Jerry O’Driscoll’s wide-ranging lead essay valuably introduces several important themes for discussion. I will here examine in more detail the historical record of the Federal Reserve System. The examination validates O’Driscoll’s characterization of the Fed’s record as “unenviable.”

The Federal Reserve Act was passed in December 1913. The Act did not assign the Fed any responsibility for monetary policy, because the gold standard was supposed to continue to govern the quantity of money in the U.S. economy. The twelve Federal Reserve district banks were expected only to be adjuncts to the banking system (bankers’ banks, lenders of last resort, and regulators of their member banks), and the Board of Governors basically an oversight body. The act did empower the Reserve Banks to issue banknotes, but it did not exclude the continued issue of notes by commercial banks, and it placed a 40 percent gold reserve requirement against Federal Reserve notes in circulation.

The Act’s framers did not foresee that World War I would fatally wound the gold standard. The War got underway in Europe in June 1914, just before the Federal Reserve Banks began operations in November. European combatant nations soon suspended the gold standard in their own economies, and much gold flowed from Europe to find safe haven in the United States. These developments removed, for the time being, any binding gold constraint on money creation by the Fed. The Fed soon began creating money copiously to purchase Treasury securities and thereby help finance the U.S. government’s war mobilization. By the time the United States entered the war in April 1917, inflation in the United States (year-over-year change in the monthly Consumer Price Index) had already reached double digits. The inflation rate hit 20% by the end of the year. The Great War ended in November 1918, but U.S. inflation continued apace, peaking at a remarkable 23.7 percent rate in June 1920.

The wartime inflationary boom was followed by a sharp contraction, a deflationary recession, in 1920-21. According to NBER dating, the recession in real economic activity ran from January 1920 to July 1921. The month-over-month inflation rate turned negative in July 1920 and did not become positive again for two consecutive months until October-November 1922. The Fed had overseen a wartime inflation so great – unlike any under the pre-Fed classical gold standard – that the swing from inflation to deflation was unprecedented: From July 1919 to July 1920 the price index rose 23.7 percent, and over the following twelve months fell 15.8 percent.

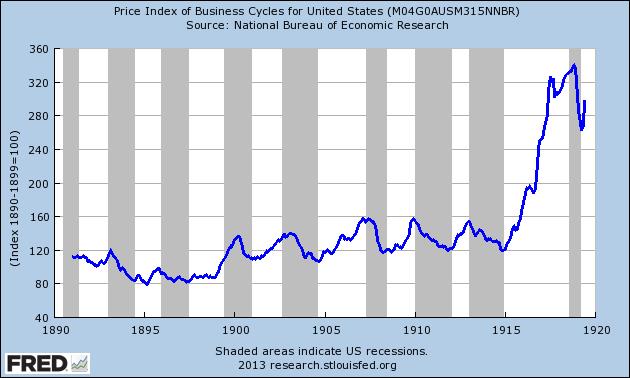

The standard CPI series does not go back before 1913, but the dramatic destabilization of the price level brought by the Federal Reserve Act plus the Great War can be seen in Figure 1, which charts the dollar price of a bundle of ten industrial and agricultural commodities.

Figure 1

The Fed’ second decade produced only moderate positive to mildly negative rates of inflation up to 1930, but then came a period of sharp deflation during 1930-33, reaching a 10 percent annual deflation in 1932. A recent study by Sandeep Mazumder and John H. Wood (Economic History Review, February 2013) views this as the final wringing out of the Fed’s WWI inflation. The period was also of course characterized by huge swings in real activity, from the boom of the Roaring Twenties to the depths of the Great Depression. Austrian critics have plausibly blamed the Fed for over-stoking the boom by holding interest rates too low before 1929, making a crash inevitable. In their celebrated Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz pointed out that the Fed, having nationalized the roles previously played by clearinghouse associations, particularly the lender-of-last-resort role, did less to mitigate the multiple banking panics of the early 1930s, with their sharply deflationary and depressive effects, than the clearinghouses had done in earlier panics like 1907 and 1893. They concluded with good reason that the economy would have suffered less if the Fed had not been created.

