In an ideal world, political discourse would consist only of logical arguments backed by empirical evidence. Visual persuasion would have no place.

There would be no fireworks on the Fourth of July; no pictures of the president speaking from the Oval Office or grinning at children or greeting soldiers or reaching over the sneeze guard at Chipotle; no “Morning in America” or “Daisy” commercials; no “Hope” or “We Can Do It” posters; no peace signs or Vs for victory or Black Power salutes; no news photos of gay newlyweds kissing or crowds celebrating atop a crumbling Berlin wall or naturalized citizens waving little flags; no shots of napalmed girls running in terror or the Twin Towers aflame; no Migrant Mother or dreamy Che Guevara; no political cartoons, Internet memes, or Guy Fawkes masks; no “shining city on a hill” or “bridge to the future”; no Liberty Leading the People or Guernica or Washington Crossing the Delaware; no Statue of Liberty.

In this deliberative utopia, politics would be entirely rational, with no place for emotion and the propagandistic pictures that carry it. And we would all be better off.

At least that’s what a lot of smart people imagine.

It’s an understandable belief. Persuasive images are dangerous. They can obscure the real ramifications of political actions. Their meanings are imprecise and subject to interpretation. They cannot establish cause and effect or outline a coherent policy. They leave out crucial facts and unseen consequences. They reduce real people to stereotypes and caricatures. They oversimplify complicated situations. They can fuel moral panics, hysteria, and hate. They can lead to rash decisions. Their visceral power threatens to override our reason.

Yet images are so ubiquitous they’ve been called “the lingua franca of politics.”

We can no more escape them than we can shed the human characteristics that make visual rhetoric effective. Whether conjured with words or presented in  pigments or pixels, images speak to our social, sensory, and emotional natures. Those aspects of human nature aren’t going to disappear just because intelligent, articulate people try to ignore or suppress them. Instead of dismissing, neglecting, or condemning the power of images, therefore, it makes sense to try to understand how they work and what different forms of visual persuasion might tell us about the relation between political audiences and those who seek to influence them.

pigments or pixels, images speak to our social, sensory, and emotional natures. Those aspects of human nature aren’t going to disappear just because intelligent, articulate people try to ignore or suppress them. Instead of dismissing, neglecting, or condemning the power of images, therefore, it makes sense to try to understand how they work and what different forms of visual persuasion might tell us about the relation between political audiences and those who seek to influence them.

Consider, to begin with, the limitations of the rational ideal. Reasoned political discourse is persuasive when it connects arguments to the audience’s pre-rational (which is not the same as irrational) commitments and desires, addressing the meanings through which we define our lives. People do not get argued into aspiring to be good parents, ingenious inventors, environmental stewards, creative artists, successful entrepreneurs, or faithful Christians. Debate does not make us see ourselves as compassionate, independent, courageous, or smart. It does not make us identify as female or black or Jewish or the children of immigrants. It does not make us long for prosperity, freedom, equality, or security. Such values and identities emerge from temperament and experience, psychology and culture. Rational deliberation can neither establish nor abolish them. It can only explain why certain actions would express or further those values and identities, or why alternative policies would undermine them.

Imagery, by contrast, reaches the emotional centers of the brain before it registers cognitively (assuming it ever does). By moving our emotions and giving form to our hopes and fears, visual rhetoric thus has the potential to influence how we imagine ourselves.

It offers what Grant McCracken, in a discussion of commercial advertising, calls “symbolic resources, new ideas and better concrete versions of old ideas” through which we come to define ourselves and our social groups. Political imagery can turn issues into themes, establishing an emotional bridge between our evolving identities and specific actions, such as voting for a particular candidate or supporting a particular law. It can also heighten the salience of some concerns—crime, say, or women’s rights or environmental protection—so that we decide our political allegiances according to those, rather than competing, less effectively represented issues.

