Within his essay, Gary Hufbauer shares a number of valuable insights into why some sanctioning efforts succeed and others fail. Hufbauer’s essay highlights, for example, that sanctioning efforts that receive broad international cooperation are only sometimes—but not always—more effective than unilaterally imposed sanctions. Similar to how sanctioning efforts’ success can be influenced by the degree of international cooperation a sanctioner receives, their success can also be influenced by how much support a sanctioned state obtains from other countries. Indeed, research from my forthcoming book Busted Sanctions: Explaining Why Economic Sanctions Fail suggests that sanctioning efforts will rarely succeed when sanctioned states are able to obtain significant levels of sanctions-busting support from other countries around the world. Third-party spoiler states can undercut the effectiveness of sanctioning efforts via both the trade and foreign aid they provide to sanctioned states.

Economic sanctions can profoundly affect their target’s economy and its commercial relationships with other states. Sanctions may disrupt trading relationships between firms in third-party and target states and can also harm the profitability of doing business with trade partners in target states. Economic sanctions can thus have far-reaching adverse effects on their targets’ trade with other countries. Yet there may also be third-party firms that can profit from exploiting the trade imbalances that sanctions create within target states and the lack of competition from rival firms in the sanctioning state(s). These firms will flock to the third-party states from which trading with target states is the most profitable. This can lead to the emergence of third-party spoiler states called trade-based sanctions busters, which dramatically increase their trade with target states after they have been sanctioned.

Having the support of trade-based sanctions busters can mitigate the adverse economic consequences that sanctions have on target states. While companies and consumers within target states must still pay a premium on the trade they conduct with firms in trade-based sanctions busters, concentrating their efforts to replace their lost trade within a small number of leading sanctions busters is more cost effective than trying to find new trade partners all over the world. Especially if such states have large markets that can absorb the target’s excess exports and can readily provide substitutes for sanctioned imports, the costs of adjusting to the sanctions may be fairly low. Additionally, the more profitable that a third-party state finds exploiting the sanctions imposed against a target state, the less likely it is to join in the sanctioning campaign.

Examining nearly a hundred cases of U.S. economic sanctions imposed from 1950-2002, I find that sanctioning efforts imposed against target states that have the support of trade-based sanctions busters are significantly less likely to succeed. My analysis relies on the data set collected by Hufbauer and his colleagues, but employs a new measure to identify trade-based sanctions busters. I find that if a sanctioned state receives the support of even a single trade-based sanctions buster in a given year, it can make U.S. economic sanctions 30% less likely to succeed in that year and increase the U.S. government’s likelihood of giving up on its sanctions by 7%. The efforts of just one active spoiler state can thus undermine the chances of economic sanctions succeeding.

Looking at the prolonged U.S. sanctioning efforts against both Cuba (1960–present) and Iran (1984–present), I find substantial evidence that both states have relied on the support of trade-based sanctions busters in holding out against U.S. sanctions. For decades, Iran relied on its close neighbor, the United Arab Emirates, to help it circumvent U.S.-imposed economic sanctions. Additionally, Iran leveraged significant sanctions busting support from China and a number of U.S. allies in Europe. In Cuba’s case, the Castro regime was able to leverage the commercial support of a large number of U.S. allies, including Japan, Great Britain, Spain, Canada, and France both during and after the Cold War’s conclusion. Interestingly, my research shows that the United States’ closest military allies are far more likely to become trade-based sanctions busters than other countries.

The leaders of sanctioned states can also use the foreign aid they receive from third parties to resist sanctioning efforts, but relying heavily on foreign assistance can also enhance leaders’ vulnerability to aid reductions. Leaders receiving surplus foreign aid flows in a given year may use them to help constituents that were adversely affected by sanctions and to reward loyal political supporters. This can help minimize the political pressure on leaders to concede to economic sanctions. At the same time, leaders who depend upon foreign aid also become vulnerable to the adverse effects of sudden aid reductions. Such reductions can place significant budgetary pressure on target governments already facing fiscal challenges due to sanctions. They can also exacerbate the already adverse economic conditions for the constituents of sanctioned states, cutting them off services and resources that the foreign aid had previously funded. Leaders experiencing aid reductions thus face far greater challenges in resisting sanctions. As such, sanctioning efforts imposed against states receiving foreign aid surpluses should be less effective, and sanctioning efforts imposed against states experiencing aid reductions should be more effective.

Third-party spoilers can play significant roles in influencing the foreign aid flows that sanctioned states receive. In the aforementioned U.S. sanctioning effort against Cuba, Fidel Castro was able to obtain substantial foreign aid packages from the Soviet Union during the Cold War and from Venezuela after Hugo Chávez was elected president. Indeed, Hufbauer and his colleagues have previously argued that so-called “black knight” spoilers can undermine the effectiveness of sanctioning efforts with the foreign assistance they provide to sanctioned states. Whereas previous efforts to find a link between black knight assistance and sanctions outcomes yielded inconsistent findings, my approach places the assistance that black knights provide within the broader context of the overarching aid flows that sanctioned states receive. I expect my approach can better capture the role that foreign aid plays in influencing the outcomes of sanctioning efforts.