During the Second World War, the Fed was again drafted into providing inflationary finance. As Robert L. Hetzel and Ralph F. Leach have noted (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Winter 2001), “In April 1942, after the entry of the United States into World War II, the Fed publicly committed itself to maintaining an interest rate of 3/8 percent on Treasury bills,” which meant expanding credit as much as necessary. This time the inflation rate peak was 19.7 percent in April 1947. When the Fed sought to let the T-bill rate rise in 1947, “the Treasury adamantly insisted that the Fed continue to place a floor under the price of government debt by placing a ceiling on its yield.” Finally unshackled from this commitment by an “Accord” with the Treasury in 1951, the Fed from 1951 through 1964 kept inflation consistently low. But that didn’t last. In the mid-1960s, the Fed kicked off the peacetime Great Inflation by beginning to play the Phillips Curve, that is, trying to reduce unemployment by inflationary monetary expansion. Once job-seekers and employers stopped being fooled by inflation, the unemployment rate rose along with the inflation rate in the 1970s. (That “stagflation” episode could be profitably studied by those in the current Fed who seem to think that the inflation rate will not rise so long as unemployment and excess capacity measures remain high.) When financial market participants began driving up nominal interest rates to offset the shrinking purchasing power of the dollar, the Fed responded by trying to drive down interest rates with even easier money, which only threw more fuel on the fire. The inflation rate (CPI year-over-year) peaked at 14.8 in April 1980.

In the Great Moderation of 1985-2005, the Fed returned to lower inflation, and some commentators concluded that this time the Fed had finally learned how to manage a fiat money. Alas, again it didn’t last. The Fed had begun fueling an unsustainable housing boom by holding market interest rates too low for too long from 2001 to 2006 (at least as judged by the common diagnostic of the Taylor Rule). The consumer price index did not rise rapidly, but house prices (excluded from the CPI) did. We are still living with the fallout from the crash.

Since the crash the Fed has pursued an unconventional policy of near-zero nominal interest rates (negative rates in real terms) through the combination of “Quantitative Easing” and interest on reserves. Beginning in November of 2008, the massive bond purchase programs QE1 and QE2 have tripled the monetary base (the Fed’s own monetary liabilities), giving the banking system massive excess reserves. Yet money held by the public, measured by M1 or M2, has remained on a gradual growth path. The Fed deliberately neutralized the injection of reserves by paying banks interest to hold the excess reserves rather than lend them out and expand the broader money supply.

What was the point of the bond purchases, if not to expand the money supply? The point was credit allocation: in QE1 the Fed bought $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities to prop up the price of those securities. The Fed also allocated hundreds of billions in funds to lending programs directed at specific sectors of the financial industry. Credit allocation is not part of monetary policy, nor is it part of a lender of last resort policy, but it is instead a cronyism policy, benefitting some businesses at the general expense.

To conclude, let me summarize the findings of the 2012 Journal of Macroeconomics article by Selgin, Lastrapes, and White that O’Driscoll cited. Compared to the pre-Fed classical gold standard period,

1) The Federal Reserve’s management of monetary policy has dramatically increased secular inflation. Over the pre-Fed gold-standard period of 1879 to 1914 the compound annual inflation rate was -0.05%. A bundle of goods purchasable for $100 in 1879 was purchasable for $99.95 in 1914. Over the most recent 50 years, From September 1963 to September 2013, the compound annual inflation rate was 4.14%. A bundle going for $100 in 1963 cost $761.54 in 2013.

2) In addition to raising the average inflation rate, the Fed has also increased price level uncertainty, whether measured by a rolling standard deviation of the quarterly price level, or by the conditional variance of extrapolative price-level forecast errors at 10-year and longer horizons. The result of greater uncertainty about the future purchasing power of the dollar has been the near-disappearance of long-term corporate bonds and a corresponding discouragement to long-term investment planning.

3) The Fed has not tamed the business cycle. It has not reduced real output volatility as measured by percentage standard deviation from trend. Output volatility over the Fed’s entire 100 years has been much greater than in the pre-Fed period. Even if we discard the Great Depression, real output during the post-WWII period has been no calmer than the pre-Fed period, despite the U.S. economy having become more diversified and less subject to supply shocks.

4) The Fed has not reduced unemployment. We shouldn’t expect it to, of course, but this implies that its “maximum employment” mandate is absurd.