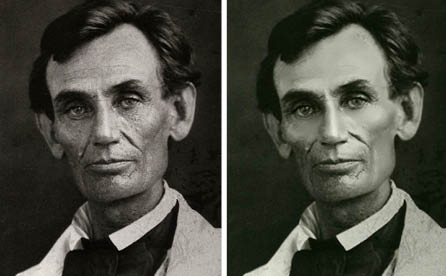

You’ve heard the one about how Washington is Hollywood for ugly people, right? You may have also heard the less quippy but oft-repeated claim that were Abraham Lincoln to run for president today, he’d never be elected—too gangly, too hollow-cheeked, too…ugly. A variant on this latter assertion is a pointed retelling of the first televised presidential debate, in 1960: People who listened on the radio thought that Richard Nixon had bested his opponent, but those who watched it on television found John F. Kennedy to be the winner. The difference, of course, is supposed to have lain in Kennedy’s good looks, spotlighted even more than usual by an illness that left Nixon appearing gaunt and sickly the night of the debate.

At first blush, these narratives seem to contradict the Hollywood-for-ugly-people maxim about politics. A closer look at whom we consider beautiful—and why we consider them such—shows that these two claims about the relationship between physical appeal and politics are less opposed than they appear.

When asked to describe an attractive person, many of us might conjure up an image of someone who looks extraordinary: the ethereal beauty of, say, Elizabeth Taylor, or the rugged yet sculpted features of George Clooney. Yet the more we learn about what the human eye finds appealing, the more we learn that what we find good-looking is not what is unique, but what is average. Case in point: Computer-generated composite faces are consistently rated as more alluring than actual, singular human faces. And faces that are considered highly attractive usually feature nothing more striking than average features that are just a shade exaggerated—lips a bit fuller, eyes a bit larger—as opposed to a truly unique feature like Taylor’s famed violet eyes. Even one of the most frequently quoted studies on beauty, about how babies’ eyes will linger longer on faces considered beautiful by adults, can be construed as an endorsement of the mean: In another study, babies focused longer on a series of dots and lines that resembled a face than they did on a formless arrangement of figures. One conclusion: Babies might like “beautiful” faces because they’re more facelike than the average face, not because of their straight-up aesthetic appeal.

As it happens, there’s a profession in which an exaggerated averageness lends a particular advantage. Candidates for public office climb over themselves to pose for photographs at local dining spots and bowling alleys, dandling babies all the while, in an effort to project an “everyman” (or, less often, everywoman) image. As Virginia Postrel reminded us, even Barack Obama recently made “news” by reaching over the sneeze guard at Chipotle, in a perhaps failed attempt to be average. Politicians stake their claim on averageness, and what better way of seeming average than to seem, if not beautiful, pretty? To be pleasantly pretty (or pleasantly nice-looking if the term pretty seems too feminine for the 78% to 92% of public office holders who are men) is to appear inherently average. You don’t even need to eat cinnamon buns at the local diner to do so.

I don’t want to suggest that we play “Hot or Not” with our elected officials—after all, they (ostensibly) didn’t sign up to have their looks evaluated along with their platforms. But in a leisurely stroll through the official websites of random state representatives, a certain kind of face makes a strong showing: one that resides in the liminal space between strict averageness and what we’d conceive of as beauty. Attractive enough, but attractive in a way that doesn’t call attention to itself. Washington might indeed be Hollywood for ugly people, if by “ugly” we mean the contrast between people whose job it is to entertain the crowd and those whose job it is to represent it. But to be actually ugly—as opposed to the pleasant faces that we see in news clips of the week’s political vaudeville—is to simply be the flipside of the extraordinary beauty of the Taylor-Clooney sort. That is, ugliness is remarkable, in contrast to the simple unremarkability of being nice-looking, à la any sampling of the House of Representatives. Those who fall too far outside the margins, whether it be the “Breck girl” narrative surrounding John Edwards, or someone with the face of Lincoln, can be more easily dismissed. It’s the median voter theorem, without all that policy mucking it up: Stick to the middle ground and you’ll come out ahead. And if that middle ground wears an attractive guise, all the better.

As Virginia Postrel argues on her essay on visual persuasion and the state, we rely upon the glamour of iconography to give form to our deepest desires; in turn, savvy strategists use that glamour as a form of persuasion. But beauty has always been a gentler form of manipulation than glamour. It seduces us not with a promise but with a blessing: Where glamour can be cruel, we only consider beauty cruel when it has left us, or once it’s tiptoed into the realm of glamour via iconography. Tolstoy wrote, “It is amazing how complete is the delusion that beauty is goodness”—indeed, that delusion extends to people’s tendency to endow good-looking folks with the “halo effect” of beauty, including politicians, assuming them to be more sympathetic than those whose looks are irregular.

When we consider the averageness inherent in everyday, run-of-the-mill beauty, it speaks not as much to delusion as it does to hope. If, as Tolstoy claimed, we associate beauty with goodness, our minds identify beauty in the pedestrian because of our longing to see goodness in the everyday—quite a contrast to the cynicism that currently marks much of the public relationship to statecraft.

Our gift at finding beauty in the ordinary speaks to the most plaintive of civic hopes: That those we democratically elect to be our representatives are exactly that—representatives, not leaders or officials or any of the other various words with which we christen the chosen. It’s easy to moan about the celebrity culture that gave birth to magazine features that showcase movie stars clutching grande lattés while grocery shopping, but underneath such fluff lies a simple wish to see ourselves represented publically. Politicians: They’re just like us. Beauty is often construed as something for the elite—something out of reach for the hoi polloi, as opposed to, well, “the beautiful people.” To believe that is to partly misconstrue beauty. In truth, beauty is populist to its core.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.