I believe a critical point has been lost in the responses to my lead essay. My concern in my essay and my books is a simple and regrettable fact: the epidemics worldwide of obesity and diabetes that occur whenever populations pass through a nutrition transition from a traditional diet and lifestyle, whatever that may be, to a western one. Something is causing that, and because obesity and diabetes, particularly type 2, are intimately linked to insulin resistance, we should be looking ultimately and desperately for the cause of insulin resistance. Geneticists would say we’re looking for the environmental trigger that reliably and often dramatically increases the prevalence of the obese and diabetic phenotype, regardless of the underlying human genotype. And because insulin resistance, obesity, and diabetes are all intimately linked to heart disease, that trigger is almost assuredly going to be a cause of coronary heart disease as well.

But in this country, nutrition and chronic disease research from the 1950s onward was obsessively focused on a very different question: the dietary cause of heart disease in the United States and Europe. When the researchers decided on the basis of exceedingly premature evidence that dietary fat was the culprit, that drove all public health debates and thinking ever after. Even hypotheses about the cause of obesity and diabetes had to be reconcilable with the belief that saturated fat caused heart disease. As such, the evidence implicating insulin resistance in the disorder (and so the carbohydrate content of the diet) was delayed by 30 years in its acceptance, as I discussed in Good Calories, Bad Calories. Its implications are still not accepted because they clash with what remains of the dogmatic belief that saturated fat causes heart disease. And this all happened because researchers were asking the wrong question (and they got the wrong answer even to that): “why CHD in America now,” rather than “why obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance in populations worldwide whenever they westernize?”

Sugar and refined grains seemed to be the most likely answer to the right question, but this was swept under the rug or pronounced quackish because that answer also didn’t square with the saturated fat hypothesis. The key to all good science is understanding the question you’re asking and how it relates to the answers you need to find. And this problem is manifested once again in the responses of Drs. Guyenet and Freedhoff.

Now that we’re almost literally neck deep in obesity and diabetes, the right question is vitally important to answer. If the sugar hypothesis is wrong, it is critically important that it be refuted definitively. That can only happen on the strength of far, far stronger evidence than Dr. Guyenet provides in his somewhat flip and casual response. And if the sugar hypothesis is unambiguously refuted, whatever hypothesis steps up as the next prime suspect has to be very carefully considered. (i.e., not the simplistic notion that people eat too much and move too little). We need a hypothesis that holds the promise of explaining the epidemics everywhere.

In stopping an epidemic, nothing is more important than correctly identifying its cause. Where we are today with obesity and diabetes reminds me of where infectious disease specialists were through most of the 19th century, when they blamed malaria and other insect-born diseases on miasma, or the bad air that came out of swamps. That was mildly effective, in that it was an explanation for why the rich in any particular town preferred to build their homes on hills, high above the miasma and, incidentally, away from the swamps and lowlands and slums where the vectors of these diseases were breeding. But only by identifying the vectors and the actual disease agents do we help everyone avoid them and eradicate the diseases. Only by unambiguously identifying the cause can we effectively design treatments to cure it. The kinds of explanations that Dr. Guyenet and Freedhoff put forth – highly palatable foods or ultra-processed foods – are the nutritional equivalents of the miasma explanation. They sound good; they might help some people incidentally eat the correct diets or offer a description of why other people already do, but they’re not the proximate cause of these epidemics. And there is a proximate cause. We have to find it. I can guarantee it’s not saturated fat, regardless of the effect of that nutrient on heart disease risk. What is it?

Now I am going to focus primarily on Dr. Guyenet’s response, as his was by far the most antagonistic, questioning both the history I present in the lead essay as well as the conclusions I’ve derived from the history and the science. While Dr. Guyenet does indeed challenge “specific and testable assertions” related to my lead essay, the one assertion he does manage to refute successfully is not, regrettably, an assertion I made in the article. As for the rest, the evidence against is not nearly as compelling as he presents it.

