Mr. Lott’s suggestion – shrink the size of the federal government to address the broken judicial confirmation process – is an ideologically driven solution to a non-ideological problem… . Those who have lost the debate about the size of the federal government are retreating to the judiciary, in hopes that activist conservative judges will undo what the democratic branches have done.

My statements were purely positive, not ideological. I have not argued that reducing the size of government is likely. Indeed, my book, Dumbing Down the Courts, acknowledges that this is extremely unlikely. Nor can Mr. Teter point to one single place in my book or my original essay where I have said that shrinking the size of government is “good.”

My point was simple: if one wants to understand how we got where we are or to predict how things will be changing in the future, it is important to understand what is causing the increased confrontations in confirmations. With the continued growth of government, as Clint Bolick correctly notes in his response, the pressures that existed behind these confirmation battles will continue to grow. Pointing out that simple prediction is not ideological.

What can be said about the size of government can also be said about the willingness of judges to let their own political views determine their judicial decisions. Most who desire a “living constitution” undoubtedly also support a larger, more powerful federal government. If that is what Mr. Teter wants, fine, that isn’t my debate here. But everything else equal, there is a cost to judges interpreting the constitution or laws according to their own beliefs: a more divisive judicial confirmations.

Ironically, Mr. Teter is concerned about more “activist conservative judges,” but at the same time he advocates gutting the filibuster rules that have helped ensure that more moderate judges are confirmed.

The answer [for the broken nomination process] … is the abuse of Senate rules and norms.

The problem with Mr. Teter’s answer is that it doesn’t explain why the rules are being abused now more than previously. My answer and the evidence present in my book indicates that the reason Senators have been more willing to bend the rules is that more is at stake over who gets to be a judge than was true 40 or 50 years ago. Mr. Teter’s answer provides a description if how the process is breaking down, not why it is breaking down. He is looking at the symptoms, not the causes.

Mr. Lott ignores: why nominate someone who we know is going to get blocked? Moreover, part of the delay is due to the fact that President Obama took the Senate’s ‘advise’ role more seriously than his predecessors and many senators exploited that opportunity to delay the nomination process.

Sorry, but this is completely inaccurate. My book, discussed here, Dumbing Down the Courts, provides very extensive discussions on these issues. For example, I point out that the simple lower confirmation rates and longer confirmations underestimate the true deterioration in the process. Judges, such as Richard Posner, Frank Easterbrook, and J. Harvie Wilkinson (the most influential circuit court judges), who made it through their confirmations during the 1980s, would be very unlikely to get through today. But since similar nominees today understand this, many fewer are willing to have their names put into nomination. Presidents also understand this, and they are likely to compromise on whom they nominate.

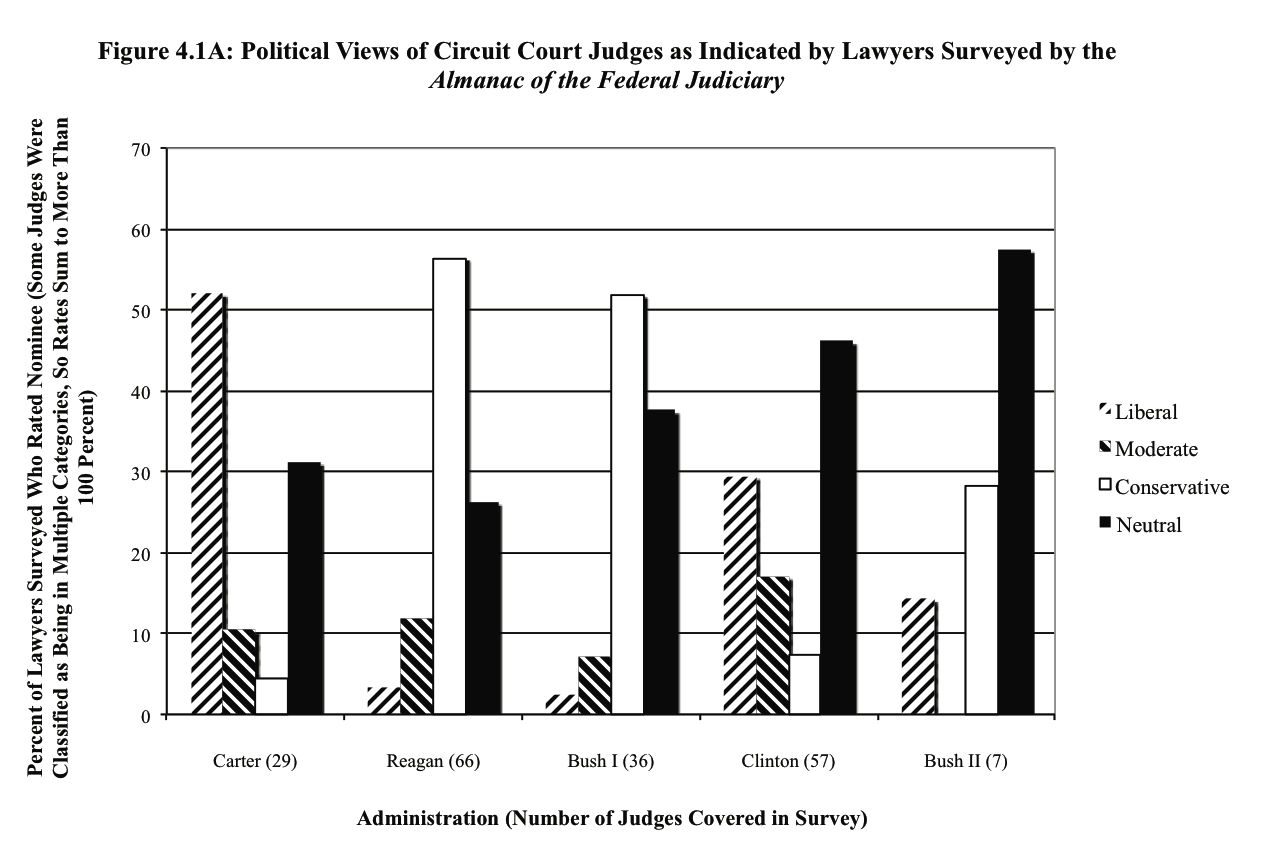

The regression estimates in my book take into account everything from the president’s approval rating, whether the president’s party controls the senate and other information on the confirmation process, what the nominee has published and where, and extensive information on the nominee and his background. One finding is that nominees don’t seem to be having more difficult confirmations because presidents have been nominating more ideological nominees. In fact, according to surveys of lawyers who practice before these judges by the Almanac of the Federal Judiciary, at least through George W. Bush, these practicing lawyers view the judges confirmed by more recent presidents as being much less likely to let their political views influence their judicial opinions.

I am unaware of any empirical evidence that President Obama has been more careful in whom he has nominated to the courts, nor is there any evidence that explains the much longer delays in nominations. I was unable find evidence of that increased carefulness in terms of readily observable factors such as where nominees went to law school, how well that they did in law school, clerkships, publications, or anything else.