues that support and arm the current regime in Khartoum.

The trust-and-tariff mechanism protects property rights by retaining the value of the stolen property for the owners of that property: the citizens of Sudan. The tariffs here are different from other tariffs: they are “anti-theft tariffs” designed to enforce property rights. The trust-and-tariff mechanism is no more a restraint on free trade than a court order to return stolen property, and no more a restraint on free trade than a prison term for a thief. China, having violated market rules by passing stolen goods, has no standing to complain when these violations are rectified.

The World Trade Organization, for example, could not allow China to impose trade restrictions in retaliation for these anti-theft tariffs. The Chinese could no more protest these anti-theft tariffs in the WTO than they could protest sanctions were they to occupy Sudan militarily and attempt to sell off its oil. The WTO should find these tariffs as acceptable as the 1990 UN sanctions that kept Iraq from selling stolen oil from Kuwait.

This trust-and-tariff mechanism will generate strong incentives for a variety of American economic interests to support the property-based approach. The instant that China contracts for the Sudanese oil, American manufacturers will lobby the U.S. government to set up a Clean Hands Trust. Many American companies (in apparel, electronics, machinery) will want these tariffs to protect them against Chinese competition in their sector. The American banking industry will also be enthusiastic about the Clean Hands Trust, as American banks will hold the tariff proceeds in trust until these are returned to the Sudanese. Both the manufacturing and banking sectors will also welcome the opportunity publicly to support measures aimed at helping the victims of a genocidal regime.

This trade policy will also be popular across the American political spectrum. Supporters of the free market will support it for correcting a major flaw in the global economy by enforcing property rights. Protectionists will support it for protecting good American jobs against Chinese competition. Security advocates will support it for strengthening failed states where terrorism can incubate. Environmentalists will support it for at least temporarily raising oil costs and so lowering carbon emissions. And humanitarians will support it for improving the prospects of millions of the most oppressed people on earth.

Americans today can’t help funding death and terror when they buy gasoline and magazines, jewelry and laptops, cosmetics and cell phones. The materials used to make these goods are not just stolen: they have been stolen from the world’s poorest people using weapons paid for with money gained from previous sales of stolen goods.

Peoples have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights). Trafficking in a country’s valuable natural resources without the people’s consent certainly crosses that line. The priority in reforming global trade must be to lock in the rights that define the market order. The first step in improving the prospects of poor people is to enforce the rights they already have.

—

Leif Wenar is this year a visiting professor at Princeton. From September 2008 he will hold the Chair in Ethics in the School of Law at King’s College London.

Response Essays

The Wenar Proposal vs. Realpolitik

Reading Leif Wenar’s excellent and impassioned article, I am reminded, yet again, of how critical it is for policy makers to come to grips with the thorny question of the “resource curse” — both in Africa and elsewhere. In the time I spent in 2005 and 2006 researching and reporting my book on the African oil boom, I was repeatedly struck by just how unfair it seemed for tyrants such as Obiang to keep adding to their private jet fleets while their people were dying of easily preventable diseases. I came into this story from the perspective of a journalist, rather than a policy expert, concerned with sharing an important story with the world rather than tackling the difficult business of actually coming up with solutions. That is why I will always have huge respect for people who come up with innovative proposals, such as the one we have before us today. Leif Wenar’s contribution is certainly one of the freshest and most original I have read in the past several years. The resource curse riddle, I am convinced, has both structural and behavioral components to it, and any meaningful solution will have to address both facets. Dr. Wenar’s certainly does that.

I must confess that I am a little troubled, at the outset, by some of the more philosophical questions of sovereignty and representative government that such a fundamental rethink of property rights throws up. Even if we accept the idea of property rights as a universal value (an admirable position, to be sure), it seems to me that there is a dangerous precedent to be set if we invest it with a quality of extraterritoriality that risks turning every country’s citizens into hapless victims of their own government’s “theft.” It is not hard to imagine the kinds of cases that would be brought against the United States, for example.

But I am certainly prepared to set aside such global moral quandaries for the time being. What I am more concerned with at the moment are some of the practicalities of how such a system would work. To this end, I wonder if I could just raise a few points for clarification.

My first question is this: Who determines when the government of Sudan, say, has reached the standard of a “minimally decent, unified government”? Will this be a congressional committee of some sort? Desk officers at the State Department? Or some independent board that has yet to be set up? How will we protect against the influence of lobbyists? Given the manifest financial windfall that goes along with being removed from the doghouse, isn’t there a risk that this process will become deeply politicized? Or simply reduced to who has the best PR apparatus?

Next there is the question of what happens once this benchmark has actually been met. The words “minimally decent” suggest that the bar is being set fairly low. This is a reasonable and eminently defensible position, to be sure. After all, no one would suggest that Sudan must be turned into some sort of Sahelian version of Norway before it can get its Clean Hands Trust funds released. So what counts as “minimally decent and unified” in this context? We can probably all agree that Equatorial Guinea does not make the cut as things stand. But would we apply the term to, say, Gabon? Is it all Obiang has to do to get his hands back on the oil money just to act a bit more like Omar Bongo? That wouldn’t be hard, really. Set up a couple of weak opposition parties, tell your goons not to get quite so carried away in the prisons, and you can keep all your mansions and your private jets. Isn’t there a risk here that we’re offering the carrot of (what amounts to) a 100% bonus royalty payment, financed by American consumers, to governments that may actually be rather corrupt?

But there is something more worrying in this benchmark, and it is to do with the word “unified.” Certainly, we all want strong, unified states in Africa where people aren’t butchering one another over access to resource wealth. Unfortunately, though, setting this as (in effect) a criterion for funding would only have the opposite effect.

Let us not forget how the rebellion in Darfur actually began. In 2003, sensing that for their decades of warfare the Sudan People’s Liberation Army in the south of Sudan were about to be rewarded with a massive, internationally brokered power-sharing arrangement, certain groups in Darfur began attacking government installations, hoping to achieve a similar settlement. Setting up a process in which governments cannot access “their” money until they have unified their countries, it seems to me, gives any aggrieved minority the power of an instant veto-risking destabilization in what are often already unstable countries. It strikes me that African governments already have enough built-in incentives to promote unity and stability within their own borders and that punitive measures only serve to ratchet up the stakes (in a way that is ironically similar to the effect that resource windfalls have on these countries in the first place). It strikes me that the Sudanese people do not need “an extra incentive to unite in installing a government that is in some way responsive to the people’s wishes.” What they need are peacekeepers.