First, Dr. Guyenet examined “the 1980 Dietary Guidelines to determine if they condemn fat and take a weak stance on sugar as suggested.” He then set out to determine whether the 1980 Guidelines contributed to obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. He concluded that they didn’t.

I was under the impression when I wrote the essay, though, and still am upon re-reading it, that I do not make such a simplistic assertion. The point that I made is not about the 1980 USDA Guidelines alone – Dr. Guyenet and I both note that they urged readers to avoid too much sugar – but rather the entire movement of the research community to demonize fat, and the journalistic coverage of it, and the series of government documents, and the consensus conferences that followed along because of it—all part of the same concerted public health effort that led us by the late 1980s to believe that the essence of a healthy diet is its relative absence of fat and saturated fat. As an unintended consequence, this ill-conceived dogma-building directed attention away from the possibility that sugar has deleterious effects independent of its calories.

These government reports, as I noted, included the FDA GRAS report on sugar in 1986, the Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health in 1988, the National Academy of Sciences Diet and Health report in 1989, the British COMA report on food policy the same year, and others. I could have also mentioned the 1984 NIH consensus conference on “lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease” that followed on this legendary Time Magazine cover – “Cholesterol, And Now the Bad News” – and the founding in 1986 of the National Cholesterol Education Program, which published its guidelines for cholesterol lowering the following year. All focused on dietary fat and serum cholesterol as the agents of heart disease and all mostly or completely ignored the evolving science on insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome that implicated sugar and other processed carbohydrates.

Indeed, if anything, the more relevant of the two USDA Dietary Guidelines, the one that Dr. Guyenet does not address, is the 1985 version that declared without a caveat, as I noted, that “too much sugar in your diet does not cause diabetes.” This is, of course, remains the critical question and the one that yet has to be rigorously tested (ignoring the tautology implied by the use of the words “too much”).

Dr. Guyenet, Dr. Freedhoff, and I all agree that had Americans eaten as the guidelines cautioned (and just as Michael Pollan would have preferred as well), we’d all very likely be healthier. But we didn’t. The question is whether the dietary fat/serum cholesterol/heart disease obsession directed attention away from the hypothesis that sugar causes heart disease, diabetes, and perhaps obesity as well through its effect on insulin resistance. The secondary question is whether this obsession in government documents, programs, journalistic coverage, and (pseudo)scientific reviews explains why we continued to eat such high sugar diets. As Dr. Guyenet notes, Americans still consume a significant amount of our calories from grain-based desserts and sugary beverages. But why? By focusing on the straw man of the 1980 guidelines, Dr. Guyenet fails to address that question. That he’s taking on a straw man makes me thinks he’s more interested in appearing to win an argument than in dealing with what may be the single most important public health issue of our era.

A key point to make, as Professor Kealey does, is that Americans did indeed respond to the dietary dogma of the 1970s and 1980s by changing their diets. Dr. Freedhoff and Dr. Guyenet are wrong in this regard when they attend only to the total percentage and amounts of fats, carbohydrates, and protein in our diets, and not the type of fats, carbohydrates, and even protein. Looking at what we ate instead of how much we ate supports the supposition that Americans heard the advice on fat and acted on it, even as we were ignoring the sugar advice. As the USDA reports, between 1970 and 2005, we cut down on our use of butter (-17%) and lard (-66%), while almost doubling vegetable oil consumption (from 38.5 pounds per capita yearly to 73.7); we more than doubled how much chicken we ate (33.8 pounds per capita yearly to 73.6, probably skinless white meat, but I’m speculating), while reducing our red meat consumption by 17 percent, and beef by 22 percent. We cut back on eggs, too. So while total fat consumption decreased only marginally, as Drs. Freedhoff and Guyenet note, that marginal decrease is accompanied by a reduction in animal fats and their replacement by vegetable oils, which were thought to be heart healthy and still are (perhaps also erroneously). The type of fats we consumed and the type of foods we consumed changed significantly, and this change was very much in accord with what we were being told.

