As the editor of Reason, I used to be infuriated at the way the Los Angeles Times and other mainstream publications consistently capitalized Libertarian when referring to the magazine or its parent organization, the Reason Foundation. They wouldn’t capitalize liberal or conservative, republican or democrat, unless they were referring to a political party. (Most Republicans are, after all, democrats, and I’ve never met a Democrat who wasn’t a republican.) Why couldn’t they understand that Reason was not a party organ but, like its liberal and conservative counterparts, a magazine of ideas? Were the copy editors just stupid?

After a decade of hearing me gripe, my husband cracked the code: Maybe newspapers don’t think of Libertarian as a party label like Democratic or Republican, he suggested. Maybe they think of it as a religious description, like Catholic or Presbyterian.

Great.

The problem is, I knew he was right. To an outsider, official libertarianism, represented most prominently by the Cato Institute, the Libertarian Party, and a zillion website comments posts, does indeed look like a doctrinaire sect with a well-rehearsed catechism. The movement even has a proselytizing tract, the World’s Smallest Political Quiz. Everything flows from a single principle: self-ownership or non-aggression. It’s political philosophy as simple algebra.

Insiders know it’s more complicated, of course. But so is the Catholic Church, and even religious fundamentalists have their quarrels. (Bob Jones thinks Billy Graham is a dangerous liberal.)There’s no libertarian hierarchy to excommunicate heretics, but within libertarian organizations free thinkers do feel informal pressures to conform. It’s safest and most rewarding to stick to a straightforward anti-government script, especially since the government can be counted on to provide plenty of provocation. Nobody comes to libertarians to get complex analyses of tradeoffs or institutions. On TV or op-ed pages, you know what the libertarian representative will say before he or she says it. Donors don’t get excited by subtle arguments or policy details. The libertarianism the public hears is thus very simple: government bad, freedom good.

As a result, some of the most important ideas and intellects of the—what shall we call it?—nameless liberalism that descends from the Scottish Enlightenment don’t qualify as “libertarian.” They don’t adhere to the deductive reasoning promoted by Ayn Rand or Murray Rothbard. They aren’t “principled” or “hard core.” In a 1997 Reason interview, the great economist Ronald Coase disqualified himself:

My views have always been driven by factual investigations. I’ve never started off—this is perhaps why I’m not a libertarian—with the idea that a human being has certain rights. I ask, “What are the rights which produce certain results?” I’m thinking in terms of production, the lives of people, standard of living, and so on. It has always been a factual business with me….I don’t reject any policy without considering what its results are. If someone says there’s going to be regulation, I don’t say that regulation will be bad. Let’s see. What we discover is that most regulation does produce, or has produced in recent times, a worse result. But I wouldn’t like to say that all regulation would have this effect because one can think of circumstances in which it doesn’t.

Libertarianism, in this view, is incompatible with empiricism or consequentialism. I don’t believe that, but a lot of people do. Neither Friedrich Hayek nor Milton Friedman would have passed philosophical muster as a Libertarian Party candidate. (A negative income tax? Taxation is theft. School vouchers? Ditto. And let’s not get started on bilateral trade agreements or fiat money.) Yet any definition of libertarian that excludes Friedman or Hayek is useless.

Rather than defining “libertarian” by appealing to deductive logic and so-called first principles, we can better understand the American libertarian movement as a sometimes uneasy amalgam of four distinctive yet complementary traditions, two cultural and two intellectual.

Culturally, the “leave us alone coalition” encompasses two different traditions, outlined by historian David Hackett Fischer in his mammoth 2004 book Liberty and Freedom. (Fischer is an anti-libertarian “vital center” liberal in the Arthur Schlesinger Jr. mode, and these are not the only traditions he limns.) The first and more politically prominent is the get-out-of-my-face-and-off-my-land attitude Fischer calls “natural liberty,” a visceral, sometimes violent defense of self and clan. Think “Don’t Tread on Me” and gun rights. The second is the live-and-let-live ideal expressed by the biblical prophecy “they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree; and none shall make them afraid.” Think “Follow Your Bliss” and gay marriage.