To evaluate this argument, I examined the extent to which the success of sanctioning efforts was dependent upon changes in the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) that sanctioned states received in a given year. My analyses reveal that sanctions against states experiencing modest increases[1] in their foreign aid flows are approximately 9% less likely to succeed in a given year and 41% more likely to end in failure. Conversely, sanctions against states experiencing modest declines in their foreign aid flows are 9% more likely to succeed and 30% less likely to end in failure. These findings strongly support my argument and indicate that volatility in the foreign aid flows that sanctioned states receive dramatically influences sanctions’ prospects for success.

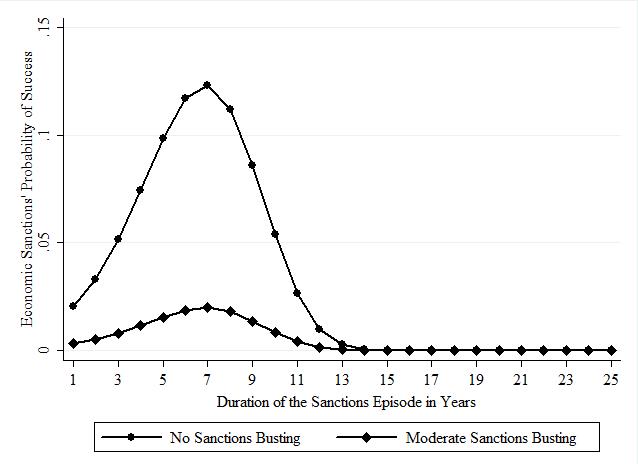

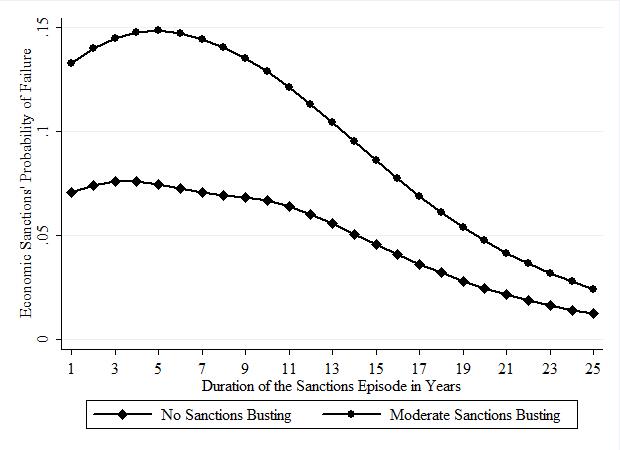

The impact of sanctions-busting aid and trade on the success of sanctioning efforts can best be illustrated graphically. The following figures illustrate two scenarios in which a typical state sanctioned by the United States receives no sanctions-busting support versus receiving a modest amount of sanctions-busting trade and aid. The figures show the impact of sanctions busting on the likelihoods of sanctioning efforts succeeding and failing over time.

Figure 1 focuses on the likelihoods of sanctions succeeding in a given year. As the figure shows, economic sanctions often take time to work. When a target state receives no sanctions-busting support, it is far more likely to capitulate to U.S. sanctioning efforts 4-10 years after they have been in place. In contrast, a state receiving a modest amount of sanctions-busting support is dramatically less likely to concede to U.S. sanctions. The marginal effects of sanctions busting on the success of sanctions diminish in the long-run, but primarily because long-running sanctions are unlikely ever to succeed.

Figure 1: How Sanctions Busting Influences Economic Sanctions’ Likelihoods of Success

Figure 2 illustrates the impact that sanctions-busting support has on the likelihood of the U.S. government terminating its sanctions without having achieved its objectives. As the figure shows, the U.S. government is much more likely to give up on sanctioning efforts in which target states receive a modest amount of sanctions-busting support. While these effects are strongest in the early years of sanctioning efforts, they still persist over the long term.

Figure 2: How Sanctions Busting Influences Economic Sanctions’ Likelihoods of Failure

In sum, my findings suggest that the external support that sanctioned states can leverage from third-party spoilers has a major and often decisive impact on the success of sanctioning efforts. Sanctioning efforts that have been busted by third-party spoilers are substantially less likely to be successful. U.S. policymakers may often be better off giving up on sanctioning efforts that have been busted as opposed to maintaining sanctions that will be costly to the U.S. economy and unlikely to succeed.

When giving up on sanctions is not an attractive option, policymakers can sometimes succeed in convincing and/or compelling trade-based sanctions busters to curb their trade with sanctioned states. In recent years, for example, the U.S. government has succeeded in obtaining the cooperation of the European Union and, at least in part, the United Arab Emirates in sanctioning Iran. Yet achieving such cooperation from trade-based sanctions busters tends to be both difficult and costly. Another strategy to make sanctioning efforts more successful is to convince international donors to cut off their aid to sanctioned states. This strategy raises some important humanitarian concerns, though, and runs counter to the broader “smart sanctions” movement that has sought to limit the adverse effects that sanctions have on countries’ general populations. In some cases, the tradeoffs involved in cutting recipients’ aid flows in order to help bring sanctioning efforts to a swift, successful resolution may be worth those costs. Overall, though, sanctioned states are far more advantaged in leveraging the support offered by third-party spoilers than even powerful sanctioners like the United States are in stopping it.

[1]A one standard deviation increase is employed, which translates into around a $230 million increase in foreign aid flows.