My main concern with this proposal, though, has to do with the effect it might have on the international trade environment. This is probably not the place to debate free trade (and certainly, I claim no expertise to do so). But it seems a given that (to take the example at hand) China would instantaneously retaliate by imposing tariffs of its own against American products, and could easily justify them by claiming that the United States has bought “stolen goods” from the people of Iraq, or Taiwan, or even Equatorial Guinea (where the biggest business partner remains the United States, not China).

At its heart, this proposal is based on an assumption that lawmakers will embrace a mechanism that uses tariffs to achieve political ends, and that they will be happy to put noble ideas ahead of the free-trade agenda. As such, it seems unlikely to pass. Dr. Wenar makes the case that these are “anti-theft tariffs” and therefore “different from other tariffs,” but this seems a point likely to be lost (or at least dismissed as semantic) in the realpolitik of policymaking.

He is right that American manufacturers would be tripping over themselves to support such an initiative, but herein lies the rub. Lobbyists for American industries already have huge influence over Congress, and yet have not been able to revoke China’s Most Favored Nation status. It seems unlikely that some three-steps-removed idea of property rights accruing to the Sudanese people is going to tip the balance.

These tariffs may have noble intentions, but the stark reality at the end of the day is that they are just like any other tariff, and will be treated as such by the Chinese and others. There is very little to prevent any country in the world from claiming that the oil the United States buys from the Niger Delta, or from Cabinda Gulf Oil Company, to take two examples, is “stolen” (and a very good case could be made in both instances), and thus slapping a tariff on U.S. goods. The idea that the World Trade Organization would not be sympathetic to Chinese protests, or that it would find these tariffs “as acceptable as the 1990 sanctions that kept Iraq from selling stolen oil from Kuwait,” seems wishful thinking. What this analogy fails to take into account is a lingering international post-Westphalian consensus about sovereignty and territorial integrity that sees invasions and occupations as dangerous acts of aggression, and therefore far more objectionable than business arrangements with controversial regimes. The fact is that buying Sudanese oil is simply not the same as invading Sudan and stealing its oil. And no one at the WTO is likely to see it that way.

Let me just reiterate in closing that these are questions and queries, rather than a wholesale rejection of the proposal put forth. Dr. Wenar has given us an intriguing and exciting idea to consider, one which, with a little clarification and refinement, could make a great starting point. I look forward to the discussion!

The Resource Curse and Leif Wenar’s “Clean Hands Trust”

Leif Wenar has written a brilliant essay which explains both how we are currently harming the world’s poor and how we might go about righting this wrong. Although he does not use this analogy, his analysis implies that dictators are morally tantamount to slave owners, and those who buy natural resources from them are morally tantamount to merchants who trade guns for cheap, slave-produced cotton. If one buys oil from the political regime in Khartoum, for instance, these funds enable the regime to buy weapons with which it can strengthen its illegitimate stranglehold over the Sudanese people. In recognition of this, the U.S. government has prohibited American companies from trading with the Khartoum regime.

This prohibition is to be applauded, but it is not enough. Problems remain because Americans buy cheap products from China, which is able to produce these goods so cheaply in part because it buys oil from the Khartoun regime. Thus, while we in America may not be dealing directly with the dictators, we are morally tantamount to someone who buys cheap shirts from a merchant who buys cotton from slave owners.

The solution to this problem may seem obvious: Stop buying these shirts. Indeed, if the American government has realized since 1997 that it is morally impermissible to buy oil from the Khartoum regime, then it would for the same reasons appear just as wrong to buy products from countries like China who build products with, among other things, oil purchased from this illegitimate government. Upon closer inspection, however, this may be easier said than done. The problem is that in the current context it is not merely shirts which are morally tainted. The morally polluted products are neither rare nor clearly marked. As Wenar puts it,

Stolen Sudanese oil today percolates through the Chinese economy, becoming part of the Chinese imports that Americans buy every day. Americans right now can’t help dirtying their hands with stolen Sudanese oil when they shop at Target and Best Buy.

Assuming that Wenar is right (as I think he is) to suppose that it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to exist today without sullying one’s hands, it is of no use simply to tell Americans to keep their hands clean; we need to find a way to wash the dirt off. Wenar thus recommends what he labels a “Clean Hands Trust.” The basic idea of this Trust is to find a way to pay the Sudanese people a fair price for the oil that Americans are indirectly using. Thus, if China buys $3 billion worth of oil from the regime in Khartoum, the United States should place tariffs on Chinese imports until they have raised this amount of money, which should then be returned to the Sudanese people.

Here one might object that this requires too much of the American people. After all, not all of the oil China buys will be used in the creation of exports, and not all of its exports will be purchased by America. If only half of the morally tainted oil is dedicated to the production of exports, for instance, and then only half of these exports are purchased by Americans, then it would seem that Americans need only pay $750 million to clean their hands. Continuing the tariffs after the $750 million has been raised would amount essentially to taxing Americans for the sins of the Chinese and the other importers of Chinese products.

Although I think this is a legitimate complaint, I will not press it any further here for two reasons. First, I see no reason why Wenar could not design a slightly more sophisticated Clean Hands Trust which could adequately address these types of worries. Second and more important, I think the real worry is that Wenar’s proposal requires too LITTLE, not too much. To motivate this objection, let us return to the slave analogy I invoked above.

I take it for granted that it is wrong to own slaves, wrong to buy cotton that is inexpensive only because it was picked by slaves, and wrong to buy shirts that are inexpensive only because they were made from this morally polluted cotton. This much seems obvious. But now suppose that the slave owner wanted to right her wrong. Could she satisfactorily clean her hands by subsequently paying her slave for all of the cotton he picked? Could she fully right her wrong by paying the slave enough money to compensate him for twenty years of slave labor? I do not think so.