Natural liberty is the heritage of the American South, particularly the piedmont and mountains settled by Scots-Irish immigrants. It is ornery. Fig-tree pluralism is Midwestern, brought by German refugees. It is nice. Despite their contrasting temperaments, both traditions place a high value on independence, which implies personal responsibility as well as freedom, and personal space. Both foster a hands-on pragmatism that can promote entrepreneurship and inventiveness. Mix the two and you get Ronald Reagan’s California, the land of property-tax rebellions and New Age seekers. These two traditions make American libertarianism distinctively American.

Culture, not philosophy, largely accounts for the colorful characters celebrated in Brian Doherty’s book (or books—these traditions are also the heritage of Burning Man). And culture, not philosophy, is more often than not what motivates grassroots activists. Cultural libertarianism says This is wrong before figuring out exactly why. Although often expressed in absolutist rules, the better to guard against government encroachment, cultural libertarianism is, by its nature, empirical and consequentialist. It’s animated by a vision of personal freedom and worried about what happens in the real world. It can also be entrepreneurial and creative, the source of such radical innovations as home schooling and the personal computer.

Cultural libertarianism can only survive ideological challenge, however, if it develops intellectual underpinnings. The 20th century proved that much. Against arguments for the fairness and efficiency of central planning, “I don’t like it” struck most people as impossibly old-fashioned. Why not make everyone better off? What’s the harm of a little more regulation? The cultural argument misses the indirect threats to people who aren’t in view, the unseen versus the seen effects of bad policy.

The answers were supplied by two seemingly incompatible intellectual traditions. The more visible offered a libertarian version of the Continental quest for certainty. It was supremely modern—as rational and precise as a skyscraper, as ahistorical as Le Corbusier’s plans to remake Paris. Here are the answers, promised the schools of Rand and Rothbard. Everything you need to know follows from the nature of man and the definition of freedom. A libertarian society is not relative but absolute. You either have one or you don’t. There is no compromise between food and poison (news to toxicologists). We are working for utopia.

Like the modernist ideologies it opposed, this deductive libertarianism could be inspiring, especially in the pages of a novel. It was comfortingly absolute. It promised a world made new and better, a future worth striving for. It had glamour. But how could a deductive libertarian work for a better future, if “better” implies accepting incremental change? Short of privately financed space colonies, libertarians weren’t going to get a chance to build a new society from scratch. (I’m not so sure about those space colonies either. No human culture starts from scratch.)

For decades, the deductive tradition has defined libertarian identity and dogma, while the empiricist tradition has achieved libertarian goals. For parallelism, we can call this second intellectual strand the Hayek-Friedman tradition, though that unnecessarily truncates the list of Nobel laureates it has produced. (It also understates the cultural libertarianism of Friedman’s popular works and the Continental influences on Hayek’s thought.) Libertarianism need not be formulaic. There has long been a lively, open-ended libertarianism for inquiring minds, whether curious about the results of trucking deregulation, the consequences of Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the incentives that shape bureaucratic action, the neurological basis of interpersonal trust, the causes of the Islamic world’s economic decline, or the predictive potential of idea futures markets. Not all this work has been empirical. The tradition has produced great theorists, including Hayek, Coase, James Buchanan, Armen Alchian, and Richard Epstein, to name just a few. But their theories are informed, tested, and revised by empirical observation, just as Adam Smith’s were. Most of the libertarian movement’s persuasive and policy triumphs have come from this non-utopian, empiricist approach.

Instead of the Continental quest for certainty, this second intellectual tradition is inspired by the Anglo-Scottish heritage of skeptical inquiry. It is the tradition of Smith and Hume, animated by a love not only of liberty but of the learning, prosperity, and cosmopolitan sociability made possible by a society in which ideas and goods can be freely exchanged. It looks for understanding, for facts, and for solutions to specific problems. Its distrust of grand plans and refusal to embrace the one best way—even the one best libertarian way—made it out of place in the 20th century. They make it essential for the 21st.