Visual persuasion, however, is not a single phenomenon. It comes in different species, with different political implications. Take the Fourth of July fireworks striking wonder in the oohing and aahing crowds. Viewing fireworks is a shared communal experience that unites spectators in patriotic celebration. Everyone watching participates and knows everyone else is doing so at the same time. Fireworks are also a kind of gift, a non-excludable public good open to anyone who can see the sky. Their grandeur is overwhelming, and its creation requires wealth and technological mastery. Like the precision flying of the Blue Angels, fireworks wed aesthetics and power. They are an awe-inspiring spectacle, belonging to the sublime.

Like the precision flying of the Blue Angels, fireworks wed aesthetics and power. They are an awe-inspiring spectacle, belonging to the sublime.

As political persuasion, fireworks are a liberal remnant of the pageantry and magnificence used by authoritarian rulers to inspire popular loyalty. Think of Elizabeth I’s annual progresses, the coronation of Napoleon, or Moscow’s recently revived May Day parades. You give the public a show that simultaneously provides aesthetic pleasure, makes people feel part of something bigger, and reminds them that you can wield some pretty impressive force. Even in its darkest forms, such as Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies, magnificence aims primarily at winning and reinforcing followers’ uncoerced allegiance. While the spectacle may be intimidating to outsiders, within the group it engenders pride, devotion, loyalty, and love. Fear is mostly a side effect.

Other types of political spectacle do, however, seek to instill terror as a means of enforcing compliance. Consider public executions and the display of executed corpses, whether as government policy or the work of nonstate actors with political goals, such as jihadi groups or the Ku Klux Klan. In its heyday, the KKK was an effective terrorist organization in large measure because it combined visually striking spectacle with the credible threat of violence. A burning cross warned of brutality to come, intimidating both its immediate target and a broader public.

Whether pleasurable or terrifying, political spectacle assumes that the audience’s primary decision is whether to identify with the regime and conform to its rules.  Ancient and hierarchical, spectacle elicits only the most general forms of consent and appeals to the most universal motivations and emotions. Modern species of visual persuasion, born from new types of media and new theories of politics, are more granular and egalitarian. They address more specific audiences, evoke a wider range of emotions, assume greater equality between audience and influencer, and shape perceptions of particular individuals, policies, or ideas. Rather than inspiring or coercing political unity, they often fuel factionalism and dissent.

Ancient and hierarchical, spectacle elicits only the most general forms of consent and appeals to the most universal motivations and emotions. Modern species of visual persuasion, born from new types of media and new theories of politics, are more granular and egalitarian. They address more specific audiences, evoke a wider range of emotions, assume greater equality between audience and influencer, and shape perceptions of particular individuals, policies, or ideas. Rather than inspiring or coercing political unity, they often fuel factionalism and dissent.

Take satirical illustrations, one of the earliest and most enduring products of printing. From Reformation woodcuts portraying the pope as Antichrist to the latest caricatures of Barack Obama or Tea Party sympathizers, this form of visual rhetoric ridicules, ostracizes, mocks, and sometimes dehumanizes the opposition. Even at its gentlest, it intensifies divisions, if only by flattering those who share the creator’s political commitments and sense of the absurd. Satirical cartoons persuade not by changing minds but by reinforcing existing commitments and identities. They rally the troops. Those who disagree find them unconvincing, unfunny, and unfair—added proof that their opponents are just as bad as expected. Visual satire works because creator and audience share common attitudes and beliefs.

Satirical cartoons persuade not by changing minds but by reinforcing existing commitments and identities. They rally the troops. Those who disagree find them unconvincing, unfunny, and unfair—added proof that their opponents are just as bad as expected. Visual satire works because creator and audience share common attitudes and beliefs.

