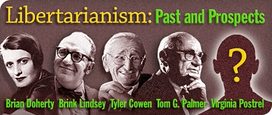

Brian Doherty asks: “Did this libertarian movement … actually accomplish anything of unquestionable significance?”

Yes: Bigger government.

But no, that isn’t as bad as it might sound to many Cato readers.

I see a few major policy achievements in a libertarian direction. In the United States inflation has come down from unacceptable levels in the 1970s to an eminently livable situation. Marginal tax rates have fallen from 70 percent to below 40 percent. There has not been a major cry to nationalize or otherwise cripple the hi-tech sector. Private capital markets have become more advanced, more liquid, and better able to fund new ideas. Of course on a global scale communism has fallen and many nations have reformed and improved their economies in a freer direction.

Libertarian ideas also have improved the quality of government. Few American politicians advocate central planning or an economy built around collective bargaining. Marxism has retreated in intellectual disgrace.

Those developments have brought us much greater wealth and much greater liberty, at least in the positive sense of greater life opportunities. They’ve also brought much bigger government. The more wealth we have, the more government we can afford. Furthermore, the better government operates, the more government people will demand. That is the fundamental paradox of libertarianism. Many initial victories bring later defeats.

I am not so worried about this paradox of libertarianism. Overall libertarians should embrace these developments. We should embrace a world with growing wealth, growing positive liberty, and yes, growing government. We don’t have to favor the growth in government per se, but we do need to recognize that sometimes it is a package deal.

The old formulas were “big government is bad” and “liberty is good,” but these are not exactly equal in their implications. The second motto — “liberty is good” — is the more important. And the older story of “big government crushes liberty” is being superseded by “advances in liberty bring bigger government.”

Libertarians aren’t used to reacting to that second story, because it goes against the “liberty vs. power” paradigm burned into our brains. That’s why libertarianism is in an intellectual crisis today. The major libertarian response to modernity is simply to wish that the package deal we face isn’t a package deal. But it is, and that is why libertarians are becoming intellectually less important compared to, say, the 1970s or 1980s. So much of libertarianism has become a series of complaints about voter ignorance, or against the motives of special interest groups. The complaints are largely true, but many of the battles are losing ones. No, we should not be extreme fatalists, but the welfare state is here to stay, whether we like it or not.

The bottom line is this: human beings have deeply rooted impulses to take newly acquired wealth and spend some of it on more government and especially on transfer payments. Let’s deal with that.

My vision for classical liberalism consists of a few points:

- A deep belief in human liberty, but seeing positive liberty (“what can I do with my life?”) as more important than negative liberty (“how many regulations are imposed on me?”).

- Accepting the package deal when it is indeed a package deal.

- Identifying key areas where we can strengthen current institutions and also strengthen liberty.

We need to recognize that some of the current threats to liberty are outside of the old categories. I worry about pandemics and natural disasters, as well as global warming and climate change more generally (it doesn’t have to be carbon-induced to be a problem). These developments are big threats to the liberty of many people in the world, although not necessarily Americans. The best answers to these problems don’t always lie on the old liberty/power spectrum in a simple way. Defining property rights in clean air, or in a regular climate, isn’t that easy and it probably cannot be done without significant state intervention of some kind or another.

Yes, I know some of you are climate skeptics. But if the chance of mainstream science being right is only 20% (and assuredly it is much higher than that), we still have, in expected value terms, a massive tort. We don’t let people play involuntary Russian roulette on others with a probability of 17% (one bullet, six chambers), so we do need to worry about man-made global warming.

Intellectual property in vaccines and drug patents also will become an increasingly critical issue on a global scale. The more human biomass there is in the world, the more humans will become a major target for viruses and diseases. No matter what our views, I don’t see any uniquely libertarian approach to the resulting questions of intellectual property. More and more economic value is being held in the form of intellectual property. The new libertarianism will have to be pragmatic at its heart.

Another major problem – the major problem in my view – is nuclear proliferation. What will the world look like when small and possibly non-traceable groups can afford their own nuclear weapons, or other weapons of mass destruction? The Cato Institute has pointed out many things America could do to become less of a target for terrorists. We could take in all this good advice and there would still be a big big problem.

In short, I would like to restructure classical liberalism, or libertarianism — whatever we call it — around these new and very serious threats to liberty. Let’s not fight the last battle or the last war. Let’s not obsess over all the interventions represented by the New Deal, even though I would agree that most of those policies were bad ideas.

If libertarians were to follow this course (and I don’t expect they will), the libertarian movement would become far more diffuse. It would run the risk of losing its intellectual and moral center. It would be less of a beacon. Many people fear such a development, and I can understand why. I don’t have any comforting means of outlining how a new liberty movement might look, how its slogans might sound, or what might prove to be organizing issues. We would run the risk of being too kooky and too mainstream at the same time.

In intellectual terms, we are cursed to live in interesting times.

These ruminations bring me back to Brian Doherty’s wonderful book. It is truly an amazing effort of intellect and of love. I can’t say enough good things about the book.

This will sound a little funny, but what I liked most about the book was how little I learned from it. (NB: most readers won’t have this same reaction, but I knew personally most of the people covered.) It felt like reading about me. On a few pages it was reading about me. The book got just about everything right.

The book hearkens back to those good old days when the nature of the fight, “liberty vs. power,” was really quite clear. America in the mid to late 1970s was a wreck, and libertarians indeed had a lot of the right answers.

Not all of those answers were adopted, but the new America is no longer a wreck. Where to go from here?

There is no simple answer to that question, but to understand the future we must confront our past. Doherty’s book is a very important and very thorough step in that dialog.

Read it, and ponder it, but don’t stop there.