Benjamin Barber’s book Consumed is a fascinating piece of anti-market rhetoric. However, it fails to provide almost any evidence at all for any of its conclusions.

Barber makes what we call a “corruption” objection to markets: he claims that 1) commodifying various goods and services, and 2) exposure to markets in general tends to harm our and our society’s character in various ways. Consumerism “infantilizes” adults. Markets draw us away from the civic forum and to the market; they reduce civic participation. Markets induce us to have a narrow-minded conception of liberty. They reduce important forms of diversity. They cause us to lose meaning.

These are all social scientific or empirical claims. Philosophical analysis, or the tools of political theory, can at best help us fix or make clear various definitions of terms and concepts. For instance, philosophy can help us determine which of competing conceptions of liberty might be better. But to establish that one thing causes another, you need the tools of the social sciences. Yet while Barber makes a series of extravagant causal claims in his book, he neglects proper social scientific methods. There’s a reason why none of the chapters were first published in the American Political Science Review—he doesn’t meet even minimal standards of evidence.

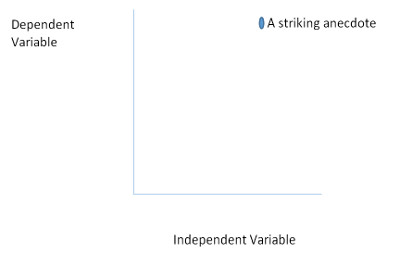

Instead, Barber’s main mode of argument is to first assert a strong causal claim (e.g., markets cause us to adopt a misguided liberal conception of liberty rather than a superior democratic conception), and then try to prove that claim either by 1) citing other theorists who assert it without evidence, or 2) by providing illustrative anecdotes. But as anyone who has taken a graduate-level methods class in political science or econometrics knows, a few anecdotes are insufficient to establish causal trends. Consider the figure below:

In the figure above, there is no statistically significant relationship that can be inferred between what I’m calling the “independent” and the “dependent” variables. Any line one draws will be statistically insignificant. Even if I added two or three more anecdotes, these still would be insufficient data to make any claims about correlation. Correlation is not sufficient to show causation, but non-correlation is almost always sufficient to show non-causation.

This is one of Barber’s essential problems. He doesn’t even get as far as making the undergraduate mistake of inferring causation from mere correlation. Rather, he fails to show us there is even correlation. For example, Barber claims that markets tend to corrupt us by eroding civic virtue in various ways. His main argument appears to go something like this:

The Civics Objection

- Markets encourage citizens to think of freedom as the ability to fulfill their own desires rather than to think of freedom as political autonomy.

- Therefore, markets encourage citizens to retreat from common civic life.

- Therefore, markets undermine civic virtue.[1]

There are lots of problems with this argument. One is philosophical: Barber seems to have an overly narrow conception of civic virtue. But let’s put that aside. Even if we grant Barber’s his narrow view of what counts as civic virtue, he doesn’t establish either of his two premises.

Barber doesn’t actually give us any evidence that markets cause citizens to think of freedom as the ability to fulfill their own desires rather than to think of freedom as political autonomy. What Barber mostly does, instead, is to cite a range of political philosophers and economists who are friendly to markets, and who themselves advocate thinking of freedom as the absence of interference. He also notes that many people living in market societies accept this conception of freedom, though he does not provide us any interesting stats showing whether or not these conceptions of freedom are highly correlated with market societies. Moreover, Barber does not show us that living in a market society causes people to think this way. For all we know, consistent with the evidence he provides, people adopt market institutions because they already think this way. Or, perhaps (A) people accepting idea of freedom as the absence of interference and (B) people being friendly to markets have a common cause, (C).

We also don’t see any empirical evidence from Barber that market societies actually undermine citizens’ participation in democracy. Barber believes that markets draw us away from the forum and public life and into private concerns. But, again, he doesn’t provide proper evidence this is so. We might try to test this thesis by seeing whether more marketized societies have lower rates of political participation. To that end, in our book, Peter and I look at standard measures of voter turnout for the world’s democracies and then plot these against the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom rankings. We find a very slight but statistically significant positive correlation: all things equal, the more capitalist a society is, the higher voter turnout it has. We note in the book that this is not sufficient to prove for sure that markets do not reduce participation, but still, we’ve brought a knife to what’s supposed to be a gun fight, but in which the other party came unarmed.

For someone who decries consumerism and the supposed anti-intellectualism of capitalism, Barber is a strange and ironic character. He’s a member of the political science profession, but seems to have no respect for the basic methods of the field. Ironically, it seems like Barber is happy to violate standards of evidence or norms of argumentative rigor… for money and fame.

Note

[1] Benjamin Barber, Consumed (New York: W. W. Norton and Co, 2008), pp. 131-32.