In all its modern forms, visual persuasion requires more than artistry. It demands an understanding of the audience. When Life magazine debuted with Margaret Bourke-White’s photo of Fort Peck Dam on its cover, the editors could assume that readers would see a thrilling example of progress, not a waste of taxpayer money, an environmental crime, or a boring bunch of cement. The Farm Services Administration photographers documenting poverty in the Great Depression anticipated that their audience would view subjects like Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother with sympathy rather than contempt and would believe that their plight could be eased by New Deal policies. When White House photographer Pete Souza recently tweeted his shot of Obama pointing over the sneeze guard, he presumably expected the audience to perceive a man of the people doing a charmingly normal thing, not an imperious chief executive breaking the rules. Oops.

The great mistake we make when considering political imagery, especially photography, is to assume visuals simply reflect is—a mechanically accurate representation of the world—when they in fact embody ought—an emotional sense of how things should or shouldn’t be. “All picturing is rhetoric,” declares advertising scholar Linda Scott. She’s right. Even an unaltered, mechanically objective photograph represents a bounded and flattened version of reality. Every image is selective. It requires context and judgment to interpret, and that interpretation is infused with emotion and cultural meaning.

The match between audience and image is especially critical for one of the most influential yet least examined forms of visual political rhetoric: glamour. In current everyday usage, the term glamour has become nearly synonymous with fashion, losing even its long-established connections with travel, cinema, and interior design. But we need only think of the terms glamorous and glamorize to realize that glamour is about much more than clothes.

Glamour is a form of communication that, like humor, arouses a distinctive emotion in the audience and takes many different forms, depending on personality and cultural context. While humor generates amusement, glamour produces a pang of projection and longing. When we find something glamorous, we get the feeling of “if only”: If only I could wear those clothes, belong to that group, drive that car, win that prize, have that job, be (or be with) that person, if only life could be like that.  Glamour translates inchoate desires—for love, wealth, power, beauty, sex appeal, adulation, respect, friendship, fame, adventure, freedom, or significance—into specific images and ideas, offering a lucid glimpse of desire fulfilled. It makes us feel that the life we dream of is possible, and to want it even more.

Glamour translates inchoate desires—for love, wealth, power, beauty, sex appeal, adulation, respect, friendship, fame, adventure, freedom, or significance—into specific images and ideas, offering a lucid glimpse of desire fulfilled. It makes us feel that the life we dream of is possible, and to want it even more.

In the early years of the civil rights movement, the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier excoriated Ebony for creating a glamorous “world of make-believe” with its profiles of wealthy, famous, influential, and highly atypical black figures. Frazier was correct that the journalism was selective, but he was wrong about how glamour works. He assumed it would encourage complacency, when in fact it fuels discontent. Glamour intensifies longings by giving them specific form. Ebony proved a potent political instrument.

With its promise of a different, better life in different, better circumstances, glamour is as useful in political persuasion as it is in commercial advertising. It is all about hope and change.  Although we commonly associate political glamour with public figures, notably John F. Kennedy, as visual persuasion it is better suited to policies and ideas than to politicians. Glamour requires mystery, which the intense scrutiny and populist expectations of contemporary campaigns tend to destroy. (Obama’s 2008 glamour was an exception.) A not-yet-adopted policy or a utopian ideal shimmers alluringly in the distance, its difficulties and costs concealed.

Although we commonly associate political glamour with public figures, notably John F. Kennedy, as visual persuasion it is better suited to policies and ideas than to politicians. Glamour requires mystery, which the intense scrutiny and populist expectations of contemporary campaigns tend to destroy. (Obama’s 2008 glamour was an exception.) A not-yet-adopted policy or a utopian ideal shimmers alluringly in the distance, its difficulties and costs concealed.

In the 20th century, glamour sold the idealized garden cities and limited-access highways that established a new norm of urban planning and suburban living. Its visual rhetoric made the technological future of spaceflight and miracle fibers alluring and taught the “modern woman” she could combine liberation and love. Glamour encouraged working-class aspirations. “When we went to the cinema and [saw] people switching lights on and opening fridges and hoovering, it was a different world,” a British woman recalled decades later. “I think it made us all a bit more ambitious.”