The post-1980 focus on dietary fat also led to the creation and sale of thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of non-fat and low-fat food-like substances (credit for the terminology once again to Mr. Pollan). In this instance, the CDC’s publication Healthy People 2000 is informative: Healthy People 2000 included multiple “nutrition objectives” aimed at reducing dietary fat consumption, including the creation of 5,000 low-fat or low-saturated fat products. It included nutrition objectives to reduce salt intake and increase complex carbohydrate and fiber consumption, but included no such objective for sugar or sugar-rich foods. Why not? Indeed, I find that the words “sugar” or “sugars” appear only five times in the almost 400-page final review of how well the guidelines were met. In 1995, the American Heart Association counseled in one of its pamphlets that Americans could control the amount and kind of fat consumed by “choos[ing] snacks from other food groups such as…..low-fat cookies, low-fat crackers,…unsalted pretzels, hard candy, gum drops, sugar, syrup, honey, jam, jelly, marmalade (as spreads).” In 2000, the AHA published this cookbook of low-fat and luscious sugar-rich “soul-satisfying” desserts. I don’t know if Dr. Guyenet would describe this as a “weak stand” on sugar or not, but it does shed light on our failure to limit sugar consumption during a period in which all public health advice was focused on reducing fat.

The more important question, and a very different one, is whether our sugar consumption has uniquely deleterious effects on our health. To refute the claim that consuming sugar might cause heart disease, Dr. Guyenet points out that heart disease mortality has dropped precipitously over the years of the obesity and diabetes epidemics and during a period when sugar consumption clearly increased (technically “caloric sweeteners” since the increase was due primarily to high-fructose corn syrup). Professor Kealey makes a similar point but with a far more nuanced perspective about how mortality rates are confounded by what are, after all, a half-century’s worth of very concerted efforts by medical researchers, the pharmaceutical and medical industry, and public health authorities to reduce mortality. That these efforts succeeded in reducing mortality is indeed commendable, but it makes it far more difficult than Dr. Guyenet suggests to derive meaning from the mortality data. If it’s evidence against the sugar hypothesis, it’s very weak evidence.

Dr. Guyenet references a 2007 article that applies a statistical model to assign proportions of the declining mortality to a variety of causal factors. Aside from the usual problem with models (all are wrong, some are useful, as the statistician George Box famously put it) the authors note that even in the model they employed, the declines in mortality that they observed “were partially offset by increases in the body-mass index and the prevalence of diabetes.” This would be expected if sugar consumption is a causal factor in obesity and diabetes, as proposed in my books. Hence I fail to see how this evidence would hold up in any court, science or law, as a reason to exonerate sugar.

Professor Kealey’s reference – a 2013 statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association – is far more skeptical, and rightly so, about what can and cannot be concluded from the mortality data. It says, regarding the decrease in stroke mortality, all of which would be relevant to heart disease mortality as well:

These significant improvements in stroke outcomes are concurrent with cardiovascular risk factor control interventions. Although it is difficult to calculate specific attributable risk estimates, efforts in hypertension control initiated in the 1970s appear to have had the most substantial influence on the accelerated decline in stroke mortality. Although implemented later, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia control and smoking cessation programs, particularly in combination with treatment of hypertension, also appear to have contributed to the decline in stroke mortality. The potential effects of telemedicine and stroke systems of care appear to be strong but have not been in place long enough to indicate their influence on the decline. Other factors had probable effects, but additional studies are needed to determine their contributions.

Even Dr. Guyenet’s 2014 reference – “Challenges of Ascertaining National Trends in the Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in the United States” – concludes with a statement that is difficult to reconcile with his confidence that this evidence tells us anything meaningful about the hypothesis that sugar is a cause of insulin resistance and so heart disease. The studies discussed, the authors write in the last two sentences, “yield encouraging but tentative signals that the incidence of CHD in the United States may be waning. Bringing greater clarity to this important topic of cardiovascular epidemiology poses a pressing public health need.”