I concede that the slave owner is morally obligated to make reparations to the slave, but I deny that this would be sufficient to clean the slave owner’s hands. To see why, imagine that the slave owner is exceptionally rich. If a slave owner could effectively right the wrong of twenty years of slavery by paying her slave, say, $4 million, then the slave owner would presumably be morally entitled to choose between paying this $4 million now, or keeping the slave in bondage for another five years and then paying him $5 million. After all, if we suppose that the wrong of slavery can be righted at the cost of $200,000 per year, then the slave owner is well within her rights to continue the enslavement, as long as she pays accordingly after the fact. But surely this is wrong. Presumably the slave owner is morally required to free the slave immediately, no matter how rich she is, and no matter how much money she is willing to pay in reparations in the future. If so, then this shows that compensating the slave after the fact is not enough to clean one’s hands of the sin of slavery.

But notice. If the slave owner cannot clean her hands by paying the slave after the fact, then why should we presume that the person who buys slave-produced cotton from a slave owner can clean her hands by paying the slave after the fact? And if the person who buys morally tainted cotton cannot clean her hands in this way, why think that those who buy inexpensive shirts constructed from slave-produced cotton can clean their hands by subsequently reimbursing the slaves? Thus, while I do not deny that something like Wenar’s trust would be necessary to compensate the Sudanese people for our part in stealing their oil, I am not yet convinced that it would be enough to clean our American hands.

While I have tried to raise some questions about Wenar’s Clean Hands Trust, I would like to close by emphasizing how impressed I am with his proposal. The world is a better place than it might otherwise be because the United States government currently prohibits American companies from trading with the Khartoum regime, and the world would be a much better place still if we went a step further and followed Wenar’s insightful and constructive advice.

—

Christopher “Kit” Wellman is an associate professor of philosophy at Washington University, St. Louis.

To Punish the Guilty

Proposals for policy change very often come from a moral or aesthetic dissatisfaction with the observed facts of life. This is an inevitable starting point. But it is not enough. To arrive successfully at the final destination, at the formulation of a legal proposal acceptable by society, one needs to pass through several other stages. At the second stage, one forms a sample of facts that fits the observed pattern, excluding facts that do not. At the third stage, one checks the facts. Some will be well-known and visible, others less well-known and obscure. Some will be similar to the initial source of dissatisfaction. At the fourth stage, one imaginatively tests the proposal — the candidate solution to the problem — against all facts included in the sample. Only if the desired proposal passes all tests in application to all cases are we able to offer the measure for public consideration and possible acceptance. So let us try to apply this approach to the idea offered by Leif Wenar in his deeply morally motivated article, “We All Own Stolen Goods.”

The first statement, “You very likely own stolen goods,” seems to me obvious and needs little debate.

However, the existence of the so-called “Resource Curse” seems to me unproven and lacking confirming facts. The mere fact of a substantial recent literature that regularly uses the term does not convince me of the validity of the concept; it looks to me like a mythical artifact.

The story of the tyrant Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea could not be more disgusting, but unfortunately it is not unique. We do not have go too far, but need only look at recent events — in Russia, for example — to find many quite similar facts. But with one important correction: Mr. Obiang tends to be rather more modest compared to some of my compatriots in the Russian government and in government-owned and government-related companies.

“Mr. Obiang has just bought his sixth private jet.” Mr. Anatoly Chubais, who manages the half-government-owned company RAO UES, had six jets eight years ago, when its sales and profits were a small portion of what they are today. And this is not to mention the dozens of other companies with private fleets; the government-owned airline Rossiya now has about a hundred jets.

“Mr. Obiang’s son prefers Lamborghinis.” To say that every second high-ranking bureaucrat in Russia’s Federal Security Service, Customs Service, Constitutional Court (sic!) in Moscow drives either a Lamborghini or Porsche would be a slight exaggeration, but probably only a slight one.

Malnutrition in Mr. Obiang’s country is not disputable. From 1998 to 2005, average life expectancy for men in Equatorial Guinea fell by 2.1 years, while the total population from 1999 to 2007 increased by 23%. Nevertheless, over a corresponding period of time, Russia’s male life expectancy fell by 2.4 years, while the total population of the country decreased by 3.7%.

“Mr. Obiang is killing or menacing his opponents.” What has happened with Anna Politkovskaya, Alexandr Litvinenko, dozens of Russian journalists, 331 hostages in the Beslan school, 130 hostages in the Nord-Ost theater siege in Moscow due to efforts of governments troops and with hundreds of thousands Russia’s citizens in Chechnya is well known as well.

Mr. Obiang has been proclaimed “the country’s God.” Mr. Putin has been proclaimed “the national leader.”

The list of similarities can be continued, but the main idea seems to be clear enough. If Prof. Wenar’s proposal for the approach toward Equatorial Guinea and Sudan is accepted, why should it not be applied toward Russia as well?

Another set of problems arises with his suggestion to use the Political Rights Index produced by Freedom House. True, this is probably the best indicator today of the political control citizens have over those who hold power. Nevertheless, the index is not free of shortcomings, which are admitted even by its authors. The index’s problems are due to the fact that it is based not on hard but soft data, produced by a collection of opinions rather than objective facts. Therefore, critics might reasonably argue that it could be manipulated in order to receive a desirable political score — for example, for a fraction of the expected gains.

The other issue is that the list of the worst countries (probably better to say: “regimes”) with the score “seven” — Myanmar, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan — is not final. Among the regimes omitted from Prof. Wenar’s article are not only the rather anti-American political regimes in Uzbekistan, Syria, and Cuba, but also the America-neutral ones in Zimbabwe, Turkmenistan, Vietnam, and the quite American-friendly one in Saudi Arabia. The last country is also one of the main suppliers of oil for the United States. What about the application of the measures of the “Clean Hands Trust” against those regimes, including the one in Saudi Arabia?