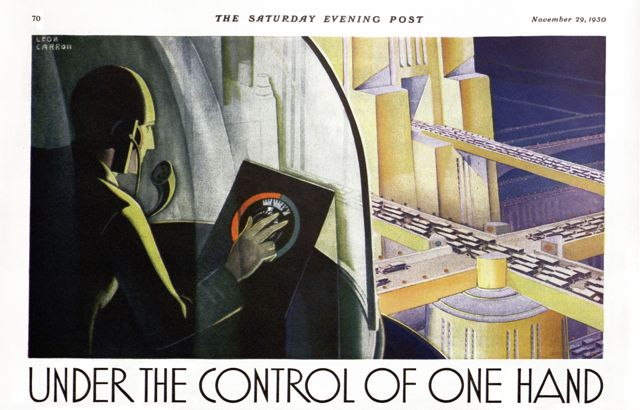

Glamorous political and commercial imagery—and their awkward but compelling coexistence in World’s Fair exhibits, such as General Motors’ famous 1939 Futurama—promoted the ideal of rational planning. “A perfectly ordered mechanical civilization” promised escape from the unpredictable, stressful, and seemingly haphazard developments that made modernity so unnerving.  “Under the Control of One Hand” might have been an ad slogan pitching radios, but the idea and the illustration that expressed it were political.

“Under the Control of One Hand” might have been an ad slogan pitching radios, but the idea and the illustration that expressed it were political.

Such images worked because they channeled deep longings while disguising difficulties and flaws. Glamour is an illusion—the word originally meant a literal magic spell that made people see things that weren’t there—but that illusion tells the truth about desire. That combination makes glamour extremely aggravating for people who don’t share the same persuasive goals, whether they’re feminists condemning fashion ads, taxpayer groups fighting California’s high-speed rail, or E. Franklin Frazier demanding that the black bourgeoisie admit its “inferiority and inconsequence in American society.” How can anyone fall for this nonsense? It’s a scam, a trick, a delusion! It’s a lie!

Facing the persuasive power of glamour, political opponents have several possible strategies. They can try to argue with the underlying longings, as countless critics have tried to convince women not to care about being beautiful. And, like those countless critics, they will fail. People do not get argued into who they want to be.

Alternatively, opponents can try to puncture the illusion, revealing the flaws and difficulties hidden in the artificial grace.

Glamour is in fact fragile; experience more often than not will break the spell. (Obama’s glamour faded once he had to govern.) Political opponents just don’t want to wait for experience to take its course. They’re usually trying to head it off. So they need a contrary picture: realistic, horrific, or ridiculous. They can try to fill in the hidden details with the banal if unpleasant truth. They can suggest that glamour is hiding something truly awful. Or they can make the illusion look silly. With a tendency to backfire, horror is the most dangerous of these approaches; humor the most effective but difficult to pull off.

There is one other possibility. They can create their own version of glamour.

Confronting the allure of planning, in 1949 F.A. Hayek observed that “socialist thought owes its appeal to the young largely to its visionary character; the very courage to indulge in Utopian thought is in this respect a source of strength to the socialists which traditional liberalism sadly lacks.” Hayek’s popular 1944 book The Road to Serfdom countered the glamorous vision of planning with a combination of reality—here’s what would be required to get that to work—and horror (hence the title). But it did nothing to make free markets glamorous.

That task was accomplished in 1957, by an author who’d trained her visual imagination absorbing the movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Ayn Rand called her novels “romantic,” because they portrayed the world not as it was but as she believed it ought to be. Her works channeled her longings into characters, settings, and descriptions that made the ideal seem possible. It’s no accident that of all the 20th century’s proponents of libertarian ideas, she was the one who moved the most hearts and infuriated the most critics. She created glamorous pictures with words. She mastered visual persuasion.

Image courtesy of the California High-Speed Rail Authority.