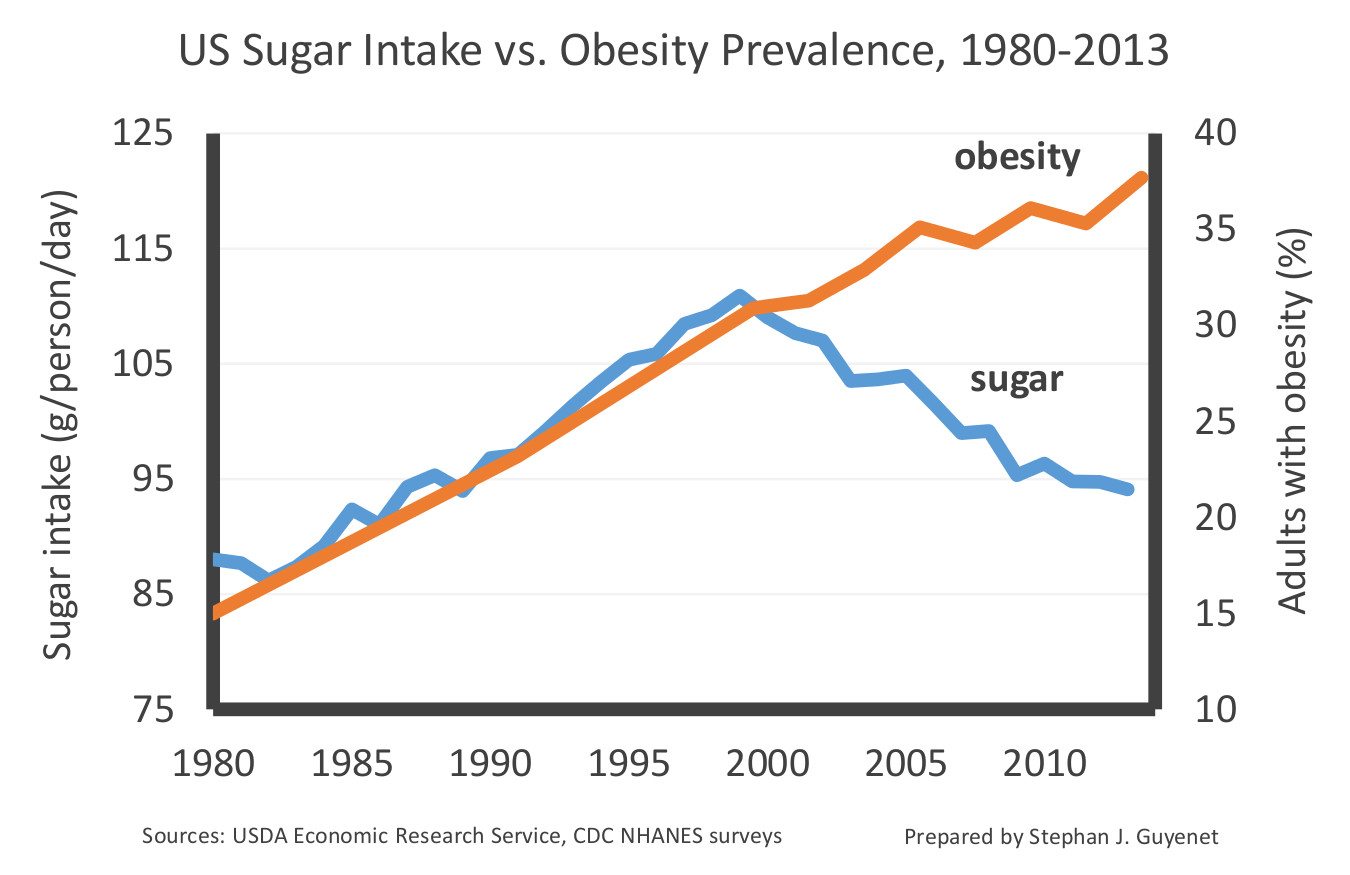

In Dr. Guyenet’s commentary, he concludes with what he considers strong evidence to refute the hypothesis that sugar consumption is a unique cause of obesity and so, by association, diabetes. It is, he says, the results of an experiment in which an entire nation cuts its sugar consumption with the outcome of interest being the national prevalence of obesity. Here’s Dr. Guyenet’s evidence:

