A number of people who read my original essay interpreted it as a defense of experts’ right to tell individuals how to live their lives. This is a good time to set the record straight. Here goes…

In one of my all-time favorite songs, Morrissey says:

So…the life I have made

May seem wrong to you

But, I’ve never been surer

It’s my life to ruin

My own way

If I were giving expert advice to an individual about how to run his life, I’d heed this reply—even if I knew for sure what was best for the individual in question.

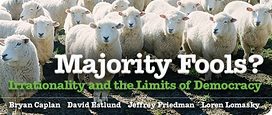

But when the majority asks for the same latitude, it’s a very different story. The majority isn’t just asking for the freedom to makes its own mistakes. It’s ordering all of us to pay for its mistakes. If the majority supports price controls on gasoline, for example, we all have to live with the shortages, the lines, and the other inefficiencies.

You can say that it’s arrogant for experts to try to overrule the majority on this basis. But would it be fairer to say that the majority was arrogant to impose its folly in the first place?