“Seven” in the Freedom House scale for political rights of citizens is a really bad score. But a score of “six” was posted for countries such as Iran, Oman, Qatar, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Angola, Azerbaijan, Cameroon, Tunisia, Gabon, Congo, Chad, Brunei, and Algeria, and “six” is not much better. Should these countries be excluded from the list? Should they go on it? What about countries that score “five”? We could continue until eventually we ask ourselves: where to put the borderline? And it is impossible to avoid the last, but not the least, question in this section: Should the “Clean Hands Fund” be applied only to Equatorial Guinea and Sudan, or to all the above-mentioned countries? And what will the scale of its operation imply?

Dictatorship is dictatorship, always and everywhere. Revenues derived from the national economy — including natural resources — are spent on luxury goods, redirected to the army and police, spent on security apparatus and warfare, and piled up in tax havens from Switzerland to exotic tropical islands. The amounts have multiplied over a short period of time in many of the above-mentioned countries. What is the source of this money? The statement given by Prof. Wenar is straightforward and simple: “This is literally theft.” Why theft? Theft from whom? Whose property was it before it was “stolen”? The answer offered is straightforward again: “The natural resources of a country belong to its people.” This is, from my point of view, the weakest link in the whole chain of the author’s logical construction. With all due respect to Mr. Bush’s statement about the rightful owners of Iraq’s oil, this does not seem that strong an argument in the context of a serious legal debate. The views of Hugo Chavez and Ayatollah Khamenei will not help much, either. Article 1 of the primary human rights treaty, which says that “All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources,” may be even less convincing.

Mr. Obiang and Mr. Putin, as well as many other similar figures, could claim that they, too, are people of their respective countries and, therefore, natural resources must belong to them. Moreover, since governments and states are representative bodies of the people, governments and their leaders could easily argue that they have a stronger legal claim to the country’s natural resources than anybody else. According to them, since all the people of the country cannot actually physically own and manage their countries’ natural resources, this “heavy burden of owning the assets” must be placed on the shoulders of government. And since governments are also too large to manage resources effectively, the “right” and “best” people to do it will probably be the leaders of the government, or their designated representatives, who just by coincidence turn out to be their relatives, buddies, closest friends, partners, and colleagues.

It is not a huge revelation to say that, here in the real life of the modern world, many tyrants, dictators, authoritarian leaders, scoundrels, and swindlers of all kinds maintain that what has been laid out above is the most basic, sensible, and attractive principle of resource ownership. Tyrants prefer to see the natural resources of their countries proclaimed as belonging to all the people. Why? Because when translated into practical political language, this really means that resources must be nationalized, government-owned, and government-managed. It means that resources must be controlled and used by us, the beloved leaders. In other words, the principle of the national ownership of natural resources deeply embedded in international law in reality is not a solution to the problem that attracted Prof. Wenar’s attention, but is instead its true and deepest cause.

This failure to identify the real problem leads the author to mention, among other options, a faulty solution: the proposal to create a so called “People’s Fund,” “a mutual fund built up by auctioning the country’s natural resources, from which any citizen could at any time withdraw their per-capita share of the revenues.“Instead of solving the problem of ineffective use of natural resources with their privatization, another problem is added — the ineffective use of resources accumulated in the “people’s,” “national,” “nationalized,” “state,” “state-managed,” and similar funds. Problems are not being eliminated, but multiplied.

The most “promising” strategy proposed by Prof. Wenar, to take legal action in U.S. jurisdictions against middlemen who trade “stolen” resources, seems to me not only impractical, but also as moving against fundamental principles of free trade.

Another proposal — creating a “Clean Hands Trust” against natural resources exported from countries with tyrannical regimes — immediately raises many questions. For example, why should the Trust cover only natural resources? What about other goods? What about services? If the answer is positive, and tariffs are to be raised against all goods and services imported from a country with a particularly tyrannical regime, what is the difference between the proposed measure and traditional economic sanctions? Their ineffectiveness is well known.

Another set of questions can be raised regarding the fairness of punishing private entrepreneurs who are citizens of a country facing tariff sanctions. In addition to the suffering caused by their own political regime, it seems that those business people will be punished again by sanctions from the United States. Would that be fair? And would this really accelerate desirable change within the tyrannical regime?

If the proposed tariffs are to be raised just against government companies or the leaders of tyrannical regimes, it would be better to make that clear. But in that case it would be helpful, first, to widen and “smarten” the possible range of sanctions, including issues of visas, entries into democratic countries, bank accounts in states with the rule of law, etc. And, second, to exclude natural resources from the objects of those sanctions’ application.

If someone is guilty of stealing national resources — of grabbing public money, destroying freedom and democracy, and violating the rights and property of the people living under repressive regimes — it is not really about oil. It is not really about gas or diamonds. It is not really about natural resources at all. It’s not about goods, or services.

If someone is guilty of stealing resources, the issue is not what is stolen, but rather who is stealing. Our focus ought not to be on the objects of theft, but on its perpetrators. If the purpose of Prof. Wenar’s proposal is to punish someone, it is better to punish those who are really guilty, not those who are most accessible or convenient.

—

Andrei Illarionov is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute.

The Conversation

Living Up to Our Principles

Many proposals for reforming the global order ask us to accept new legal principles — for example, to accept that countries have the legal right to launch preventive wars when they believe their security is threatened. Other proposals ask us to build new international institutions — for example, to create a world court with compulsory jurisdiction over all states and persons.

The resource curse initiative is different. This initiative works on principles that are already widely accepted and deeply held, such as the principle that theft is illegal and wrong. To enforce such principles it proposes to utilize familiar institutions like national courts and trade regimes. If the resource curse proposal is surprising at all, this comes from seeing how world trade violates our principles in rather shocking ways and seeing that we can fix this with the institutions we have.

What sends stolen goods into our gas stations and shopping malls is an unmistakable flaw in global markets: the “might makes right” rule that makes a mockery of the rights of property. Once this flaw is pointed out, one can see that correcting the flaw is not really a question of whether we’ve found the right principles or the right institutions, but primarily a matter of whether we can summon the political will to do so. What’s going on now is clearly wrong; the question is whether we will stop it.

My experience has been that the more people hear about this initiative’s premises and proposals, the more compelling they seem. I’m grateful to the three Cato Unbound respondents for raising issues that will allow more of the initiative to be explained than was possible in the original article. Those looking for a full formal presentation of the initiative for ending the resource curse can find the more scholarly papers here.