Considering the diverging trends in this chart post-1999, Dr. Guyenet writes, “Americans have been reining in our sugar intake for more than fourteen years, and not only has it failed to slim us down, it hasn’t even stopped us from gaining additional weight.”

A minor point is that Dr. Guyanet’s chart is deceptive. Dr. Guyenet inflates the sugar intake scale, such that a modest 15 percent decline in relative sugar intake is comparable in scale to what would be a dramatic forty percent decline in the relative prevalence of obesity. In doing so, he makes the reining in of sugar consumption since 1999 look more dramatic than it might otherwise look. Had he kept the scales more equitable, we could have imagined why a modest drop of 15 percent in sugar consumption might do little to stem the tide in obesity.

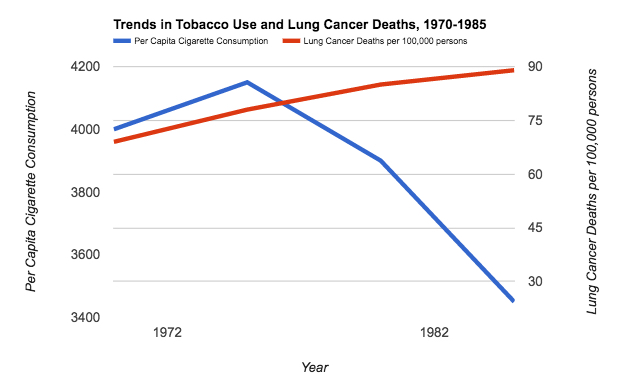

To help understand why not, let’s imagine a similar situation with cigarettes and lung cancer. Would we expect a 15 percent decline in cigarettes smoked per capita – say from 20 cigarettes a day to 17 – to lead to an immediate decline in lung cancer incidence or even to a stemming of the tide? And would Dr. Guyanet then conclude: “this suggests that cigarette smoking is highly unlikely to be the primary cause of lung cancer in the United States?” I’m going to go out on a limb here and say I kind of doubt it.

We can use a similar chart from the lung cancer/cigarette experience to further demonstrate the problem with Dr. Guyenet’s simplistic assumption that every cause has to be promptly and linearly associated with its effect. Here’s a chart, courtesy of the CDC, showing per capita cigarette consumption in the U.S. – which peaked in 1965, the year after the Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health – and per capita lung cancer rates, which took thirty years to turn over and head downward.

And here’s a part of that chart blown up, using Dr. Guyenet’s color scheme, to make what Dr. Guyenet would seemingly argue is a case against cigarettes as a primary cause of lung cancer.

It would indeed be nice if our bodies, both on a population-wide and individual basis, responded immediately to the removal of a toxic substance from the environment. But there are many reasons why they wouldn’t, among them being threshold effects, intergenerational effects (the passing down of a predisposition to become obese and diabetic from mother to child in the womb, as documented in the Pima population and discussed in my books) and an incubation period for development of the disease, of the kind that explains the smoking and lung cancer delay. As I noted in my 2007 book, Good Calories, Bad Calories, after studying the diabetes epidemics among local ethnic groups in the 1950s, the South African diabetologist Dr. George Campbell suggested both a 20-year gestation period (similar to lung cancer), and increasing rates of diabetes in populations so long as consumption was above a 70 pounds per capita per year threshold.

Considering both the American Heart Association and the World Health Organization now suggest that a healthy diet should contain no more than about 50 pounds of sugar yearly, and ideally half that, and consider we’re still at a population level well above 70 pounds, it’s a safe bet that we wouldn’t expect a downturn in obesity quite yet from the data Dr. Guyenet provides.