In the 20th century, the greatest philosophical challenges to classical liberalism came from its socialist offshoots, with their claims of fairness and efficiency. As I’ve discussed at length in The Future and Its Enemies and more concisely in my 1999 Mont Pelerin Society speech, those are no longer the primary threats. Markets have demonstrated that they can deliver the goods, even to the poor. Calling for a small increase in the minimum wage or the earned income tax credit is very different from nationalizing industry, imposing wage and price controls, or enacting confiscatory tax rates.

Now I worry that libertarians will fight the old battles with the old allies and lose a new war—possibly a literal one. To quote the Mont Pelerin address:

The most potent challenge to markets today, and to liberal ideals more generally, is not about fairness. It is about stability and control—not as choices in our lives as individuals, but as a policy for society as a whole. It is the argument that markets are disruptive and chaotic, that they make the future unpredictable, and that they serve too many diverse values rather than “one best way.” The most important challenge to markets today is not the ideology of socialism but the ideology of stasis, the notion that the good society is one of stability, predictability, and control. The role of the state, in this view, therefore, is not so much to reallocate wealth as it is to curb, direct, or end unpredictable market evolution.

Stasis alliances have solidified over the past eight years. Today no one thinks it a bit unusual to find “progressives” arrayed with “conservatives” to oppose international trade, biomedical technologies, or the general idea of consumer choice.

And since 9/11, we have all become hyperaware of the Islamist quest for certainty, purity, and absolute stasis—a 21st-century version of utopian absolutism, promulgated largely by a nimble, decentralized non-governmental organization. Not only have ideologies shifted, but so have institutions. While the last century’s greatest threats to liberty, prosperity, and peace came from totalitarian nation-states, today’s come from transnational organizations—ranging from imperialistic regulators (the European Union) to violent religious crusaders—and from “failed states” where warring gangs have superseded governments. Focusing on the nation-state as the source of all threats to liberty is anachronistic. Oddly enough, promoting liberty may in some cases require libertarians to work at state-building, or at least state-reforming. I don’t know that he would agree with the characterization, but that is how Tom Palmer spends much of his time, spreading libertarian ideas in countries with little to no experience of liberal institutions.

Against these ideological and institutional challenges, liberal society will need the practical lessons of libertarian scholarship on decentralized order and knowledge sharing. It will need the cultural libertarianism that knows liberal society is not just familiar but good. And it will need the 18th-century wisdom that lets skepticism happily coexist with civility and reason. Surviving the 21st century with our sanity and civilization intact will require less Nietzsche and more Hume.

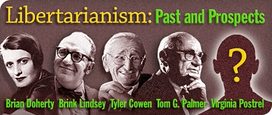

At a more mundane level, countering the arguments for stasis requires a vigorous defense and deepened understanding of open, dynamic, learning societies—not only from libertarians but from new allies. Brink Lindsey’s call for a liberal-libertarian coalition may sound crazy when you look at the Democratic Congress, the 2008 presidential field, or the Democrats’ reflexive demonization of pharmaceutical companies. But if you want to defend cosmopolitan individualism, including commercial freedom, creating such an alliance could prove essential.

The trick is to find genuinely shared values. A political movement, as opposed to a tactical alliance, must be united by more than agreement on a single issue (“I’m against farm subsidies. You’re against farm subsidies. Let’s get together.”) Frank Meyer’s fusionists shared the conviction that expansive government threatened both liberty and virtue and that those ideals were intertwined. The values that could similarly unite (some) liberals and (some) libertarians are those that most irritate stasists of all stripes: self-definition, knowledge and discovery, free exchange across national or tribal boundaries, the ability to take personal risks and the responsibility to bear the consequences, the pursuit of happiness. We know we’re liberals. The question is, Are they?