Property Rights

The resource curse initiative is based entirely on property rights. Property rights are now being violated on a massive scale, and this must be stopped. As in neighborhoods where property rules are regularly breached by protection rackets and robbery, in resource cursed countries the failure to enforce property rights leads to a tremendous amount of misery. Yet the basis for the legal argument is not sympathy, but property. The first principle of capitalism is that property rights must be enforced. The initiative’s central demand is that we enforce property rights in the system of global trade, instead of allowing and in fact encouraging massive theft of natural resources.

To use existing institutions to enforce property rights we need not endow these rights with any new extraterritoriality, as John Ghazvinian worries. Property rights are already global. In your cell phone there is likely a highly conductive mineral called coltan. That coltan in your cell phone may well have been dug out of the Democratic Republic of Congo by villagers enslaved by extraordinarily brutal “private militiamen.” These militiamen trade coltan for cash, which they use to buy more machine guns and machetes to force more coltan mining. Despite the history of that mineral in your pocket, the police and courts of your country will now affirm and protect your property rights in your cell phone, including your property rights to that coltan.

This is an example of how national legal systems already recognize and enforce property rights in goods that cross international borders. This is how it must be — global capitalism could not work if property rights were not in this way global. The flaw in the trade system as it is now is at the first step — the step with the militiamen. The flaw is when the “might makes right” rule vests property rights in whichever local actors can be the most ruthless or terrifying. That first step is the flaw that any market system worthy of the name must correct. Once the “might makes right” rule is eliminated from the system of global trade, you will be able to buy a cell phone (and a laptop, and a video game console, etc.) with the confidence that what you are buying has not been taken illegitimately from resource cursed countries, and that your money will not be going back to fund the men with guns.

National Ownership

One major principle in the proposal to end the resource curse is that the citizens of each country own the resources of their country. As mentioned in the main article, this principle is regularly affirmed by world leaders from all parts on the political spectrum. It is also asserted in primary treaties of international law. The principle thus has the same kind of standing in international law as, for example, the human rights law prohibiting slavery, the Geneva Conventions, and the treaty that established the WTO. The primary international law affirming national ownership has been in effect for a long time, and has been ratified by the vast majority of the nations of the world (including the United States and all of the other G8 countries). This law is one of the central pillars of international law.

Although the principle of national ownership might sound surprising when stated outright, most people (except some anarchists and radical global egalitarians) find that when they hear what the principle means they believe it already — and in fact they believe it rather firmly. The principle of national ownership is a deep part of the framework we use every day to understand the politics of the world.

The principle entails that America’s resources belong to the American people, Canada’s resources belong to the Canadian people, Egypt’s resources belong to the Egyptian people, and so on. The oil, for example, off of the U.S. Gulf Coast belongs to the American people. If it were found that Cuba had drilled a long diagonal pipeline through the Gulf of Mexico and was now siphoning American oil from the Florida coast, the American people would immediately (and perhaps literally) be up in arms. The oil within the territory of the United States is American oil, and foreigners must not take it without permission.

Similarly, national ownership explains our rejection of unilateral private seizure of a country’s resources. In the years leading up to the Reagan administration companies such as Shell discovered large oil deposits off the coasts of Florida and Louisiana. One can imagine the response had President Reagan secretly sold this oil to Shell, then put the profits from these sales into his private bank account and ordered the FBI to detect and squash any dissent. America’s natural resources must not be disposed of in ways that wholly bypass the assent of the American people. Yet selling a country’s resources while bypassing the people is just what Obiang, the dictator of Equatorial Guinea, is doing today.

One key to understanding the national ownership principle is seeing how permissive it is. The principle does not, as Andrei Illarionov says, require that a country’s oil must be “nationalized, government-owned, and government-managed.” (Remember, the principle of national ownership is affirmed by George W. Bush.) In fact the principle is entirely compatible with most or even all of a country’s natural resources being privately owned. All that the principle requires is that any laws which regulate private acquisition of natural resources in a country be validly enacted when a minimally decent government is in place. Obiang’s government is not close to being minimally decent, so Obiang cannot enact laws that legitimately transfer Equatorial Guinea’s oil to him. Yet when the U.S. Congress initiates public auctions among corporations for oil-drilling leases in American coastal waters (as it has done for the past 25 years), it is starting a process whereby America’s oil legitimately passes into private ownership. This is how resource management works day-to-day in the United States right now. No one in American politics gives the underlying national ownership principle a second thought.

All of these conclusions about national ownership go almost without saying. The principle of national ownership is — as one would expect of a principle that had been endorsed by most nations — adaptable to many different economic systems, and widely morally attractive. It is a flexible standard that forbids only the most flagrant injustices in natural resource management. Unfortunately there is a great deal of flagrant injustice today that violates the principle of national ownership, which persists mostly because the world has not yet focused its attention on it.

Minimally Decent Governance

Ending the resource curse means stopping bad actors from controlling national resources by might instead of right. To do this we need to know from which countries resource sales are illegitimate — which countries are suffering political conditions that are so bad that the citizens could not possibly be authorizing their resources to be sold out from under them.

The property rights approach to the resource curse uses the Freedom House ratings. Freedom House is an NGO that publishes a highly respected index of the political conditions in every country in the world. The lowest Freedom House ratings describe political conditions in which the people of a country could not possibly be either aware of or in control of what’s happening to their country’s resources.

The Freedom House index assigns each country a rating from 1 (best) to 7 (worst) on civil liberties and on political rights. The index on civil liberties measures to what degree citizens are free from arbitrary political coercion, violence or manipulation. The report describes countries with the worst two scores on civil liberties in this way:

Rating of 6: People in countries and territories with a rating of 6 experience severely restricted rights of expression and association, and there are almost always political prisoners and other manifestations of political terror. These countries may be characterized by a few partial rights, such as some religious and social freedoms, some highly restricted private business activity, and relatively free private discussion.

Rating of 7: States and territories with a rating of 7 have virtually no freedom. An overwhelming and justified fear of repression characterizes these societies.