It’s this kind of simplistic argument and a lack of understanding of the very obvious limitations of observational and epidemiological data that I have argued in my books got us into this dire public health situation. What we all need are more informed and nuanced and, yes, skeptical discussions of what the evidence can and cannot establish to get out of it.

Dr. Freedhoff takes a different tack, suggesting not that I’m simply wrong, as Dr. Guyenet does, but that I’m missing a point that is all too clear to a working physician. When he notes that there were flaws in the science of the case against dietary fat, and that such flaws are also present in the sugar data, he is echoing the points I make in my book on sugar. That I am nervous about government regulation of sugar and sugary products is at least partly for this reason.

Dr. Freedhoff is right that I believe that the only way to stop an epidemic is to first unambiguously identify the cause, and my book and this article are about the possibility that sugar is it. I do not believe “ultraprocessed” foods are responsible or even a meaningful way to identify what is the cause. Certainly not, if they’re defined as “ready to consume (or heat) formulations manufactured from cheap ingredients.” If we go looking for them, which is always a good idea, we can find epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the literature in populations going back more than a century, in which such ready to consume formulations did not exist. What these populations had, though, was sugar, white flour, and maybe alcohol, and these were new additions to their diets. It’s possible that because my training is in physics and Dr. Freedhoff’s is in medicine that we just assign a different value to the usefulness of Occam’s razor in establishing reliable knowledge. I believe these historical populations, enumerated in my second book, Why We Get Fat, can be used to rule out suspected causes including ultraprocessed food, however that’s defined. Dr. Freedhoff finds them less valuable, and we have discussed this in the past.

Dr. Freedhoff is concerned with the advice he should give his patients to maximize their health, which includes maximizing their happiness. I’m concerned with identifying the causes of the epidemics such that we know what has to be done to stop them. If sugar is the ultimate cause of obesity and diabetes, however, which is at least a viable hypothesis, then I can’t agree with Dr. Freedhoff that his advice to his obese and diabetic patients should not include making this fact abundantly clear.

This is why I often evoke cigarettes as a comparison. Because, based on solid evidence, we are confident that smoking causes lung cancer, we do not advise smokers to smoke in moderation or to worry that non-smoking will make them unhappy. (It certainly will, at least in the short run. I can personally vouch for that.) We don’t assume that if we tell them that cigarettes cause lung cancer, this will reduce the likelihood that they’ll quit, because changing their behavior for their own good may be an unrealistic luxury for them. We give them the knowledge and we let them decide. We don’t say, “what’s the smallest amount needed to be happy?” as Dr. Freedhoff suggests about dietary indulgences. We counsel, as Dr. Freedhoff also does, “not smoking.”

While Dr. Freedhoff’s seven behaviors may make for a happier life, they may direct the attention of his patients away from precisely those behaviors (i.e., eating of certain foods) that triggered their condition. Moreover, his claim that the behaviors he does advise will bestow “incredible health benefits” is as bereft of science as his worries about targeting sugar. I doubt we need clinical trials to suggest we’ll be healthier and happier if we get a good night’s sleep and nurture our relationships, but to assume that obese and diabetic people don’t, and to make this the basis of treatment for people who come to Dr. Freedhoff to be helped, seems condescending. We have our mothers and our friends to give us that advice. What we need our doctors to tell us (correctly) is why we got fat, and why we got diabetes, and what we can do to reverse it. And then it will be up to us to decide if we want to follow that advice.

Finally, I would like to thank Professor Kealey for the kind words and his thoughtful assessment. I would take issue with one statement, which is whether or not I am the most influential journalist in the nutrition area. I would have voted for Michael Pollan in that regard, although it is possible that he might vote for me. In doing so, as he did in a recent article, he might leave it ambiguous whether my contribution is ultimately to the benefit of our health, or the harm.