I have very thankful to Michael Teter, Clint Bolick, and John O. McGinnis for their comments. I appreciate them taking the time to write about the confirmation process.

Response to John O. McGinnis.

I am in strong agreement with almost everything John McGinnis wrote. As he said, eliminating filibusters will make confirmations easier, but it is important to note that change comes at a cost. Requiring that members of both parties support confirming a judge stops the most extreme nominees from getting through, which is a good thing.

Also not discussed are the medium term effects. Democrats disproportionately gained from ending the filibuster because they get to fill all the nominations they blocked at the end of the Bush administration. Since Democrats fought somewhat harder against the brightest Republican nominees than vice a versa, only analyzing the number of seats on the courts understates Democrats’ domination of the federal courts.

Responses to Michael Teter.

1) “Only 56 percent of President Obama’s district court nominees were confirmed during his first two years – when Senate Democrats held 59 or 60 seats.”

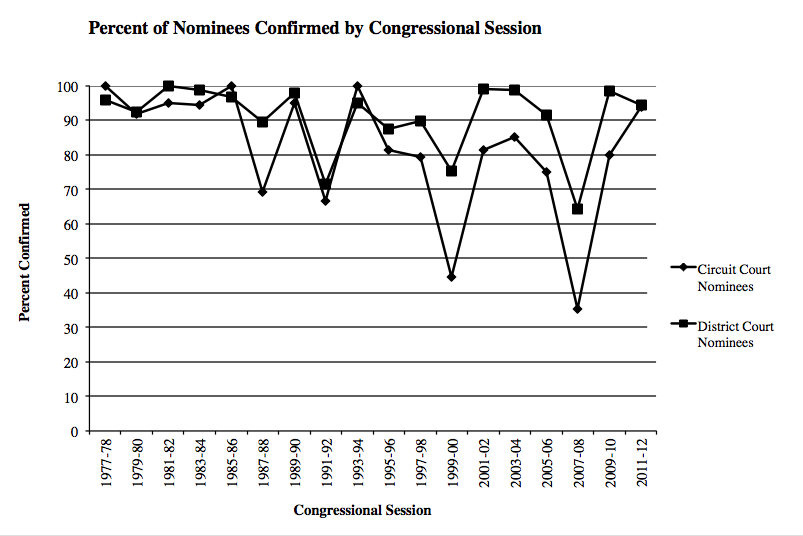

This is a true but an extremely misleading claim. Considering all the judicial nominations made during President Obama’s first two years, 98 percent of his District court nominations and 80 percent of his Circuit court nominations were eventually confirmed. Many of Obama’s nominees simply had to wait until the next congress before their confirmations. And it had nothing to do with party politics. There were two simple reasons: Obama was notoriously late during the congressional term in nominating judges, and the Senate confirmation process for lower court judges was put on hold when two Supreme court nominations were being considered during 2009.

For example, during Obama’s first two years in office, five of Obama’s twenty-five nominees for the circuit court weren’t announced until just five months before the November mid-term elections, a time when it is normally almost impossible for nominations to be considered. In contrast, George W. Bush was much quicker making nominations, with very few (only one out of thirty-two) circuit court nominations that close to his first mid-term election.

Virtually all of President Obama’s first-term district court nominees were confirmed, and the district and circuit court nominations made during his first term have enjoyed the highest confirmation rates since Reagan.

2) “[T]he judicial vacancy rate has actually increased during President Obama’s time in office, whereas George W. Bush saw a 40 percent decrease in the vacancy rate during his eight years.”

Mr. Teter’s claim that this is due to “delays and obstruction” in the Senate is not supported by the facts. Even many liberal groups have remarked on the slow rate Obama nominated judges. The Brookings Institution noted: “President Obama’s first term saw comparatively fewer nominations, submitted relatively later, with greater times from district vacancy to nomination and confirmation, and an increase in vacant judgeships.” (http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2012/12/13-judicial-nominations-wheeler) The greater lengths noted from vacancy to confirmation were entirely driven by the increase in the length from vacancy to nomination. Thus, again, those delays were not the fault of the Senate nor of Republicans.

3) “While it is true, therefore, that the process for confirming judges has become more politicized as judges decide more political questions, there is little to support—and much to contradict—tying the broken system to the size of the federal government. The real cause of the problem resides in the Senate’s institutional rules and norms, along with the electoral incentives pushing senators to delay and obstruct judicial candidates nominated by the president of an opposing party. This latter point is well documented. As other noted scholars have observed, ‘Both parties…have made the plight of potential judges central to their campaigns for the White House and Congress.’”

When more is at stake, economic theory predicts that people will fight more to win the contest. This doesn’t just go for judicial confirmations. Just as with the increasingly difficult confirmations, many also complain about the increase in campaign expenditures. But do people think that campaign contributions would be anywhere near as large as they are today if the federal government still constituted only about 2 to 3 percent of GDP, like it did a century ago? Indeed, up to about 80 percent of the growth in state campaign expenditures can be explained simply by the growth in state governments. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=245336

Despite Teter’s insistence, changes in the Senate’s institutional rules over the last five decades can’t explain the changes in the length of the confirmation process. Senators have made greater use of existing rules to stop confirmations because more has been at stake in who becomes a judge.

The fact that both political parties have complained about the difficulty in confirming judges is perfectly consistent with my theory. As more is at stake with the ever growing power of the federal government and the federal courts and judges feel less constrained by the black letter law, it becomes more important which party gets to put its judges on the courts.

Teter seems to deny both that the creation and growth of federal regulatory agencies has largely driven the 12-fold increase in per capita circuit court cases since the early 1960s and that growth has increased the importance of who is a judge. But without that regulatory growth, we wouldn’t have federal court battles over whether carbon dioxide is a pollutant. Many of the other cases that I listed in my piece were similar. In addition, judges’ political views allow them to intervene in “gay marriage, affirmative action, criminal procedural rights, the death penalty” in ways that federal judges wouldn’t have dreamed about prior to the 1960s.