Among the countries rated 6 on civil liberties in the 2008 Freedom House report are Iran, Syria, and Zimbabwe. Among the countries with a rating of 7 are Burma, North Korea, Somalia, and Sudan.

The Freedom House index of political rights measures how much the people’s informed and unforced choices control what those with power in the country do. The descriptions of countries that receive the worst scores on political rights are as follows:

Rating of 6: Countries and territories with political rights rated 6 have systems ruled by military juntas, one-party dictatorships, religious hierarchies, or autocrats. These regimes may allow only a minimal manifestation of political rights, such as some degree of representation or autonomy for minorities. A few states are traditional monarchies that mitigate their relative lack of political rights through the use of consultation with their subjects, tolerance of political discussion, and acceptance of public petitions.

Rating of 7: For countries and territories with a rating of 7, political rights are absent or virtually nonexistent as a result of the extremely oppressive nature of the regime or severe oppression in combination with civil war. States and territories in this group may also be marked by extreme violence or warlord rule that dominates political power in the absence of an authoritative, functioning central government.

Among the countries rated 6 on political rights in the 2008 report are Angola, Iran, and Rwanda. Among the countries rated 7 are Burma, Equatorial Guinea, North Korea, Sudan, Syria, and Zimbabwe.

There are other respected rating scales that can also be drawn on (and that tend to rank countries in the same order as Freedom House). We use the Freedom House ratings because they are best for a feasible initiative for reform. The Freedom House ratings are used for official purposes by the U.S. government, and so have enough standing to be introduced into litigation and into trade policy. We also use them because unlike “bottom 10%” ratings they are absolute instead of relative — it is possible (and highly desirable) that the world will someday contain no 7s.

We can be certain that countries which rate a Freedom House 7 on either civil liberties or political rights are countries in which the people could not possibly be authorizing their resources to be sold off. This is evident from the characterization of 7s above. We should take action against the 7s, because we can be sure that resources coming out of these countries are being sold illegitimately.

Naturally the use of any such index will also raise questions. Illarionov asks: where should we draw the line? If we sanction the 7s, why not also the 6s too? Indeed, as his examples show even large countries like Russia experience the corruption that comes from the resource curse (Russia in 2008 is a Freedom House 5 on civil liberties and a 6 on political rights). How far up the scale should we go?

This answer to this question is analogous to the answer to the more general question about which human rights we should enforce. On human rights we say: some human rights are controversial, but this should not stop us from acting where we are sure a grave wrong is taking place. We should act where we are certain there are violations, while we continue to work out our responses to harder cases. If some regime is engaging in genocide or ethnic cleansing, then other governments should act. Governments need not — indeed they should not — wait to act against genocide until they have also reached consensus as to whether, for example, there is also a human right to democratic participation. We should stop the worst even if we haven’t already entirely agreed on what is the best.

In the case of the resource curse, stopping the worst will in fact stimulate positive action and greater consensus on how far up the scale to go. Resource sales from the 7s are clearly illegitimate. Stopping these will make those with power in countries rated 6 feel less secure about their right to transfer resources, and so will give them strong incentives to improve political conditions in their countries so as to climb up to higher, safer levels on the scale. And the enormous global pressure to stabilize a legally secure and predictable system of resource transfers will give strong incentives for all trading nations to reach an agreement concerning what level of ratings is sufficient for resources sales to be legitimate. Future agreement on a minimum rating (be it 6 or 5 or some other score) is certain to lead to a tremendous improvement over the current situation, since now there is no minimum rating for legitimate resource sales at all.

Yet with so much at stake, can we really trust the Freedom House ratings to be accurate? Ghazvinian worries that pressure would be put on Freedom House to alter its ratings so that resource sales from particular countries was either permitted or forbidden. This is certainly a serious concern, and any feasible proposal must face it. One solution would be to diversify the index used to include other rating scales, such as the Bertelsmann Transformations Index, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, and so on. But let us stay just with the Freedom House standard for now, and see what can be said in response to Ghazvinain’s worry.

There are reasons to be optimistic that even Freedom House alone could resist pressure and live up to its self-image as an objective and independent evaluator of political conditions. One thing we know for certain is that the current (2008) Freedom House survey is not warped by political pressures of the type just mentioned. Neither the present U.S. administration nor large American corporations have realized that the Freedom House scores call the legitimacy of natural resource sales into question. This can be confirmed by the fact that several countries (e.g., Equatorial Guinea, Libya) with whom American companies have signed large contracts have ratings of 7. Given that the current ratings are not distorted by the pressures that concern Ghazvinian, and that everyone would know that pressure would be applied on Freedom House to revise its ratings upwards for certain countries, much of the organization’s reputational credibility would turn on its proving publicly that upward revisions of the ratings for those countries were justified. Moreover, academics and non-governmental organizations will scrutinize and criticize each new annual survey, increasing the pressures on the organization to resist surreptitious suasion from outside.

Moreover, the full implementation of the resource curse initiative should keep Freedom House from being captured by interest groups wanting to skew the ratings. To see why, consider again Sudan. Sudan is currently rated a 7 on both Freedom House scales, so the U.S. government should set up tariffs against China and a Clean Hands Trust for Sudan as the main article describes. The big oil companies will want to make contracts with the Khartoum regime, so may wish to pressure Freedom House to raise its scores for Sudan. However, the manufacturing interests who are protected by tariffs against China, as well as the banks that are holding the Sudanese funds in trust, will very much want the tariffs and the Trust to stay in place — and so these powerful interests will wish to exert counter-pressure to the oil companies so that the ratings stay low. The property rights approach to the resource curse generates incentives that balance power with power, which can empower Freedom House to resist capture by either side.

The Anti-Theft Tariffs and the Clean Hands Trust

Robert Nozick once claimed that taxation of earnings from labor is on a par with forced labor. Christopher Wellman uses similar imagery to describe the resource curse: “Dictators are morally tantamount to slave owners, and those who buy natural resources from them are morally tantamount to merchants who trade guns for cheap, slave-produced cotton.” Many readers will find Wellman’s framing of the issue compelling and his arguments sound. Certainly there is no reason to resist Wellman’s conclusion that a just market order requires more than the reforms that the property rights approach requires.

Wellman makes one suggestion, however, that may rest on a misunderstanding of one proposal. He characterizes the trust-and-tariff mechanism — which would, for example, subtract the value of stolen Sudanese oil from Chinese imports to the US and hold this money in trust for the Sudanese people — as a means for the American people to reimburse the Sudanese people for a wrong the Americans are doing to them. Handing over the funds in the trust would be, Wellman suggests, a kind of compensation — a way for Americans to clean the hands that they have soiled by buying Chinese goods made with stolen oil.

Yet the moral force of the trust-and-tariff mechanism is not to compensate, but rather to prevent complicity. The anti-theft tariffs stop at the border that portion of the Chinese imports that the Sudanese can claim as their own. The money from these tariffs goes straight into the trust, and will be given back to the citizens of Sudan once they can install a government better than the one now afflicts them. The value of the goods stolen from the Sudanese never reaches the American people — the point of the trust is to prevent American consumers’ hands from becoming dirty, not to wash the stains out thereafter. With the tariffs and trust in place consumers can buy with assurance that they are neither benefitting from nor incentivizing the theft of natural resources from poor countries.

Whether the trust-and-tariff mechanism would be effective in deterring states like China from buying resources from the worst regimes is of course a separate question. Illarionov notes that sanctions have often been ineffective in changing regimes’ behavior, and in this he is clearly correct. The problem with previous sanctions is that the sanctions have not been universally observed. Oppressive regimes have sold their countries’ resources to their traditional patrons and to other repressive regimes, thereby escaping some of the pressure that the sanctions attempted to apply.

The biggest difference between the property rights approach and previous international sanctions is that the trust-and-tariff mechanism creates a better alignment of incentives and so is more likely to work. The property-based approach gives all potential buyers incentives not to trade with an oppressive regime. Those who do trade (e.g., China with Sudan) will face exactly proportionate trade penalties. Unlike traditional sanctions, trade penalties here track the looted natural resources, so no one receiving these resources will remain unpenalized.

Of course, as Ghazvinian says, many lawmakers in countries like the United States are unlikely to embrace any proposal that uses tariffs to achieve political ends, and will be unlikely to “put noble ideas ahead of a free-trade agenda.” This is certainly true, yet this concern does not touch the resource curse proposals in the least. The trust-and-tariff mechanism is designed to further legal ends, not political ends — it is designed to enforce property rights within the global market system. Lawmakers can hardly be indifferent to the legal enforcement of property rights: property rights are the foundation of the market order that America has benefitted so much from, and has done so much to spread across the globe. The trust-and-tariff mechanism is not a political stratagem, it is a law enforcement mechanism. It is no more or less noble than a police officer stopping a thief from fencing his loot — it is no more or less noble than the market itself, and the rule of law that maintains it.

This cannot be overemphasized: the anti-theft tariffs and the Clean Hands Trust do not conflict with a free-trade agenda. They are a free trade agenda. Complaining that this mechanism would limit free trade in resources is like complaining that our stopping a Mexican-based forced prostitution ring would limit free trade in persons. It is not free trade that currently brings billions of dollars of stolen resources across American borders — indeed, it is not trade at all. These resources are being extracted from their countries through severe coercion and violence, and those who pass these resources to us have no valid title to them. These resources come to us not from free trade, but from theft. The trust-and-tariff mechanism will end our participation in the extraction, sale, and receipt of stolen goods, and will help to create a global commercial system in which all resource transfers become free trade.

An Invitation

These remarks have already gone to some length, and several of the respondents’ concerns are still on the table. The issues of WTO regulations and Chinese retaliation, for example, are still to be explored. Instead of going further now, let me again express appreciation for the respondents’ searching scrutiny of the premises and proposals of the resource curse initiative. Successful proposals for reform like this one need the critical attention of sharp experts of good will, which Mr. Ghazvanian, Dr. Illarionov, and Prof. Wellman certainly are. If others with expertise or just good ideas wish to offer more criticisms and constructive suggestions for the initiative of course these will be very welcome. I look forward to the continuing conversation at Cato Unbound, and can also be reached for personal communication at the email address on the webpage above.

Many of the great movements for moral progress in the past two centuries have been morally simple. All humans should be free: the hard work was forcing the end of slavery. All nations should be free: the hard work was dismantling European colonialism. The resource curse is also morally simple: it violates property rights on a massive scale, and it causes enormous suffering. Yet ending the resource curse should be — in comparison to these other movements — relatively easy. The destructive “might makes right” rule is obviously as corrupt as slavery and colonialism. And the levers we can pull to revoke it are already close at hand. We need merely to affirm our own principles, and then to pull those levers. It is only a matter of acting together to do what we already know is right.

Stolen Goods and Dirty Hands

In his recent post, Leif Wenar explains why he thinks I have misunderstood his proposal. In particular, he contests my view that the trust is designed to clean our dirty hands. He writes,

the point of the trust is to prevent American consumers’ hands from becoming dirty, not to wash the stains out thereafter. With the tariffs and trust in place consumers can buy with assurance that they are neither benefitting from nor incentivizing the theft of natural resources from poor countries.

As long as we are buying stolen products, however, it seems to me that our hands must be dirty — no matter how much we put in a trust. If I buy from Jill a bicycle that I know she stole from Jack, then it strikes me that my hands are dirty. If this is correct, then it seems equally true that my hands would be dirty if I buy oil (or products made with the oil) a dictator has stolen from her constituents. To counter this, it appears that Wenar must defend at least one of three claims: (1) buying a bicycle from Jill, which she has stolen from Jack, does not dirty one’s hands, (2) one can buy a stolen bicycle without soiling one’s hands, as long as one also pays the rightful owner of the bicycle the fair value of this bike, or (3) there is some morally relevant difference between a person’s bicycle and a people’s natural resources which explains why one cannot purchase a stolen bicycle without dirtying one’s hands, but one can buy the stolen resources without ever getting dirty hands. None of these three options seems plausible to me.

Inviting an Endless Cycle of Tit-for-Tat Tariffs?

There are some fascinating discussions going on here, and an embarrassment of riches when it comes to potential directions to take the conversation. One barely knows where to jump in. At the risk of being unimaginative, I’d like to return to a couple of the nuts-and-bolts practical questions I raised in my original reply. In particular, I’d like to posit a scenario and hear what you all think of this.

Let’s for a moment forget about Sudan, where American companies are already forbidden from operating. Let’s instead take Equatorial Guinea. We all agree this is one of the world’s most unpleasant governments. We all agree that “theft” is not an overly enthusiastic label to attach to the actions of Obiang. We don’t need Freedom House to tell us this. But who is actually buying Equatorial Guinea’s oil? The Chinese, to some extent, but largely it is the United States. And who are the oil companies operating in Equatorial Guinea? ExxonMobil, Amerada Hess, Marathon, and a host of smaller American independents account for virtually all of Equatorial Guinea’s exploration and production activity. And when that oil arrives in the United States, it is refined and sold as fuel for powering the American economy, or it makes its way into various stages of the American manufacturing industries.

Now, let us say we have just passed the Clean Hands Trust reforms that are being proposed. It is suddenly impossible to escape the conclusion that we here in the United States are producing products for export that have been made with “stolen” crude oil from Equatorial Guinea. So what now? Who is going to introduce a tariff on American products? Will it be the Chinese, who clearly are going to have worked up a nice healthy appetite for retaliatory action following the whopping tariffs we’ve just imposed on them over Sudan? Will it be Venezuela? Will it be a Russian government keen to make a political point about U.S. “hypocrisy”? Or, perhaps most worryingly, will it be some nice European government that — quite reasonably — is uncomfortable with the idea of one standard being applied to China and another one to the United States?

Perhaps I am being too much of a Chicken Little. I am prepared to accept Dr. Wenar’s point that this proposal is meant to provide incentives for good behavior, rather than create a world trade environment burdened by a host of new tariffs. Indeed, perhaps I am being unduly blinkered in my approach, and ignoring the fact that there is a clear moral imperative here. Perhaps I would feel differently if we were talking about actual human slavery here, and perhaps I am skeptical only because I happen to feel the “genocide” label is not an accurate one to apply to the situation in Darfur (but that’s clearly a separate discussion). However, I just can’t help feeling that, in the cold hard light of day, we are simply inviting an endless cycle of tit-for-tat tariffs introduced in a highly politically charged atmosphere in which every country has a slightly different idea of whose hands are and are not “clean.”

I also still think that once you start to move more than one or two steps away from the “scene of the crime,” as it were, it becomes very difficult to make a moral case for punishment. I admit I am way out of my depth talking about moral philosophy, though, and Kit Wellman will probably set me straight on that. Ultimately, I suppose, I tend to agree with Andrei Illarionov that if we can establish that someone has committed a crime, then we should make it our priority to find a way to punish the actual criminal — rather than devising a complicated scheme that is potentially disruptive to global trade, in an (admittedly noble) effort to punish the people buying and selling goods that happen to have been manufactured using some small element of “stolen” material. But again, I am prepared to be convinced that I am being overly cautious here.

Multiple Thefts, Multiple Tariffs

I agree with John Ghazvinian’s claim that Teodoro Obiang deserves to be punished for his tyrannical rule over the citizens of Equatorial Guinea. Indeed, given that these citizens are obviously in no position to do so themselves, Obiang strikes me as an ideal candidate for international criminal prosecution and punishment. But one can concede all of this without denying Wenar’s core point that Obiang has no valid title to the country’s oil deposits, and thus one should not buy oil from him. It seems to me that the very same reasoning that the American government has invoked to prohibit American companies from buying oil from the regime in Khartoum applies to Obiang. As a consequence, we ought not to be buying stolen oil from Obiang, and (as Ghazvinian points out) the Russians would be justified in putting tariffs on our exports as long as we do. Thus, like Ghazvinian, I suspect that the logic of Wenar’s reasoning might well lead to a proliferation of tariffs. But it is not clear to me that this constitutes a reductio of Wenar’s position. If there are multiple countries buying stolen resources from illegitimate rulers, then why not have multiple tariffs designed to repay the various victims of the initial thefts?

Who Are We Punishing?

Since I haven’t heard much response, either positive or negative, to Christopher Wellman’s suggestion that we have multiple tariffs for multiple thefts, I will make the assumption that everyone accepts this would be a natural outcome of the original Leif Wenar proposal. In other words, I think we can all agree that we are likely to face a situation in which both American and Chinese goods (and probably the goods of several other important nations) are subjected to stiff tariffs in the international marketplace.

Is this something we are all comfortable with? I take Dr. Wenar’s point that this is a mechanism designed to further legal rather than political ends, and I can appreciate that the intention is to punish theft, and therefore to honor the sanctity of free trade. But it still seems to me that the net result, whatever the intention, is to create a politically charged environment in which everyone is slapping tariffs on everyone else, and the global economy grinds to a halt (or at least a serious slowdown).

Perhaps this is an acceptable price to pay to live in a world in which justice and fairness are our principal touchstones. Perhaps. But I have to admit, at the moment, I am unconvinced. And the main reason I am unconvinced is because this feels to me like we’re not punishing thieves, and we’re not even punishing those who traffic in stolen goods, but rather we’re punishing those who happen to live in countries whose economies happen to depend in part on buying and selling goods that may have been produced from stolen goods. And that feels to me a bit like asking your grandmother to pay war reparations to the Iraqi people because she happens to hold some shares in Halliburton. Why not just go after Dick Cheney?

Sound Policy Is Based on Sound Principles

The discussion of Leif Wenar’s lead essay, “We All Own Stolen Goods,” and his follow-up comment, “Living Up to Our Principles,” have clearly exposed some problems with the principles (referred to regularly in both entries, and even in the title of one of them) used as the basis for his policy proposals. I think this is a good place and time to formulate (actually, to remind us of) some principles for public policy initiatives widely shared, accepted, and tested.

Follow the procedure. The aesthetic rejection of the disgusting behavior of a dictator is a natural starting point. Nevertheless it is still far from the final stage. To arrive at the successful implementation of an exciting new idea, one needs to pass through all the necessary stages of its analysis and testing.